Public Health Officials Suggest Mystery Disease in Congo Could be Malaria

Interestingly, medical journals suggest there is a resurgence of malaria in the region….due to medical service disruption “exacerbated by COVID-19-related health service disruption.”

The latest death toll from the mysterious disease in the Democratic Republic of Congo is difficult to determine precisely due to varying reports. The last time I reported on the illness, which has hit children under 14 hard, it stood at 143.

Now that preliminary laboratory results are in, public health officials suggest that the disease in question may be malaria.

“Of the 12 samples taken, nine were positive for malaria but these samples were not of very good quality, so we are continuing to research to find out if this is an epidemic,” Dr. Jean-Jacques Muyembe, director-general of the National Institute for Biomedical Research in Kinshasa, told The Associated Press.

“But it is very likely that it is malaria because most of the victims are children,” he added.

On Tuesday, the head of the World Health Organization, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, also said most of the samples tested positive for malaria, but noted it is possible that more than one disease was involved. He said further samples will be collected and tested.

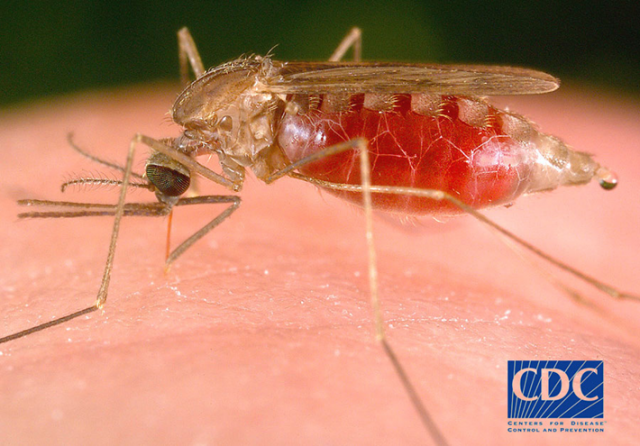

Malaria is one of the scourges of mankind, responsible for 4-5% of all human deaths throughout history (about 5 billion deaths in total). It id a parasitic disease caused by Plasmodium species that is usually transmitted through the bite of infected Anopheles mosquitoes. It remains a significant global health threat, with an estimated 247 million cases and 619,000 deaths reported in 84 endemic countries in 2021.

If it is malaria, it may turn out to be another disastrous unintended consequence of the “expert” pandemic response policies to COVID-19. Malaria is resurging in many African and South American countries as a result of health service disruptions attributed to the response to COVID-19.

From The Lancet, one of the oldest and most prestigious medical journals:

Malaria is resurging in many African and South American countries, exacerbated by COVID-19-related health service disruption. In 2021, there were an estimated 247 million malaria cases and 619 000 deaths in 84 endemic countries.

From the journal Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease.

..[T]he numbers of malaria cases and deaths showed increasing trends in 2020, and the most serious situation was observed in AFR. In particular, the West African countries had the highest malaria burden. Our analysis suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic has a negative impact on malaria control and prevention programs in various aspects .

These include reduced and delayed diagnostic and clinical visits, reduced access to healthcare services, medical resource shortages, disruption or delay of pillar control measures, and disruption to the availability of curative and preventive malaria commodities.

The symptoms of malaria usually appear 7-30 days after being bitten by an infected mosquito, but it can sometimes take up to a year to develop. Common symptoms include: Fever, chills, headache, muscle- and joint pain, nausea, and vomiting.

Those symptoms align with those reported with the mystery disease. Meanwhile, there are attempts by the media to tag this as “Disease X” (this is CNN).

Patients’ symptoms have included headache, cough, fever, breathing difficulties, body aches and anemia. Most of the cases and deaths are in children under the age of 14.

The unidentified illness, which some are calling “disease X,” has spread in the Panzi district of Kwango Province, an area that is remote and rural. There is limited health infrastructure or telecommunication, and travel is on dirt roads that have been flooded during the rainy season.

