Daunte Wright Shooting Trial Day 6: State’s Expert Say No Force Should Have Been Used

Defense scores points with police department use of force trainer, but prosecution’s hired expert claimed police should have just let Daunte Wright drive away his car and found him later.

Welcome to our coverage of the Kim Potter manslaughter trial over the April 11, 2021, shooting death of Duante Wright in a suburb of Minneapolis, when then-police officer Potter accidentally used her Glock 17 pistol in place of her intended Taser.

Strong defense cross of use-of-force Sgt. Peterson; weak defense cross of State expert Stoughton

Today was the sixth day of the trial proper and was most notable for a powerful cross-examination of use-of-force trainer Sergeant Mike Peterson by Attorney Paul Engh, and for the full testimony of the State’s use-of-force expert witness Prof. Seth Stoughton (who some of you will recall testified for these same prosecutors in the Derek Chauvin trial)—unfortunately, Attorney Earl Gray did a poorer than expected job of cross-examination of this State’s witness.

It also seems likely that the State will rest its case in chief tomorrow, and that the defense will begin to call their own witnesses and present their narrative to the jury for the first time in this trial.

Sergeant Mike Peterson, Use-of-Force Trainer: Cross-Examination

The cross-examination of Sergeant Mike Peterson, the Brooklyn Center Police Department’s use-of-force trainer, was conducted by Attorney Paul Engh. Peterson had provided his direct testimony in a lengthy—perhaps a couple of hours—questioning by ADA Matthew Frank yesterday afternoon. That direct questioning had been a bit like pulling teeth, with Frank asking explicitly leading question and Peterson largely limited to answering yes or no.

I expected the defense to do great work on their cross-examination of Peterson, who was clearly favorably disposed towards defendant Potter, and I was not mistaken in this expectation.

Engh had Peterson affirm that police officers have dangerous jobs, deal with dangerous and unpredictable people, and have to make life-and-death decisions in split seconds.

Officers have to respond to rapidly changing events and make decisions quickly, and they are provided with the discretion to do so.

Peterson affirmed that Potter was an attentive student, who attended all her training, and that as an FTO she had many more duties than would an officer just working alone.

The jury was reminded that Potter’s Taser 7 was new to her, received only a couple of weeks prior to her encounter with Wright, and differed in certain characteristics from her prior model Taser—most particularly in having far more black surfaces and fewer yellow surfaces than her prior Taser.

On a couple of occasions, Engh asked about Potter’s “gun” when he clearly actually meant “Taser,” quickly correcting himself, but the subtle “mistake” emphasized the mental possibility for confusing the two weapons.

Also emphasized was that even scenario-based training couldn’t really replicate an actual confrontation in the street, as you knew role players were not armed with real weapons and were not really trying to kill or maim you. Further, the scenario-based training around the period Potter had received her new Taser 7 had been substantially limited because of COVID constraints.

Engh also had Peterson agree that the “spark test” that Potter had conducted on six of her 10 duty shifts prior to her encounter with Wright were merely recommended to be done on an every-shift basis, and not required—nobody monitored if they were done, and no officer was reprimanded for failing to perform them on an every-shift basis.

Engh similarly made clear that pretty much all the other policies around Taser use were conditional on the totality of the circumstances, and were subject to officer discretion and competing interests. They were generally all of the “don’t do THIS … UNLESS you have a GOOD reason” guidelines.

It was also pointed out that Taser had everyone undergoing or providing training to sign releases that freed the company of liability for any accidental injuries that might occur—and that this was because accidents with Tasers can and do occur, despite best efforts to avoid them.

Peterson agreed that a suspect fleeing lawful arrest in a vehicle is a dangerous act, and puts the drive, the officer, and the public at risk of death or serious bodily injury.

Peterson also agreed that officers were trained to make decisions because failure to make a decision could also result in death or serious bodily injury—and that it was important to make a decision, even if that decision later turned out to be wrong.

Making a traffic stop is one of the most dangerous things an officer does, Peterson agreed, especially of someone with a warrant for a gun charge. Officers can’t simply let that person go.

Further, there’s a community interest in securing public safety by ensuring that unlicensed people aren’t driving, that uninsured people aren’t driving, that unregistered vehicles aren’t being driven around. Similarly for someone on whom there is an open arrest warrant for a gun charge being arrested, and for enforcing orders of protection.

Tasers were frequently used as tools for de-escalation, to convince suspects to comply with lawful orders, for the greater safety of everyone involved—and compliance was always what officers desired, rather than having to use escalating force.

