Controversial Cybersecurity Bill On Track to Pass Senate

on October 22, 2015

3 Comments

Today, a controversial cybersecurity bill aimed at making it easier for corporations to prevent hacking attacks advanced in the Senate with bipartisan support.

The Cybersecurity Information Sharing Act (CISA) in its current form would make it possible for corporations to share information about cyberattacks with each other---or the goverment---without having to worry about fielding privacy-based lawsuits.

The bill enjoys bipartisan support in the Senate---and has languished under bipartisan opposition, led by Kentucky Senator and Presidential hopeful Rand Paul.

From Reuters:

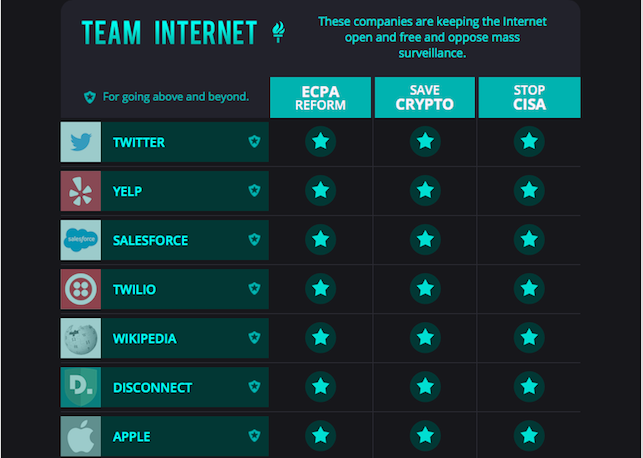

But many privacy activists and a few lawmakers, including Republican Senator Rand Paul and Democratic Senator Ron Wyden, vehemently oppose it. Several big tech companies also have come out against the measure, arguing that it fails to protect users' privacy and does too little to prevent cyber attacks.