Exclusive Video Interview: Former VT Governor On His Challenge To Middlebury College’s De-Naming Iconic Mead Chapel

James Douglas: “They took the name off the building without even knowing for whom the building was named.”

Early one morning in September 2021, while most of Vermont’s Middlebury College campus was still asleep, workers arrived at the Mead Memorial Chapel. Tools in hand, they wrenched the rustic wooden sign bearing the Mead family name out of its niche above the entrance to the 105-year-old historic house of worship. It broke as it came out, exposing the bare brick wall behind it.

After the deed was done, the school pointed to Governor John Abner Mead’s “instigating role” in the Vermont eugenics movement as the reason for ripping his family’s name off the iconic chapel he endowed.

From now on, the school announced, it would be known as “Middlebury Chapel.” Or just, “the chapel.”

Mead’s descendants were outraged. Neither they nor the public had been notified in advance that the school’s most prominent and beautiful building would be severed from its donor’s family legacy.

The Mead family members, one of whom I spoke to and who wishes to remain anonymous, decided to sue the school.

To bring their lawsuit, they would first need to appoint a Vermont resident to serve as administrator of the estate, someone who was as upset as they were about the insult to their ancestor and his family’s name. They reached out to former Governor James Douglas.

Douglas stepped up: “Put me in, coach!”

The Rutland, Vermont probate court judge had never re-opened an estate this old, but he was prepared to do so in this case and appointed Douglas as the estate’s administrator.

As Governor of Vermont from 2003-2011, Douglas has a unique perspective: He is also an alumnus (’72) of Middlebury College and currently teaches there as Executive in Residence. And now, as administrator of the estate, he assumes the role of plaintiff in the lawsuit.

We talked about the estate’s litigation with the school, first reported on here, and about how Middlebury fits into the bigger campus cancel-culture picture. A longer clip with excerpts from our conversation is here.

Offer and Acceptance

In their complaint, Douglas and his lawyers say that Middlebury is in breach of contract for removing the Mead family name from the chapel.

And here, Douglas explains, is where Middlebury College becomes a very different story from other campus de-naming cases:

This is not, as the case in some other schools, [a situation] where they just wanted to honor some distinguished alumnus. [Mead] gave the chapel to the college, and he specified the name when he did so in 1914.

The Mead family descendants know this. One of them asked the school for documents related to John Abner Mead’s gift.

The school’s reply? Nothing to see here:

“Simply no evidence”?

That would be a compelling defense to the breach of contract claim—if it weren’t a complete fabrication.

The plaintiffs have the receipts, and they are all attached to the complaint. There is Mead’s offer letter marked up by hand to emphasize his intent that the chapel be named after his family and spelling out other conditions of his gift. And there are letters from the trustees gratefully accepting Mead’s proposal. If there were any question as to whether the college understood the conditions on which Mead made his offer, the handwritten resolutions of the Middlebury trustees not only accept the offer but incorporate verbatim Mead’s entire letter.

The estate has asked for a jury trial, says Douglas, because he believes “if a group of average Vermonters are presented with these facts they’ll understand and do what’s right and fair.”

The estate has also asked for monetary damages, including those arising out of Middlebury’s use of and benefit from the chapel. By removing the Mead name, they argue, the school has wrongfully benefited from his gift.

Mead Memorial Chapel has long been a draw to students and visitors. It figures so prominently in the school’s marketing materials that the public associates it with the school itself. You see it and you think: Middlebury College.

This is the college’s brand, Douglas says. … That’s why we argue unjust enrichment, because the college has had use of this wonderful structure for such a long time.

The school, meanwhile, has asked the court to dismiss the complaint.

“They took the name off the building without even knowing for whom the building was named.”

But what the school really wants to dismiss is the Mead family legacy.

Middlebury claims Mead’s name was placed on the chapel to honor himself and his wife. That is simply wrong, Douglas explains:

The Governor made it clear it was to honor his ancestors. So one question I often ask people at the college is – what do you have against James Mead or Peter Mead or Roswell Mead, his ancestors?

And “that is the sad irony”:

They talk about what a thoughtful and thorough process they had to make this decision. But they took the name off the building without even knowing for whom the building was named.

“Obviously, if they didn’t get the name right,” says Douglas, “it couldn’t have been a very thoughtful process.”

The college denies that Mead intended the chapel as a “forever” memorial to his forebears,” but Douglas disagrees:

The College would probably argue that nothing is forever. Well, I think that when you insist that a building be made of Vermont marble, it is forever. There are some marbles that are thousands of years old. So I think he had that intent.