You may recall that Judge Chu had early in the trial ordered that Graham factors not be explicitly referenced during the trial, but here Engh managed to sneak them into his questions in the context of asking about Minnesota’s statutes on use of force and use of deadly force.

Peterson agreed that police officers, no matter how well trained, were human beings, imperfect, and made mistakes.

Finally, Peterson agreed that Potter had a reputation for being both peaceful and law-abiding.

In total, cross-examination of Peterson took less than 40 minutes, in contrast with the prior day’s direct questioning of him, which took more than two full interminable hours.

Sergeant Mike Peterson, Use-of-Force Trainer: Re-Direct

ADA Matthew Frank followed cross with about 25 minutes of re-direct.

As so often has been the case with the State in general, and Frank in particular, re-direct came across as flailing and disjointed, and a rather emotive response to the damage inflicted on the State’s witness by defense cross-examination. Also, Frank improperly asked almost nothing but leading questions, apparently fearful of what open-ended responses would yield to the jury.

Frank mocked the notion that someone driving without a license or insurance was somehow inherently dangerous, but Peterson affirmed that in his experience people without a license and insurance also don’t tend to follow the rules of the road all that well generally. [fixed]

Frank tried to get Peterson to agree that it was inherently improper to Taser someone inside a vehicle, but Peterson corrected him to say this applied only in the context of a vehicle in motion, and that he himself had Tasered people inside a vehicle. Then Frank tied to suggest that someone who might shortly put a vehicle in motion was the same degree of risk as someone who already had a vehicle in motion, and Peterson responded that he supposed it depends on the nature of the force used.

Frank suggested that Potter, Luckey, and Frank Johnson didn’t actually have to arrest Wright, they could simply have let him go, that if a reasonable officer decides he can’t safely make an arrest he can use his discretion to not to so, and Peterson responded that was one of many factors for an arresting officer to consider.

These, and pretty much every other answer the State got out of Peterson on re-direct was of the “well, it depends” variety—and that’s not really all that helpful when the State ultimately has the burden of proving guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Indeed, “it depends” is pretty much a synonym for “reasonable doubt.”

Sergeant Mike Peterson, Use-of-Force Trainer: Re-Cross

Engh then got Peterson back on a brief, roughly 5-minute, re-cross examination.

Engh mentioned that Peterson had been asked by Frank if a good officer was expected to do a spark test each duty day, and Peterson had responded yes—but isn’t it also true that good officers also sometimes miss spark tests, and Peterson agreed that was also the case.

In evaluating whether someone is a good officer, Engh asked, you don’t merely look at their spark test record, you look at the entire body of their police career? Peterson again agreed.

Engh also had Peterson agree that the reason officers distinguish their use-of-force analysis between a car in motion and a car not in motion is that a car in motion is unambiguously so, but a car not in motion is much more subject to the officer’s discretion.

Sergeant Mike Peterson, Use-of-Force Trainer: Re-re-Direct

ADA Frank then came back for a brief, less than four-minute, re-re-direct of Peterson.

Aren’t officers trained that it’s dangerous for them to insert their bodies into a suspect’s car as Officer Johnson had, he asked, precisely because they could be dragged? Well, no, answered Peterson, we don’t train on that explicitly, it again “depends.”

Frank as apparently attempting to argue that somehow Johnson’s purportedly poor judgment in putting his body inside Wright’s vehicle somehow made Potter’s use of force unlawful, which is an interesting theory of the case.

Sergeant Mike Peterson, Use-of-Force Trainer: Re-re-Cross

Finally, Engh then got Peterson back on a 30-second re-re-cross examination.

During any traffic stop or other law enforcement incident, officers are trained and expected to assist and help each other.

Correct, answered Peterson.

And that was it for Sergeant Peterson.

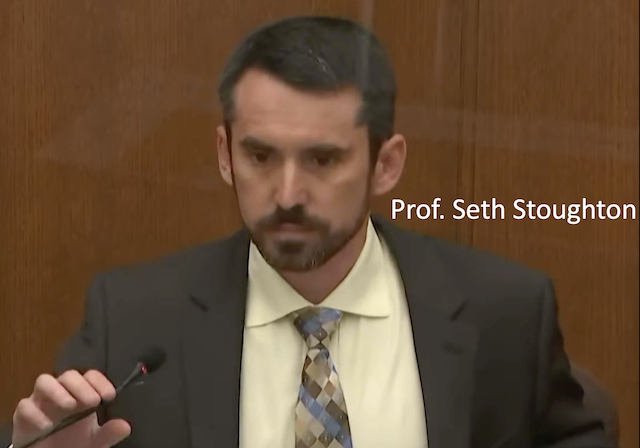

Professor Seth Stoughton, Use-of-Force Expert: Direct

The State’s next witness was Professor Seth Stoughton, a law professor who has become something of an anti-police use-of-force expert witness “gun for hire.” You may recall Prof. Stoughton from his retention as an expert witness by these same prosecutors in the Derek Chauvin trial. His direct questioning was conducted again by ADA Matthew Frank.

