Gibson’s Bakery v. Oberlin College – Trial Day 10 – It depends upon what the meaning of the word “support” is

Today was Day 10 of witness testimony in Gibson Bros. v. Oberlin College. The events giving rise to the lawsuit have been said to represent “the worst of identity politics.” You can read about some of the background on this case here.

As so often happens in courtroom trials, choice of words used by witnesses becomes an issue. This is, after all, the art of truth-seeking that trial lawyers love to hang their hats on, proving that what was said can be true evidence of what that person accused was thinking. And, of course, common defense is “I didn’t mean it that way.”

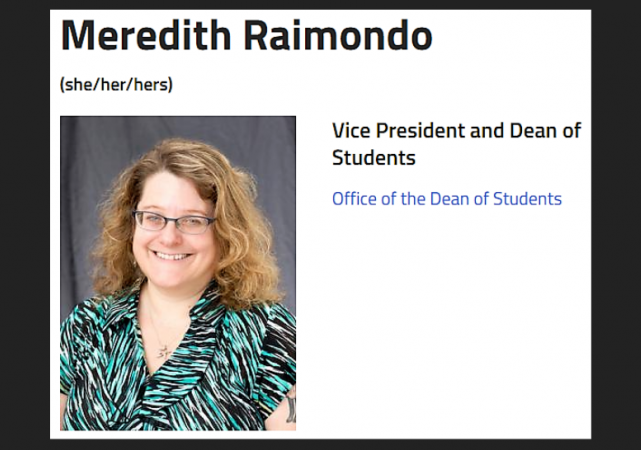

As Oberlin College began its defense that it didn’t libel or defame Gibson’s Bakery & Market, co-defendant Meredith Raimondo took the stand today. She is the current Dean of Students for the school, and was appointed on Nov. 1, 2016 – about one week before the shoplifting and subsequent protests occurred that started this legal imbroglio.

At issue verbally was her repetitive use of the word “support” for the student protesters. Her emails, texts, and previous testimony showed she liked to use the term “support” extensively. Many of the usages of that word were describing the school’s relationship with the protesters outside of Gibson’s on Nov. 10-11, 2016.

On Nov. 11, 2106, Raimondo and Oberlin College President Marvin Krislov sent a letter to the school community stating that “We want you to know that the administration, faculty, and staff are here to support you as we work through this moment together.” In an email sent out to senior administration officials on Nov. 23, Raimondo used the term “support” five different times in one paragraph according to evidence shown in court today.

One support reference had said that the Gibson’s food contract with the school would have resumed “had the Gibson’s been willing to support a resolution outside of the legal system.”

When defense attorney Richard Panza asked Raimondo to explain what “support” meant in her mind, she said, “What ‘support’ means in student affairs is to advise students and when appropriate to challenge them,” she said.

“Did you in any way “support” what the protesters were doing,” Panza asked.

“Our job was to focus on safety and lawful behavior,” she answered.

The goal of the defendants was to show her as a responsible college administration official, who acted as a link between the protesting students, the school and law enforcement. They tried to shoot down testimony that she was on a bullhorn for about a half-hour; she said it was about a minute at most a minute or so, instructing the students to not black sidewalks and to keep their distance from confrontations.

She also said she did not instruct students how to make copies of their flyers, and said she did instruct the protesting students to use a college building room nearby as a “quite space” area. “When people get emotional, giving them a place to calm down helps to keep fights and violence from occurring,” she told the jury

But Gibson’s attorney Lee Plakas was having none of these explanations of her role during his cross-examination.

“We see your use of the word support in many communications but you are saying the meaning of the word “support” by you is not in the common meaning we all think it is?” he asked. “As in, “support” meaning, ‘I’m in favor of what you are doing’ or ‘you’re right and I’m backing you.’ “

Raimondo responded quickly: “You can twist my words any way you want. No matter how you try to twist [them], it’s not what I meant.”

“I don’t take a side on the position being protested,” she continued. “I’m on the side of safety and lawful behavior. I support the students by what they need to do to keep the action safe and lawful.”

Raimondo said repeatedly under questioning by the college’s attorney that the school had nothing to do with production of the flyer and student senate resolution at issue in the case.

What the plaintiffs are trying to prove to the jury is that the school did not have to compose the flyer passed out at the protests, or write the resolution passed by the Oberlin College student senate. What they want to have the jury consider is that the college and Raimondo “supported” the students in what they did in the plain meaning of the term. So the perception of truthfulness is a key part of this civil case. Raimondo’s credibility is on trial in some respects.

The defense portrayed Raimondo as a highly-respected academic. She graduated as an undergrad from Brown University in 1991, majoring in American Civilization. According to her testimony today, after a brief turn as a teacher in the Los Angeles area after graduation, she then attended Emory University in Atlanta and received a master’s degree (her thesis was on inequality and social change in the U.S.) and a doctorate (thesis on the history of the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s).

Raimondo arrived at Oberlin College in 2003 and has been there in various capacities ever since.

Two incidents – one that was gone over today and another that will be subject of cross-examination tomorrow – will have a huge impact in this determination of truth.

Jason Hawk, editor for the Oberlin News Tribune, testified earlier in the trial that he had attended the Nov. 10 protest and that Meredith Raimondo gave him a flyer when he asked what the protest was about. Hawk said in testimony. “She argued we didn’t have the right to take photos of the protest,” He wrote in his initial story that the flyer that said “This is a RACIST establishment with a LONG ACCOUNT of RACIAL PROFILING and DISCRIMINATION” was “literature provided by the Oberlin College Dean of Students Meredith Raimondo, who stood with the crowd.”

The school didn’t like that description of the event in the local newspaper, and Oberlin College’s director of media relations, Scott Wargo, send Hawk and email to retract what they had written and replace it with “that literature was provided by the organizers and not Meredith Raimondo.”

Hawk insisted he was not wrong: “Sorry, Scott, but that’s simply not true. Meredith Raimondo handed me the literature.”

When emailed by Wargo what Hawk had said, Raimondo emailed back, “He is a liar.”

She had testified in court during her first time on the witness stand that she did hand Hawk one of the flyers, but claimed she did not know he was a media member at the time. She acknowledged again that did give Hawk a single flyer, even though she had said he was a liar for saying she did so.

The other item that might drop tomorrow is the schedule of subjects to be covered at a “Solidarity and Activist Lunch” at Oberlin College at an undetermined date. There were 20 students and eight deans listed as guests for the luncheon, and the plaintiffs got it in a discovery request from the defendants.

What is most interesting is that one of the subjects at this luncheon was “divestment of a relationship with the college and Gibson’s.” There is an Oberlin College print mark on the bottom, but Judge John R. Miraldi said he wanted to see proof of the tracking of the evidence from Oberlin College and the defense lawyers before questioning on the matter can continue. There is no date listed on it, but Meredith Raimondo’s title is listed as “Dean of Students.”

Meredith Raimondo’s testimony is expected to finish tomorrow morning, and former Oberlin College president Marvin Krislov, who was president at the time of the protests, is expected to testify after.

Daniel McGraw is a freelance writer and author in Lakewood, Ohio. Follow him on Twitter @danmcgraw1

————

WAJ NOTE: Our trial coverage is a project of the Legal Insurrection Foundation. Your support helps make this type of coverage possible.

CLICK HERE FOR FULL VERSION OF THIS STORY