Erasing the Past

It should go without saying that there wouldn’t even be a chapel if it weren’t for Mead’s offer to his alma mater in 1914 to build one “to be known as the ‘Mead Memorial Chapel,’” as a tribute to his forebears.

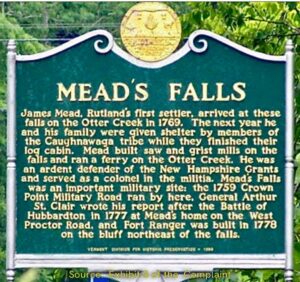

The Meads were old-stock pioneers, their lives devoted to community service from the time they settled in Vermont in the late 1700s. Their entire family history is set out in the complaint filed by the estate against the school. It records a series of “firsts,” including the arrival of Mead’s great-great grandfather, James Mead, the first settler in Rutland. He also served in the first state legislature and was later a colonel in the Revolutionary War.

In 1999, an historic marker was erected by the Vermont Division for Historic Preservation at Mead’s Falls to commemorate James Mead’s lifetime contributions.

But by 2021, historic markers such as these were not so much being put up as they were being pulled down. That was the year following the killing of George Floyd and the ensuing BLM riots, when major American cities descended into chaos. When protesters weren’t rioting or vandalizing and looting stores, they were toppling historic statues, many on college campuses, as we covered, for example, here and here. It wasn’t a time to honor history; it was a time to erase it.

And for politicians, it was a time to pander to voters by apologizing for the white men who authored that history.

That is what the Vermont Legislature did in the spring of 2021 when it formally apologized for past state-sanctioned eugenics policies, including legislation enacted in 1931 authorizing sterilization of at least 250 of its citizens.

The press ran with the politicians’ public show of unfelt sorrow and catch-phrased commitments to “doing the right thing” and “taking ownership” for the sins of other men who built the rich world we live in today and who are no longer around to defend themselves.

Show Me the Man and I’ll Show You the Crime

As if on cue, Middlebury College showed up with its man: Governor John Abner Mead. Mead was dead, white, and male. It was now just a matter of finding his crime.

That would take a “working group” to study Mead’s career and uncover his ties to the eugenics movement in Vermont—over the summer, when no one was around. Sure enough, they discovered evidence that had “fallen between the cracks.”

It all began with Mead’s Farewell Address, delivered in 1912, at the end of his term as governor.

In his speech, Mead suggested policies for the legislature to consider in the future, including certain restrictions on marriage licenses and a commission to study the use of a new operation called a vasectomy, which was a safer and more humane process of sterilization.

Those parting words, we’re to believe, were an urgent “call to action” resulting:

in a movement, legislation, public policy, and the founding of a Vermont state institution that sterilized people—based on their race, sex, ethnicity, economic status, and their perceived physical conditions and cognitive disabilities.

Douglas says “their implication of a racist motive is really offensive to the descendants and to me.” Mead interrupted his college studies “to join the Union Army, to fight slavery.” And, there’s no known evidence to support Middlebury’s suggestion that Mead’s motives were racist, says Douglas. He asked the school to show him the evidence, and “of course they haven’t,” he says.

Meanwhile, the legislation Mead recommended in 1912 was never enacted, because the next governor vetoed it. It was not until 1931—nearly twenty years after Mead’s address and ten years after his death— that “An Act for Human Betterment by Voluntary Sterilization” was passed into law.

They Never Have to Prove It

It’s hard to understand the “careful and deliberative process” that led the school to remove Mead’s family name from the chapel. How, exactly, did Mead’s recommendation lead “directly” to eugenics policies implemented 19 years later?

Douglas tried to find out. But when he asked to see the task force report, Middlebury’s lawyer told him it was confidential under the school’s records retention policy. And it would remain so for 75 years.

“So how about if you show me the minutes of the trustees’ meeting when they made this decision?” Douglas asked. “Oh, that’s confidential for 75 years, too.”

If the task force report and trustees’ minutes make such a clear case for defenestrating John Abner Mead, why not publish them?

Middlebury’s Free Speech Problem

Middlebury’s decision to erase the Mead legacy is part of a bigger struggle over freedom of expression on the Middlebury campus.

In 2017, the school made national news when students shouted down invited speaker and conservative author Charles Murray.