I won’t detail Stoughton’s more than two hours of direct testimony for the State, except to note that the State appears to have gotten what it paid for (about $10,000, in total)—in Stoughton’s expert opinion there was absolutely no manner of use of force, either deadly force or non-deadly force, that was or could have been lawfully or appropriately used upon Duante Wright by Kimberly Potter, regardless of whether her fellow officers were inside or outside of Wright’s vehicle when she fired her unintended gunshot, or whether Wright’s car was stopped in park or in motion at the time she fired.

I will note that there were several objections and at least one sidebar objecting to Stoughton attempting to definitively determine what Kim Potter’s subjective state of mind was during the encounter with Wright. This is impermissible as Stoughton can’t read Potter’s mind. It is permissible to note what facts a reasonable officer might consider in dealing with Wright, and point out the presence or absence of such facts, but that’s it.

To my eye and ear Stoughton once again came across as smarmy and fake but, of course, it’s unlikely the jurors have my prior experience with Stoughton in particular or gun-for-hire expert witnesses in general.

Stoughton did ultimately suggest that a reasonable officer in Potter’s position could have simply allowed Wright to flee the scene in his vehicle, along with his passenger—that would have been the conduct of a reasonable officer. After all, Wright could simply be picked up at a later date, given that the officers already knew his identity.

Stoughton Sidebar

This opinion would lead to a lengthy sidebar at the end of direct questioning, out of the hearing of the jury, in which the defense argued that it had opened the door to Wright’s many prior instances of fleeing from arrest and failing to appear at court dates—indeed, the warrant issued on the gun charge was a bench warrant for a failure to appear in court.

The defense now wanted to admit into evidence what they described as an inch-thick record of Wright previously fleeing arrest and failing to make court dates. Normally such would be excluded as character evidence. But the defense argued that the State’s expert had given the jury the false impression that it would be a small matter to simply let Wright flee and just arrest him later—when the actual facts were that Wright would simply flee every time officers sought to arrest him.

Indeed, Attorney Paul Engh promised to file a motion for a mistrial if Judge Chu refused to allow him to submit this record into evidence, pounding on the table as he did so.

Ultimately, the court decided this record of flight and failed appearances continued to be character evidence and declined the defense the ability to introduce it as evidence. We’ll have to see, I suppose, if Engh follows through with his motion for mistrial—a mistrial that would obviously be denied by the judge who had just declined to admit the evidence in question.

Professor Stoughton, Use-of-Force Expert: Cross-Examination

The roughly one-hour cross-examination of Prof. Stoughton by Attorney Earl Gray was substantially weaker and more meandering than I had expected it would be—Gray has consistently delivered a very strong performance on cross-examination for the defense.

Gray started off by asking Stoughton to confirm that he’d suggested that what a reasonable officer should have done was simply allow Wright to flee—and Stoughton flatly denied having said anything of the sort.

Frankly, Gray dropped the ball here. Stoughton is the kind of expert witness who, if you paraphrase his statement with one single word differing from the actual statement, will flatly deny having made the statement—meaning, the paraphrased statement, even if it is substantively identical to the actual statement. Gray’s paraphrase was not a precise quote, so Stoughton denied the statement. For some reason, Gray seemed unable to trap him in this slippery conduct.

That said, certainly the jury heard Stoughton’s original statement that allowing Wright to simply flee would have been the decision of a reasonable officer, while no amount of force by Potter under any of the disputed circumstances here could be lawful or appropriate, and hopefully, they took note of Stoughton’s less than honest denial.

Gray also reasonably mocked Stoughton’s claim to being a former law enforcement officer. While technically true, it appears that Stoughton’s less-than five-year career was mostly spent as either a trainee or doing paperwork, without serious street time or experiences. Even that minimal experience was 15 years in the past. Gray also exposed that even during his brief police career Stoughton had failed to attend assigned use-of-force training, and had never himself been a use-of-force trainer.

Throughout all of this Stoughton again came across to my eyes and ears as less than honest, refusing to answer direct questions with a simple yes or no answer—as should be done on cross-examination—and instead providing lengthy replies that appeared intended to deceive and mislead rather than inform.

