Legal Analysis: Rasmea Odeh’s “expert” PTSD testimony inadmissible under clear court standards

Novel theory of “filtering” not recognized in medicine or law.

Rasmea Odeh is the terrorist member of the military wing of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine who was convicted in Israel in 1970 of the 1969 bombing of the SuperSol supermarket in Jerusalem that killed two Hebrew University students, Edward Joffe and Leon Kanner. Rasmea also was convicted of the attempted bombing of the British Consulate.

Rasmea was released in 1979 in a prisoner exchange for an Israeli soldier captured in Lebanon.

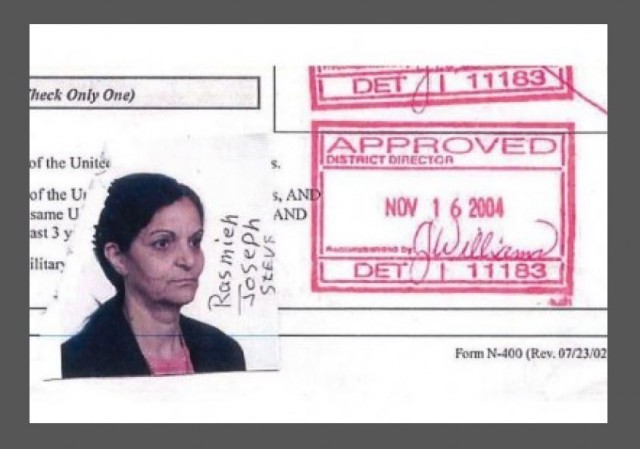

Rasmea made her way to the U.S. in the mid-1990s, where she lied on her visa application by denying any prior convictions or imprisonment, and again in her 2003 naturalization application when she repeated the same false answer. For more background, and how Rasmea’s supporters have distorted history, see Rasmea Odeh rightly convicted of Israeli supermarket bombing and U.S. immigration fraud and Rasmea Odeh’s victims – then and now.

Rasmea was convicted of immigration fraud in federal court in Detroit in November 2014, sentenced to 18 months in prison and ordered deported after release from prison.

Rasmea has become a hero to the anti-Israel movement in the U.S., which falsely claims she confessed to the supermarket bombing only after 25 days of horrific sexual torture. In fact, the records show she confessed the day after arrest, there was substantial corroborating evidence, and she received a trial that an observer from the International Red Cross termed fair. Rasmea’s main co-conspirator has said in a video interview decades later that Rasmea was the mastermind.

Novel Theory of PTSD “Filtering”

The Court of Appeals sent the case back to the trial court (but did not reverse the jury conviction) to hold a hearing as to whether Rasmea should have been permitted to call a PTSD expert to testify in the original trial to bolster Rasmea’s claim that she did not knowingly lie. The Appeals Court did NOT rule that the testimony should be admitted, rather that the trial court should have held a hearing. So, the Appeals Court ordered the trial court to hold a hearing under normal standards for qualifying and presenting expert testimony in federal court.

If the trial court rules that the PTSD filtering defense does not meet the scientific and legal standards required for such testimony, then the conviction stands. If the trial court rules the expert testimony is admissible, then there will be a new trial in January 2017.

That PTSD defense is highly unusual because Rasmea does not claim she blocked out memory of her conviction and imprisonment. Indeed, her hearing testimony demonstrated that she did NOT block out the memory. From the government’s appeal brief:

The flaw in Odeh’s argument is that as she posits it, the expert testimony would have contradicted, not supported her trial testimony. At trial, Odeh testified that she was fully aware of her criminal history, and that upon analyzing the form, concluded in good faith that it did not request information about events other than in the United States.

Thus, when asked on direct examination why she had answered “No” to the criminal history questions on the naturalization application, Odeh testified that after reading previous questions, such as “Have you ever claimed to be U.S. Citizen in writing or any other way,” and “Have you ever registered to vote in any federal, state, or local election in the United States,” she consciously and rationally concluded that all the questions must refer to the United States. (R. 182: Tr., 2365–66). “When I continue the other questions, my understanding was about United States. So I continue to say, no, no, no.” (Id. at 2366).3 Odeh continued her direct testimony by answering the question, “when you were filling out that form and they asked you were you ever in prison or convicted or arrested, did you ever, did you think at all about what had happened to you in Israel in 1969 and 1970?” Odeh answered, “Never I thought

about Israel. My understanding was about United States, and I believe if, if I knew that about Israel, I will say the truth.” (Id. at 2367).When her attorney asked Odeh, “Is it your testimony that if you thought the questions referred to what happened to you in Israel, you would have answered those questions and given the information to the INS,” she replied “Yes. I will give them. Yes.” (Id.). To the question of “So is it your testimony that if you interpreted the question or understood the question to talk about what happened to you in Israel, you would have answered the question, yes, and given the information to the immigration [sic],” Odeh replied “Yes, if I understand that, of course.” (Id. at 2368)….