And in 2019, Polish conservative scholar Ryszard Legutko was cancelled at the last minute before he was to speak on campus. Douglas recalls the embarassing episode:

The guy came from Poland and a few hours before his speech the college pulled the plug on his presentation.

I had dinner with Professor Legutko after his ‘non-speech’ and he said in decades of speaking all across the world on campuses, this has never happened before.

…

It’s a Middlebury problem. We’ve had professors here threatened with discipline for controversial … remarks. Students come into me and say, “I can’t express my view in Professor So-and-So’s class.”

“It’s self-censorship, it’s academic freedom, it’s shutting down free speech,” says Douglas. The de-naming of Mead Memorial Chapel, “is just the latest episode” in the school’s ongoing history of suppressing speech.

Mead Was Mainstream in His Time and We Should Celebrate Him in Ours

Mead’s ideas about eugenics were mainstream in the early 1900s, Douglas explains. Vermont, like 28 other states during the progressive era, had a eugenics policy. Many celebrated individuals, including Helen Keller and W.E.B. DuBois, espoused eugenics. The United States Supreme Court, infamously upheld a state statute allowing sterilization of imbeciles. If Mead were judged in his time and place, he would be seen as progressive, and he was.

But more than that, the school has terribly mischaracterized Mead’s life and legacy:

Most people have a legacy that is mixed or not perfect. … You can find some blemish on any public official’s record. … As a retired professor here said, “I hope we are all not judged by our worst day.” Especially when it’s taken out of context by the passage of a century.

“We shouldn’t erase history,” says Douglas, “we should contextualize it.”

Here’s some context: If Mead were alive today, his 1914 bequest totaling over $75,000 would translate to over $2,000,000. Tearing his name off the building he donated because he once said something impolitic seems an odd way to express gratitude for a gift that has become an iconic symbol of Middlebury itself.

And that money didn’t just fall into his lap. When Mead, who was orphaned at birth, graduated from Middlebury College in 1864, he was nearly penniless.

John Abner Mead worked hard, fought in the Civil War, paid his way through medical school, saved his money, succeeded in business, built institutions, and actually “gave back” to his community—generously. His story of rising above his circumstances with diligence and industry is the classic American success story.

We should be celebrating it, Douglas says, not canceling it.

DONATE

DONATE

Donations tax deductible

to the full extent allowed by law.

Comments

May the Mead family name outlive Middlebury’s name.

My family arrived in Northern Vermont a few decades before Mead arrived in the south. After my ancestor’s marched south from the Upper Connecticut to the Battle of Bennington and later fought with Ethan I became so angry and disenchanted with what those Woke Crusaders from away brought to my Libertarian State that my wife and I left for points south after over 200yrs of history there. I hope everyone that destroyed the Republic of Vermont choke on it.

“The God’s of the Valleys are not the God’s of The Hills and you shall understand this.”

Ethan Allen to the King’s Governor of New York before taking up arms.

“They took the name off the building without even knowing for whom the building was named.”

Why the odd phrasing? Ah, a terminal preposition avoider.

If your readers are brought up short with that reaction, you’re no good at composition.

I blame Middlebury’s English department.

We should all, like, make an effort to, like, speak more neatly and stuff.

Like, do not aks who the bell tolls for, brah.

The phrasing is not odd; it’s poetic.

A BIG 10-4 on that, good buddy

It’s startling to see all these small colleges that I was considering attending turn up as woke idiocies. I went to Oberlin, which was good at the time, and just thought its subsequent turn for the worse was bad luck. It seems to be all over though.

Oberlin when I went was probably considered in the top 5 small liberal arts colleges in the US, along with Swarthmore. The latter has retained its standing. They all may now be woke, which IMO is the antithesis of classically “liberal”.

My alma mater has become a total disgrace; yet another example of academia’s slavish fealty to the vile Dumb-o-cats’ obnoxious Maoist thuggery, totalitarianism and intolerance.

I’m still majorly pissed about what happened a few years ago, when students tried to assault guest speaker Charles Murray, assaulted a woman professor who was escorting him, and — naturally — received no punishment for their outrageous and violent behavior. Every student involved in this assault should have been swiftly expelled.

It’s interesting how , over time, the language evolves

The article references the word “imbecile” as it was used a hundred years ago — that is, someone with an IQ roughly ~40-55.

Today, by contrast, an imbecile would be anybody who actually believes that attending Middlebury College would be a good way to spend the years between ~18 and ~23

I’m interested in the general counsel’s denial that any documents exist–how can she say that when they were attached to the complaint?