For example, when Gray asked if Stoughton had ever been a use-of-force trainer, Stoughton did not honestly answer that he had not—he answered, instead, that he had use-of-force certifications. All this meant is that he’d been as a student in some classes. When Gray asked again, Stoughton now replied that he’d once written some use-of-force policies. When Gray asked a third time, Stoughton replied that he’d written some reports on use-of-force events.

This kind of shady evasiveness was constant throughout Stoughton’s testimony. How much of it the jury recognized is unknown to me.

Cleverly, Gray asked Stoughton about his retainer contract on this case and asked if it was correct that Stoughton stood to make up to a maximum of $50,000 on this case. Stoughton once again answered evasively—so Gray whipped out the contract, and had Stoughton read that portion aloud. In fact, Stoughton stood to make up to a maximum of $95,000 consulting on this case.

Now, in fact, Stoughton will probably make about $10,000 on this case, but that extravagant $95,000 figure is sure to stick in the juries heard.

There was, however, a lot of value that I felt Gray left on the table during this cross-examination. For example, Stoughton had spent about 30 hours arriving at conclusions on a use-of-force event in which Kim Potter had mere seconds to make a life-or-death decision. Also, Stoughton was not fighting a violently resisting suspect while doing his analysis.

Further, Stoughton had the benefit of multiple synchronized videos, and some kind of laser-mediate model of the events and, obviously, Potter had none of that on the scene.

Further, what Potter’s body camera would show under these circumstances was substantially different than what Potter’s eyes, with their wider field of view and ability to rapidly scan around, were likely to have seen.

Further, the screen captures used by Stoughton in his direct testimony at precise time points did not accurately represent the rapidly evolving, dynamic, violent, and dangerous environment in which Potter was making her human decisions.

Some were just half-missed opportunities—for example, Gray pointed out that the new Taser model Potter had received just a few days before her encounter with Wright had far more black and far less yellow than had her previous model of Taser. And that’s true—but Gray failed to use the actual models of Taser as demonstrative exhibits to show convincingly how much this was the case.

Around the end of cross-examination, Gray did compel Stoughton to concede that of the roughly 30 use-of-force cases on which he had consulted, more than 25 of them were cases in which he’d served a plaintiff suing a police officer in state or Federal court—the clear implication being that Stoughton is an anti-police expert witness gun-for-hire, rather than a genuinely impartial expert.

Professor Stoughton: Re-direct, Re-cross

There was also a brief re-direct by ADA Frank and a re-cross by Gray, but neither really amounted to much:

Arbery Wright, Father of Duante Wright: Direct

The final witness of the day was Arbery Wright, father of Duante Wright. He essentially testified that his son was a good boy. The defense did not object during this direct testimony, but only because they had a standing objection before the court at the start. There was no cross-examination of this witness.

End-of-Day Motions

As court wrapped up for the day it became clear that the State would be resting its case in chief tomorrow, either immediately upon court coming into session in the morning or perhaps after one or two more brief witnesses.

In preparing to hand the proceedings over to the defense, however, the State had several motions and matters they wanted the court to resolve, two of which are particularly notable.

First, they noted that the defense witness list had perhaps as many as a dozen character witnesses for Kim Potter, and they objected to that number as unnecessarily cumulative—which is quite a laugh considering how much cumulative evidence the State itself had presented in its case in chief. Nevertheless, the defense agreed to call no more than three character witnesses.

Second, the State noted that it appeared that the defense was planning to have its own use-of-force expert speak to matters of deadly force, which the State found objectionable because there was nothing about deadly force in that expert’s report shared with the State. The State thus claimed inadequate notice and wanted the defense use-of-force expert prohibited from discussing matters of deadly force entirely.

The defense response was that their expert was privileged to respond to the testimony of the State’s own experts and other witnesses made during the course of the trial, of which the defense could not be fully aware until that testimony was heard. Given that this testimony had covered deadly force matters, the defense expert was therefore privileged to respond to that testimony on deadly force matters.

Judge Chu was in the moment undecided on the issue and took it under advisement.

Frankly, if it’s true that the defense expert had failed to address deadly force in his own earlier analysis, that seems a rather grave shortcoming that should not have been permitted by the defense—a serious own-goal by the defense team.

THURSDAY: DAUNTE WRIGHT SHOOTING TRIAL DAY 7 LIVE

Be sure to join us at Legal Insurrection tomorrow morning for our ongoing LIVE coverage—including real-time commenting and streaming of the trial proceedings, starting at 9 am CT, and then again at day’s end for our analysis of the day’s events.

Until then:

REMEMBER

You carry a gun so you’re hard to kill.

Know the law so you’re hard to convict.

Stay safe!