Since Rasmea cannot claim that PTSD caused her to block out the memory of her conviction and imprisonment, Rasmea has come up with a novel theory. Through her proposed expert, Dr. Mary Fabri, Rasmea claims that her trauma caused her to filter the question of whether she “EVER” (caps and bold on original naturalization form) had been convicted or imprisoned, in such as way as to answer incorrectly despite that fact that Rasmea had not blocked out the memory.

The court will hold the hearing on the PTSD expert on November 29, 2016. In advance of the hearing, the Court ordered Rasmea to undergo a mental examination by a prosecution expert. The prosecution and defense are to submit legal briefs by November 15, 2016.

No Medical or Case Law Support for Novel “Filtering” Theory

Because this case has been of interest to me, and I’ve met the siblings of Edward and Leon and visited the graves of Edward and Leon, I decided to take a look at the law of expert witnesses.

![[Sisters of Leon Kanner, brother of Edward Joffe[[Photo by William Jacobson, May 2015, Israel]](https://c2.legalinsurrection.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Irit-Kanner-Miriam-Kanner-Harold-Joffe-Rachel-Kanner.jpg)

[Sisters of Leon Kanner, brother of Edward Joffe][Photo by William Jacobson, May 2015, Israel]

The legal analysis below is by the former student, though I did some editing for presentation in a blog format, as well as to add some context about the case.

The issue is fairly straightforward. In order to present expert testimony, one has to meet standards of reliability and scientific support. One cannot invent science for the purpose of a case — the expert has to rely on pre-existing reliable science. All of the case law emanates from the U.S. Supreme Court case, Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, 509 U.S. 579 (1993)

Here, however, none of the affidavits submitted by the defense cite any scientific study or authority for this peculiar “filtering” theory. Certainly, PTSD from torture is recognized, but the defense has not submitted any medical authority for the filtering theory that would cause a person to misunderstand a question and to answer it falsely despite remembering the traumatic event (as opposed to completely blocking out a memory or other reaction).

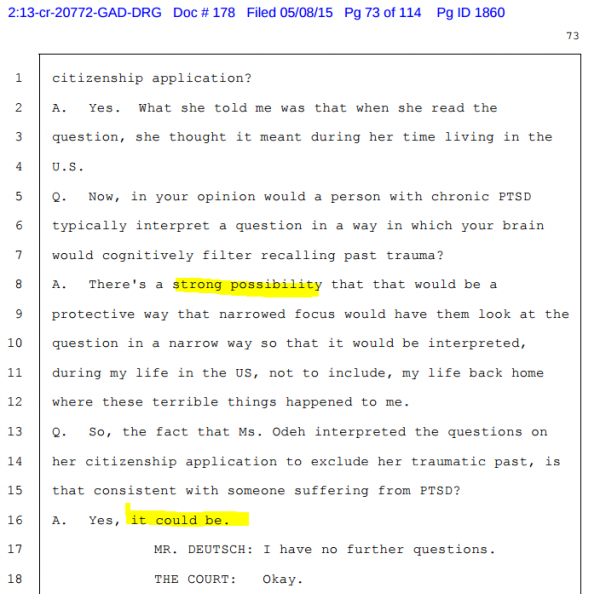

Moreover, Rasmea’s expert’s testimony is completely speculative; Dr. Fabri asserts that there was a “strong possibility” that PTSD contributed to the way Rasmea answered the questions, but Dr. Fabri does not say that the filtering caused the false answers.

Not surprisingly, no court has recognized the filtering theory asserted here. Here are the cases setting forth the standards showing why the lack of scientific and legal authority should result in exclusion of the testimony:

1. First, “[t]he proponent of the expert testimony must prove by a preponderance of the evidence that the testimony is reliable.” Lassiegne v. Taco Bell Corp., 202 F. Supp. 2d 512, 515 (E.D. La. 2002) (quoting Tanner v. Westbrook, 174 F.3d 542, 547 (5th Cir. 1999)). “The aim is to exclude expert testimony based merely on subjective belief or unsupported speculation.” Id.

