How’s That Iran Nuclear Deal Working Out?

It’s working out quite well … for Iran

How’s the Iran nuclear deal working out?

I’m not asking the broader foreign policy question that Tom Nichols just addressed, but how is the nuclear aspect of the deal by itself working out?

According to Jonathan Broder of Newsweek, the deal is unraveling. And it is the fault of the United States.

Probably the biggest source of friction is a U.S. law that bars Iran from using the U.S. financial system and the American dollar, even indirectly. The law, enacted in 2012, was aimed at punishing Iran for a variety of alleged sins: the country’s ballistic missile program, human rights abuses and state-sponsored terrorism. Because these issues haven’t been resolved, there is virtually no chance Congress would repeal the law in the foreseeable future, experts say. As long as that statute remains in place, foreign banks holding Iran’s funds in dollars will be wary of doing business with the country.

The paragraph is more or less accurate in its description, but it has one big flaw. The term “alleged sins” is false. Instead of holding Iran responsible for its deplorable human rights record, its support of terror and its efforts at nuclear proliferation, Broder puts the blame on the United States for punishing Iran. If Broder’s correct then one way for Iran to get the sanctions to end is to stop engaging in the behavior that got them imposed in the first place. By calling Iran’s destabilizing behavior “alleged,” Broder lets them off the hook.

A few paragraphs down, though, Broder admits:

Experts say foreign banks are reluctant to engage with Iran for other reasons too. They cite Tehran’s outdated laws governing money laundering, as well as its lack of prohibitions against terrorist financing and corruption. “Because of a lack of transparency, it would be hard to have certainty that you’re not dealing with someone subject to sanctions or engaged in illicit activity,” says Katherine Bauer, a former Iran specialist at the Treasury Department.

Iran’s involvement in money laundering and terror support (no longer “alleged” it seems) were also factors in the 2012 Treasury designation. Again, here, the fault is Iran’s for its deceptive practices, lack of transparency, and corruption.

And of course, according to Broder, there’s also Donald Trump, and activist groups who opposed the deal and are warning businesses that if they deal with Iran they could find themselves on the wrong end of an American penalty. If these conditions persist, and Iran doesn’t get the money it deserves, Broder writes:

But on this issue, Iran gets a vote too. And if the promises of the accord remain unfulfilled, it’s not clear how long that country’s embattled moderates can keep the deal—and Obama’s legacy—alive.

Promises, to Broder, are the responsibility of the United States to fulfill according to Iran’s terms. To Broder, American Republicans are a bigger problem than Iranian “moderates.”

Suzanne Maloney, partially in response to Broder, wrote on Tuesday that the deal is in fact not unraveling.

By contrast, Iran’s dissatisfaction presents a serious diplomatic dilemma for Washington. But it should not be interpreted as evidence that the deal is “unraveling.” Rather, the chorus of complaints from Tehran demonstrates the accord signed in July 2015 is working exactly as it was intended—forestalling Iranian nuclear ambitions while amplifying the incentives for further reintegration into the global economy.

Maloney correctly ascribes most of Iran’s problems to its own misbehavior. So if everything is going as planned and it’s Iran, not the United States, that is responsible for the lack of a booming Iran economy, why is Iran complaining?

So if this was entirely predictable, why is Tehran crying foul now? Unlike in the United States—where the agreement’s shortcomings were oversold (if anything) rather than downplayed—in Iran there was a triumphalism with which the deal was sold domestically. This was mostly because of the peculiarities of Iran’s political system. To avoid the appearance of contravening the “red lines” articulated by Khamenei, the country’s ultimate authority, Iranian negotiators depicted the JCPOA as delivering wholesale sanctions relief. Rouhani described the outcome as a “legal, technical, and political victory” for the country, emphasizing that Tehran achieved “more than what was imagined.”