–Andrew

Attorney Andrew F. Branca

Law of Self Defense LLC

Nothing in this content constitutes legal advice. Nothing in this content establishes an attorney-client relationship, nor confidentiality. If you are in immediate need of legal advice, retain a licensed, competent attorney in the relevant jurisdiction.

DONATE

DONATE

Donations tax deductible

to the full extent allowed by law.

Comments

“…but Peterson affirmed that in his experience people without a license and insurance also tended to follow the rules of the road all that well generally.”

I think NOT

Quite right, my error, fixed.

Unbelievable.

Earl Gray should’ve at least challenged the expert on his conclusion that the use of a taser would’ve been unjustified based on the vehicle crash risk. Even if Wright were able to get the car in gear and hit the gas while being tased, either the prongs would’ve flown out or the taser would’ve been pulled from Potter’s hand. In order for electricity to flow, the prongs mist be in AND the trigger mist be depressed. So once he drove off, no more electricity.

He also should’ve played the dash cam video that shows Sgt. Johnson still in the passenger side when the shots are fired. He only came partially out of the vehicle when she yelled TASER.

The X7 model is automatically going to give a 5 second discharge regardless of if the trigger is depressed or released. The only way to cut it short is to move the switch back to the off position. This was changed from the older models to prevent people from shocking for too long or not long enough.

I’m torn here. Yes, the defense team could have done a better job crossing the state’s hired gun. But the alternative would be to elicit relevant testimony from their OWN use of force expert and go about their business as if the state’s expert is a ranting homeless person who hasn’t showered since Lost was airing original episodes.

Arguing with an idiot has two possible outcomes. You might convince the jury that he’s an idiot, but you also run the risk of convincing the jury that you consider it essential to refute his testimony. Might be good strategy to get your man on deck and ready to step up to the plate as soon as the prosecution rests.

I agree, they did enough to show that the “expert” wasn’t very knowledgeable, professional, or reasonable. Now they can go through and have their own use of force expert give a hopefully rational opinion that agrees with the facts and evidence already given. Plus, there’s a remote risk he would actually give a response that was damaging to the defense or redeem himself – why risk it when it isn’t needed any more.

The real issue is this hack of a judge is unwilling to demand the witness answer the question as asked and is unlikely to properly restrict the prosecution to a legal avenue of questioning. She’s happy to oblige the prosecution when it comes to cumulative evidence, opening the door, and everything else but not apply the same standard to the defense. I’m not sure if she is just completely incompetent or if she is actively corrupt, but she should clearly be in the defense chair, not the judge’s seat.

Maybe Earl raised to the bar for himself too high. Being able to quarterback from the couch makes it much easier but we don’t know what Earl’s team has for a planned during his defense.

Earl also appeared to be ill, especially the day before and we don’t know if that effected him as well. The so called expert contradicted himself and the actual officers in the field every day. Hopefully Earl has saved some arrows especially if we ever get to a closing.

“… He essentially testified that his son was a good boy. …”

Why doesn’t this open the door for testimony that his son was not a good boy?

I agree, but it’s the same issue as going after the mother. Regardless of the kind of person Daunte Wright was, you expect a parent to say that he was a good boy who never did nothing wrong. Going too hard on a grieving parent is likely to turn the jury against you. It definitely doesn’t make it right though.

It’s not a matter of going after the parents, it’s that this should have opened the door to presenting Wright’s whole criminal record to the jury. And that would convince most of the jury that the cop’s worst mistake was in going for her taser instead of her gun to begin with.

I agree completely.

Once the testimony from the father came in, the “victim’s” character traits have been placed in issue before the jury.

It was not necessary to cross examine the father on these matters, which would risk alienating the jury.

Rather, the most effective way to proceed would be to not cross examine any family members, and then bring in a parade of character witnesses to attest to the “victim’s” propensities for violence and anti social behavior.

I would question how the paid whore qualifies as expert under the daubert standard ( or the mn state equivalent)

I don’t see anything in his history the indicate that he is actually an expert. – anti police activist doesn’t meet the test

If I were on the jury, the prosecution’s assertion that the police should have let an unlicensed and uninsured driver, with an outstanding warrant, resist arrest and drive away would be the last straw. They are either lying or complete fools. There is now reasonable doubt (at least) about everything presented by the prosecution, and so I’ve already arrived at not guilty.

The words “professor” and “expert” should never be paired in the same sentence. Academia spawns radical progressives who should never be in a courtroom testifying with their bias.

Look up the word “Cheesedick” in the dictionary. Professor Stoughton’s picture is found next to it. This guy wouldn’t know a real cop if one hopped up and bit him on the ass.