2. There has never been a court case where a psychological expert has ever opined that a person with PTSD answered a question incorrectly because they were trying to avoid a traumatic experience. There certainly has never been a case where an expert testified that someone who had PTSD answered a question wrong when the PTSD was not activated.

3. PTSD is a well-known and valid item that may be discussed by an expert. “We hold that PTSD testimony is grounded in valid scientific principle.” Isely v. Capuchin Province, 877 F. Supp. 1055, 1062 ( E.D. Mich. 1995) (quoting State v. Alberico, 861 P.2d 192, 208 (N.M. 1993)).

4. An expert must show the court that others have used, tested, measured, and accepted the proffered theory before. “[T]he proffered expert must be able to assure the Court that his/her theories have some degree of scientific validity and reliability. In particular, the witness should testify as to whether that theory can be, or has been, tested or corroborated and, if so, by whom and under what circumstances; whether the theory has been proven out or not proven out under clinical tests or some other accepted procedure for bearing it out; and whether the theory has been subjected to other types of peer review.” Id. at 1064. Stated differently, the Iseley court held that:

Under the Daubert guidelines, the trial court should determine:

(1) Whether the theory in question can be or has been tested;

(2) Whether the theory has been subjected to peer review and publication;

(3) The known or potential rate of error; and

(4) Whether there has been widespread acceptance of the theory in the relevant scientific community.

Id. at 1058 (citing Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 509 U.S. 579, 593-94 (1993)).

Obviously, Odeh has done none of these things. She nowhere discusses where this “incorrect question answering by one with PTSD when the PTSD is not activated” theory has ever been (i) tested, (ii) subjected to peer review and publication, (iii) measured for a known error rate, or (iv) whether this theory has any acceptance, never mind widespread acceptance, in the relevant scientific community. Her opinion is just that, a bare opinion with no support whatsoever. That is improper and should not be allowed by the court. See also General Electric Co. v. Joiner, 522 U.S. 136, 146 (1997) (“[N]othing in either Daubert or the Federal Rules of Evidence requires a district court to admit opinion evidence which is connected to existing data only by the ipse dixit [i.e. the mere say-so] of the expert”).

5. In Isely, the court allowed the expert to testify as to repressed memories (i.e. a complete blackout of prior memories). The plaintiff in that cased argued that because he had completely blocked out memories of the abuse that caused his PTSD, the statute of limitations for bringing the abuse claims had been tolled. “Dr. Hartman testified that there is a fair degree of acceptance of the concept of repressed memory in the field. She opined that the majority of clinicians accept the concept. However, she noted that, although is a diagnostic category in both the DSM III- and the DSM IV-R, repressed memory is not. She also acknowledged that there are detractors who do not accept the theory. One of those major detractors, Elizabeth Loftus, of the University of Washington, conducted studies on eyewitness identification. However, Loftus’s work has been countered by others in the field. So, although the concept of repressed memory has gained some adherents in the field of psychology, that acceptance is not universal. . . . Based upon the foregoing foundational testimony, the Court finds that Dr. Hartman has met the foundational requirements to testify regarding PTSD and repressed memory.” Isely, 877 F. Supp. at 1065-66. The court also noted that in one study, 40% of adults who had been abused as children did not remember at least part of the abuse. But, of course, as mentioned, no one has ever discussed this as a way of causing one to make a mistake on a form when not suffering a PTSD attack.

6. In State v. Quattrocchi, 1999 R.I. Super. LEXIS 129 (R.I. Super. Ct. Apr. 28, 1999), the court held that a state expert’s opinion that consisted of a theory that an alleged victim of sexual assault could have suppressed memories of the assault and then “recovered” them was inadmissible. Specifically, the court held that the court held that (i) the theory had not been tested, (ii) while there had been peer reviewed studies of the theory, continuing debate over its validity existed, (iii) there was “no quantifiable error rate regarding ‘false’ repressed and recovered memories,” and (iv) there was not general acceptance of this theory. In sum, the court held, after a lengthy hearing, that “expert testimony relating to the basis for such repressed recollection is unreliable and, therefore, inadmissible.” Id. at *32-46.