Iran’s politically motivated embellishments were exacerbated by the hype surrounding the deal, cultivated by entrepreneurs and aspiring middlemen who presented Iran in hyperbolic terms as “the best emerging market for years to come” and “one of the hottest opportunities of the decade.” But while it may offend the Iranian ego, the relative scale of the opportunity in Iran is more modest than other much-heralded economic openings, such as China. It is hardly inconceivable that many banks and other firms have simply chosen to sit this first round out.

I don’t buy this. To be sure, the Iranian regime is selling its achievement at home, but there’s a much different target for its complaints. That target is the Obama administration as Adam Kredo reported on Tuesday.

The Obama administration’s efforts to boost Iran’s economy and resurrect its financial sector are not required under the comprehensive nuclear agreement, yet the White House is undertaking this role to soothe relations with the Islamic Republic, nuclear experts told the Senate Banking Committee.

Iran continues to threaten to walk away from the nuclear deal unless the U.S. administration agrees to further concessions beyond the deal, sparking accusations that Iran is effectively “blackmailing” the White House, according to sources who spoke to the Washington Free Beacon.

Since the nuclear deal was implemented, “the Obama administration has missed the opportunity to push back against Iran’s legitimization campaign,” according to written testimony submitted to the Senate committee by Mark Dubowitz, executive director of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies. “Instead of insisting on an end to Iran’s continuing malign activities, the administration is now dangerously close to becoming Iran’s trade promotion and business development authority.”

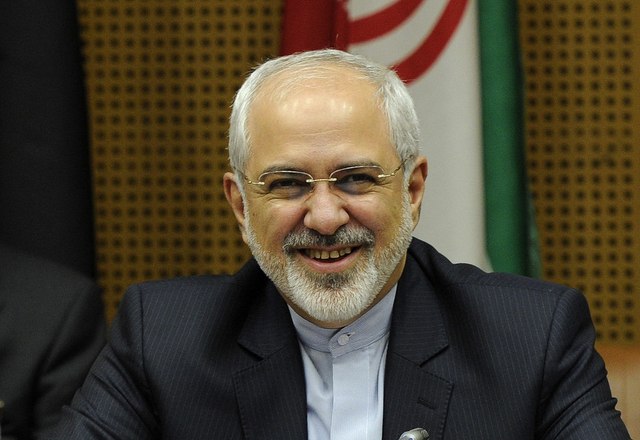

Since late last year, the administration has given in every time Iran threatened to scuttle the deal due to supposed American non-compliance. When the administration wanted to impose minimal sanctions on Iran for an October ballistic missile test, Iran threatened the United States, who then delayed the sanctions by several weeks. When Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif complained to Secretary of State John Kerry that the Visa Waiver Program didn’t include Iran and would thus have a negative effect on Iran’s ability to conduct international commerce, Kerry promised that the administration would issue visa waivers to Iranians or business people who had recently been in Iran. And most recently when Iran complained that it wasn’t receiving enough business due to American (non-nuclear) sanctions, Kerry traveled to Europe to urge European businesses to make deals with Iran and not fear penalties from the United States.

Maloney is correct that the administration should push back against the phony Iranian charges of non-compliance, but the administration keeps caving. She also quoted Zarif in a recent interview with The New Yorker saying “the United States needs to do way more,” with the added threat that “if one side does not comply with the agreement then the agreement will start to falter.”

DONATE

DONATE

Donations tax deductible

to the full extent allowed by law.

Comments

Let’s not use the word ‘blackmail’.

I prefer ‘extortion’. The hard ‘x’ makes it sound so much cooler.

Oy, what have you done to your borders? Much of your text is buried under all that gray stuff on the right.

I kept having to reload the page to get the text back in the readable space.

The middle east is headed for a limited nuclear exchange between Iran, Israel and Saudi Arabia. Five Years. Plan on it.

Start planning now how you will feed your family following the severe depression and hacking of the International banking system.

This is working out quite well not just for Iran, but for traitors Barack Obama and his commie-mommy, Valerie Jarrett.

Obama signed America’s death warrant knowingly by bowing to them without them having to demand it.