The area has high levels of malnutrition and low vaccination coverage, leaving children vulnerable to a range of diseases, including malaria, pneumonia and measles, Tedros added.

It should also be noted that the Kwango Province, where the outbreak is centered, recently experienced a severe food insecurity crisis:

In the western part of the country, including Kwango, inter-communal violence has been flaring, according to Amnesty International. And conflict in the country is exacerbating what the UN’s World Food Programme has deemed one of the worst hunger crises in the world. Millions have left their livelihoods as they have fled violence. Overall, some 25.6 million people are suffering from emergency levels of food insecurity, including nearly 4.5 million children who are critically malnourished.

Food insecurity in Kwango rose from acceptable to crisis levels between April and September, the WHO report said. Malnourished children are more likely to suffer severe consequences from measles and other diseases. The province also has low vaccination rates, leaving people in Kwango more susceptible to bad outcomes.

Malnutrition would significantly contribute to the loss of life among the young.

Of course, more evaluation is needed. But if this mystery disease does turn out to be malaria and is a consequence of pandemic health service disruptions, then the pile of pandemic policy failures is a truly ponderous one.

DONATE

DONATE

Donations tax deductible

to the full extent allowed by law.

Comments

“Disruption”? Do they mean the insane and false demonization of Hydroxychloroquine, which we were told was one of the most dangerous drugs on Earth (even though it is actually one of the safest drugs on Earth)?

People used to eat that stuff (and quinine) by the truckloads in Africa, all the time. Did that stop because of the political lying to support leftists’ COVID-19 policies?

Take some DDT and call me in the morning in 1960.

Malaria is a totally different world from most infections. It is a eukaryotic endoparasite that lay people often confuse with garden variety infections.

When dealing with a eukaryotic parasite, you have something that can adapt far better than any prokaryotic microbe. It’s still a relatively simple eukaryote, but it has a coordinated dispersal mechanisms to blast your bloodstream with toxic progeny all at once rather than randomly.

Anyhow, HCQ can fight it off slowly, but it takes time and a pretty healthy disposition to beat it. If you have liver disease, you can pretty much forget it.

Strangely, many researchers believe sickle cell anemia originated as a response to

.. Malaria. It seems to stop the parasite. But, of course, the impact on the anemia on the human body is excessive.

Yeah it did or at least all of the evidence points that way.

The mechanism is called stabilizing selection because having full blown sickle cell disease (double mutant) is too severe to be a fit phenotype and obviously susceptibility to malaria is bad in sub-Saharan Africa sans medicine. Therefore, the carrier (one mutant copy, one normal copy) who has only mild sickle cell symptoms is a rather fit phenotype in that environment because of the malaria resistance.

It’s time to reconsider the ban in DDT. Rachel Carson was simply wrong about the environmental effects of DDT.

That, or, DDT was Carson ‘s Corvair: an object used to sell books.

When I was a boy, the very first car I ever saw combust spontaneously (from the heat of its own engine, which ignited the upholstery in the rear seat) was a Corvair.

The Lancet engages in questionable political-ethical practices which serve to cloud its scientific analysis and conclusions.

A simple online search reveals ..

The Lancet Alters Editorial Practices After Surgisphere Scandal.

“The Lancet has announced changes to its editorial policies following the controversial publication and retraction earlier this year of a paper on COVID-19 patients treated with the antimalarial drug hydroxychloroquine.

The changes, described in an comment entitled “Learning from a retraction” last Thursday (September 17 2020), include alterations to peer review and other paper acceptance procedures, and have prompted mixed responses from the scientific and science publishing community.

“The proposed changes are a welcome addition, and I am glad to see Lancet implementing them,” Mario Malički, co–editor-in-chief of the journal Research Integrity and Peer Review, writes in an email to The Scientist. “However, they do not answer the questions at the core of the peer review process. How is it that the Lancet’s editorial team and reviewers (including a statistical reviewer) missed what the research community saw when the paper came out, [and] how….

Leave a Comment