7. In State v. McDonald, 718 A.2d 195 (Me. 1998), the Supreme Court of Maine affirmed a trial court’s exclusion of an expert who claimed that the defendant arsonist “suffered from a form of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) he called ‘adult children of alcoholics syndrome,” which caused the defendant to make a false confession. In affirming the Court stated that the expert:

acknowledged that his adult children of alcoholics syndrome diagnosis was not recognized by the definitive treatise on psychological diagnoses, the DSM-IV. Further, his proffered opinion concerning the likelihood of false confessions was, by his own admission, based only on his empirical observations. He acknowledged both the complete lack of published studies by other mental health professionals supporting his false confession hypothesis and the fact that he had not conducted any studies on the subject.

Id. at 198. Because of this, the Court held:

[a]lthough the lack of published studies is not a dispositive consideration when assessing the validity of a proffered scientific theory, it is a relevant consideration. The Daubert Court stated, ‘Submission to the scrutiny of the scientific community is a component of ‘good science,’ in part because it increases the likelihood that substantive flaws in methodology will be detected.’ Thus, the court could reasonably have concluded that [the expert’s] proffered testimony had little value as scientific knowledge because, having not been derived through the methods and procedures of science nor subjected to peer review, it amounted to little more than [the expert’s] subjective opinion.”

Id. See also Chapman v. Maytag Corp., 297 F.3d 682, 687-688 (7th Cir. 2002)):

A very significant Daubert factor is whether the proffered scientific theory has been subjected to the scientific method. It is undisputed that Petry did not conduct any scientific tests or experiments in order to arrive at his conclusions. Petry never produced any studies, tests or experiments to justify or verify his conclusions, despite his representations to the court that such test results would be forthcoming. In our opinion, the absence of any testing indicates that Petry’s proffered opinions cannot fairly be characterized as scientific knowledge. Personal observation is not a substitute for scientific methodology and is insufficient to satisfy Daubert’s most significant guidepost. Petry’s opinions amount to nothing more than unverified statements unsupported by scientific methodology. Accordingly, the district court erred when it did not exclude Petry’s testimony.

8. Fabri’s expert report also does not support her testimony. The expert report says that “someone with PTSD would cognitively process questions about the past to avoid recalling traumatic experiences, such as torture, that are at the root of one’s disorder.” Report at 16. But in her testimony, she opines that “Either it’s effective [i.e. the filters are stopping you from remembering things] and it’s working and the focus is narrowed, or you’re activated, you’re aroused, you’re having many symptoms and your filters are off.” Evidentiary Hearing Transcript at 101. That is not what her expert report says. That is fatal to admissibility.

See Nolan v. United States, 2015 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 115807, at *17-18 (N.D. Ill. Sept. 1, 2015):

Dr. Reff did not properly disclose his breach opinions concerning psychotherapy and private consultation in his October 2013 expert report under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 26(a)(2), which requires that an expert must disclose a ‘complete statement of all opinions [he] will express and the basis and reasons for them.’ See Novak v. Board of Trs. of So. Ill. Univ., 777 F.3d 966, 972 (7th Cir. 2015). ‘Failure to comply with the disclosure requirements of Rule 26(a) results in automatic and mandatory exclusion … ‘unless the failure was substantially justified or is harmless.’’ Id. (quoting Fed. R. Civ. P. 37(c)(1)); see also Rossi v. City of Chicago, 790 F.3d 729, 738 (7th Cir. 2015). With less than two weeks until trial, the prejudice against Defendant in failing to disclose these opinions and their bases is insurmountable. See Tribble v. Evangelides, 670 F.3d 753, 760 (7th Cir. 2012); David v. Caterpillar, Inc., 324 F.3d 851, 857 (7th Cir. 2003). Moreover, there is nothing in the record indicating that Dr. Reff’s failure to disclose these opinions is substantially justified. See Rossi, 790 F.3d at 738; Novak, 777 F.3d at 972. Therefore, Nolan cannot rely on these non-disclosed opinions in relation to Drs. Dana’s and Harvey’s breach of the standard of care.

Amicus Brief by Groups Supporting Rasmea do not show any legal authority for the filtering theory

The following cases are cited in in an Amicus Brief submitted in the Appeals Court in support of Rasmea by several groups that lend assistance to survivors of torture. No case is cited, however, for this filtering theory.

Tun v. Gonzales, 485 F.3d 1014 (8th Cir. 2007). Cited for the proposition that “U.S. courts and administrative bodies routinely use expert witness testimony on the psychological impact of torture in cases involving torture victims.” Tun did reverse an immigration judge’s ruling that a doctor could not testify about whether the petitioner’s physical scars and PTSD were consistent with being tortured. The issue of filling out a form incorrectly is not addressed by Tun, although the expert would have testified that the victim’s PTSD symptoms included memory loss and “difficulty sleeping, nightmares, a sense of being lost in life, and increasing irritability.” Id. at 1019.

Almaghzar v. Gonzales, 457 F.3d 915 (9th Cir. 2006). Cited for the proposition that “U.S. courts and administrative bodies routinely use expert witness testimony on the psychological impact of torture in cases involving torture victims.” The court notes that the petitioner’s expert was allowed to testify at his immigration hearing that “post-traumatic stress disorder often impairs memory and the ability to concentrate, and that these symptoms explained the inconsistencies in Almaghzar’s prior testimony.” Id. at 919. The immigration judge disregarded the expert’s testimony, however, “concluding that Almaghzar’s fraud conviction for his role in a complex criminal enterprise in which he had sold methamphetamine for food stamps was inconsistent with Dr. Givi’s opinion that Almaghzar was incapable of complex, non-linear thinking.” The 9th Circuit held that this was was proper.

Hanaj v. Gonzales, 446 F.3d 694, 700 (7th Cir. 2006). Cited for the proposition that litigants typically argue over how much weight to give an expert’s testimony, not its admissibility. The court notes that an immigration judge allowed a psychiatrist to testify generally regarding PTSD at the petitioner’s immigration hearing. There is no discussion of admissibility of the expert’s testimony.

United States v. Yousef, 327 F.3d 56, 126 (2d Cir. 2003). Cited for the proposition that litigants typically argue over how much weight to give an expert’s testimony, not its admissibility. The court found that the district court did not abuse its discretion in finding that the expert “had been ‘bamboozled’ [by the alleged torture victim] and consequently discounting her testimony and conclusions.”

Zeru v. Gonzales, 503 F.3d 59, 72-73 (1st Cir. 2007). Cited for the proposition that litigants typically argue over how much weight to give an expert’s testimony, not its admissibility. The court noted “That the IJ considered Wattenberg’s testimony and reasonably discounted its evidentiary weight does not offend the Fifth Amendment.” And part of that testimony was that PTSD can cause memory loss.

Morgan v. Mukasey, 529 F.3d 1202, 1211 (9th Cir. 2008). Cited for the idea that “the Board of Immigration Appeals’ ‘brush-off’ of psychological reports finding that Petitioner suffered from torture related PTSD was an ‘error of law invalidating the decision of the BIA.’” This appears to be correct, but note that this is regarding an immigration hearing, where Daubert and the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure do not apply.

Next the amicus brief cites to a bunch of obviously non-binding international sources.

In sum, none of the authorities cited by the amici in any way suggest that Fabri’s testimony meets the requirements of Daubert in a district court setting. They cite no case remotely resembling the circumstances here.

Conclusion – Speculative, Non-Scientific, Non-Legal PTSD “Filtering” Testimony Not Admissible

The proposed expert testimony of “filtering” and reinterpreting a question despite remembering the traumatic event has no medical or legal foundation. It is wholly speculative, and appears to create a new theory for the purpose of the case. As such, under well-established, the testimony of Rasmea’s PTSD expert should not be admissible.

—————-

Case Resources re Expert Testimony:

Affidavit and Expert Report of Dr. Mary Fabri

Transcript of Testimony 10-2-2014

Transcript of Testimony 10-21-2014

Amicus Brief of Center for Constitutional Rights Supporting Fabri Testimony

Appeals Court Decision

Additional Affidavits of Smith and Jaransonin Support of Fabri Testimony

DONATE

DONATE

Donations tax deductible

to the full extent allowed by law.

Comments

This mass murderer is likely done. What’s especially fitting is that first hard time, then deportation back to the sandbox. Should give her lots to look forward to while she’s staring at the bars.

Welp, that about does it…

We don’t need to house and feed her. Just drop her off near the first Kurdish fighter’s camp.

Release her in Gaza. Hint she’s a mole

Don’t release her in Gaza if he is a mole. We don’t want to give Hamas any more assistance with their tunnelling.

It would be nice if PTSD made people forget.

How can she have been allowed to remain in USA after the 18 months knowing that she was imprisoned in Israel and for what reason? I don’t care what she thought the form meant, we know she was a terrorist… send her packing. now. why has it been 30 years?!?!!?

If her citizenship was not fraudulently obtained then she can’t ever be deported, no matter how good the reason. The only way to get rid of her is to find that she was never really a US citizen in the first place, because she knowingly lied on her application. Which she did.

Her crimes in Israel are not relevant here. The only matter before the courts is her fraud in obtaining first residence and then citizenship.

from article: “Rasmea was convicted of immigration fraud in federal court in Detroit in November 2014, sentenced to 18 months in prison and ordered deported after release from prison.”

Meaning, she wasn’t a citizen, and was ordered deported. we knew then about her past. she lied. even if she “thought” she wasn’t, we know her past.

Um, are you paying attention or are you asleep? That is the verdict that is under appeal. Meaning that whether she is a citizen is very much an open question. The state says she isn’t, she says she is. If she wins this hearing, and the subsequent retrial, then it will be established that she is a citizen and can’t be deported. If she loses this hearing, or she wins the hearing but loses the retrial, then she is not a citizen, serves 18 months, and is then deported.

PS: Either way, the reason she was imprisoned in Israel is completely irrelevant. It’s not even relevant whether she was guilty (which of course she was). The only relevant fact is that she was convicted and served time, and then lied about it when she applied first for US residence and later for citizenship.

What is admissible as evidence before a Court is whatever that Court deems admissible — until reversed by a higher Court.

I know it’s Halloween round about now, but Prof., the following does not sound so good:

” I’ve met the siblings of Edward and Leon and visited their graves, ”

Maybe it would have been better as, “I’ve visited the graves of Edward and Leon, and met their siblings”.

Yes, that is awkward. I’ll clarify.

Absolutely superb article.

Look forward to more like them.

So far this Judge has seemed very tied to the law, even under what I am sure was heavy pressure to exonerate this pot bellied savage. Here is hoping he is just as strict in his finding this time.

When did Ms. Odeh complete her visa application, in relation to her entry into the United States? I am relatively ignorant of immigration law, but I thought that visas were obtained prior to entry.

“Have you EVER been convicted/imprisoned?” could NOT have meant “in the United States” before she had entered the U.S.!

Let’s forget about the citizenship application for now. This person lied on her initial visa application, when the very same question could NOT have been referring to “in the United States.”

Lying on the visa application would not invalidate her citizenship.

Milhouse, the question asking “Have you EVER been convicted/imprisoned” was asked in the visa application BEFORE she had ever been in the US. It seems pretty clear that that question did not mean “Have you EVER in the US been convicted …?” She lied when she answered that

It seems to be a stretch to claim that the exactly same question had a different meaning on the naturalization application.

He whole defense is a stretch.

‘What are you talking about? Lying on a visa application makes you inadmissible. If you were inadmissible in the first place, you can not later go on and become a citizen.

Says who?

You seem to be saying that the fact you got to the US fraudulently somehow doesn’t mean your citizenship is invalidated.

No. If you committed fraud at any point in the process, you are not a citizen.

Says who? Obtaining a visa to enter the US is not part of the process of naturalization. Fraud in that process would not affect the naturalization’s validity, just as any other crime would not affect it. That’s why they ask these questions in the first place; they don’t expect truthful answers, they’re setting themselves up so they can retroactively invalidate it if it ever turns out that the applicant lied.

I find it amusing that a certain class of people think I hate Mexicans because I’m a Republican. It’s amusing because I’ve hung out with more Mexicans or Americans of Mexican heritage than they have.

To refer to but one example, I sharpened my Spanish at the San Diego Federal Building, as me and my comprades worked with each other to figure out what forms we needed to fill out. The “customer service” people were under instruction not to give us the least bit of information, and you couldn’t just tell from the title on the form what was what. It was all written in Washingtonian bureaucratese.

Bringing my Japanese wife into this country was an exercise in pain. And we’re supposedly allies. So I’m amazed you’re saying it’s going to be cool with the government if an immigrant lies on the visa application and later applies for citizenship. Because that’s not what the immigration lawyer who I eventually had to hire after I threw up my hands in frustration told me.

It doesnt’ matter what the US is “cool with”. The only thing that matters is whether the applicant ever became a US citizen, because once given that can never be revoked. Citizenship obtained by fraud is a nullity, legally it never happened, and thus she can be deported. If there was no fraud in that process then she’s a citizen and doesn’t need to care what the US wants.

How are we not in agreement here? Yes, citizenship obtained through fraud is a nullity. Yes, got it. But if part of the fraud involved lying on the visa application it is still a nullity.

When I spoke of the class of people who think I hate Mexicans, that was not directed at you, Milhouse. I was thinking of other people.