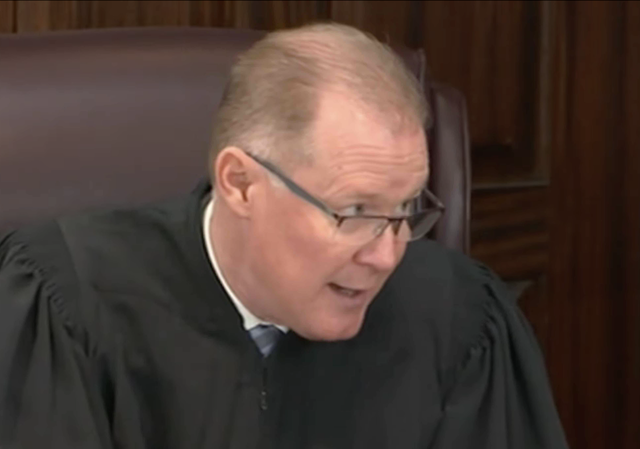

Arbery Case Trial: Judge Walmsley Drops the Ball On Ambiguous Citizen’s Arrest Law

Apparently the jury is to figure out how to apply a citizen’s arrest law that befuddles the lawyers and judge.

Today the jury heard the last of argument and received their jury instructions in the Arbery case trial, in which defendants Greg McMichael, Travis McMichael, and Roddy Bryan are each facing a count of malice murder, four counts of felony murder, and then the four predicate felony counts (two for aggravated assault and two for false imprisonment).

In the interests of keeping our coverage somewhat orderly, I’m going to address each of the day’s major events—the closing rebuttal of ADA Linda Dunikoski and the reading of the instructions to the jury by Judge Timothy Walmsley—separately. I covered the Dunikoski rebuttal in my previous piece of content, so here I’ll cover Judge Walmsley’s instruction of the jury.

Well, more accurately, I’ll cover the small portion of that instruction that’s the part that really matters here—the instruction on citizen’s arrest, §17-4-60. Grounds for arrest. And that instruction was an exercise in patent professional failure of duty on the part of Judge Walmsley.

This entire case essentially hinges on the question of the underlying citizen’s arrests. If the effort to make a citizen’s arrest of Ahmaud Arbery was lawful, then everything that follows was likely also lawful.

Conversely, if the effort to make a citizen’s arrest of Arbery was unlawful, then everything that follow was also likely unlawful.

And both sides fully understand this. In particular, ADA Linda Dunikoski is fully aware that if she loses the jury on the question of citizen’s arrest, she loses the trial entirely.

Naturally, then it’s in her interest to have the citizen’s arrest statute interpreted as narrowly as possible—and there’s definitely room for interpretation in this statute that was first made law back around the Civil War, and makes use of legal terms of art that likely don’t mean today what they might have meant back in the day.

Certainly, nobody drafting a citizen’s arrest statute today would construct it as this one is constructed.

The amount of ambiguity in the statute is really remarkable if only because of the statute’s brevity—it is only two sentences long. Those two sentences are:

A private person may arrest an offender if the offense is committed in his presence or within his immediate knowledge. If the offense is a felony and the offender is escaping or attempting to escape, a private person may arrest him upon reasonable and probable grounds of suspicion.

My own reading of that statute, applying normal rules of statutory construction, is that the two sentences present two different scenarios for a citizen’s arrest. The second sentence refers explicitly to a felony scenario and sets out certain requirements for that scenario that differ from the requirements set out in the first sentence. My reading is that the first sentence is therefore contemplating the alternative criminal scenario, the non-felony, the misdemeanor.

So, if the citizen’s arrest is being made for a serious felony, like murder, the person making the arrest is required to have reasonable and probable grounds of suspicion, which Judge Walmsley is interpreting as probable cause. Fair enough.

If the citizen’s arrest is being made merely for a misdemeanor, however, then probable cause is not enough. After all, an arrest is a real burden on a person’s personal liberty, and ought not be done lightly

Before we’ll allow a citizen’s arrest for a relatively minor crime, then—imagine shoplifting, for example—we’ll require more than just probable cause, we’ll require that the offense was committed in the presence of the person making the arrest, or that they have immediate knowledge of the offense (perhaps observed from a distance, for example).

So, my reading of this citizen’s arrest statute is that the first sentence refers to arrests premised on a misdemeanor offense, and the second sentence refers to arrests premised on a felony offense.

ADA Dunikoski urges a different reading of this statute. She argues that the first sentence is supposed to apply to all citizen’s arrests, whether for misdemeanor or felony offenses, such that any citizen’s arrest requires that the offense be committed in the presence of or with the immediate knowledge of the person making the arrest. The second sentence then adds additional conditions—the probable cause requirement—that must be met in the case of felony arrests.

This construction makes no sense to me, if only from a public policy perspective. Why? Because it makes it easier to make a citizen’s arrest, to constrain a person’s liberty if they’ve merely committed a misdemeanor like shoplifting than if they’ve committed a heinous felony like murder. That doesn’t make sense to me.

In addition, if we’re supposed to read in the “presence/immediate knowledge” into the second sentence, then the “probable cause” language in the second sentence serves no purpose.

If the offense occurred in your presence or with your immediate knowledge you have a degree of certainty that’s vastly greater than mere probable cause—you know for certain that the offense happened. Probable cause is merely a probability that it happened. That’s less than certainty.

It’s like saying that before you can make any arrest you have to be 100% certain of the offense, but before you can make a felony arrest you also have to be 51% certain. That makes no sense.

So, as you might expect, I favor my reading of the Georgia citizen’s arrest statute over the reading that ADA Dunikoski urges.

In any case, however, at the end of the day, the question of how this law is to be applied in this criminal trial is not up to me, and it’s not up to ADA Dunikoski

And most definitely of all, it’s absolutely not up to the jury, whose job is to be the finder of fact, to work through any ambiguity of evidence—not to work through the ambiguity of law.

The person in charge of the law in a trial is the judge—in this case, Judge Timothy Walmsley. It is his duty to decide how the law is to be applied to the facts as the jury determines those facts to be proven or not proven.

And this Judge Walmsley abjectly failed to do. And in a trial with three defendants looking at life in prison, that’s a contemptible professional failure.

Remember—the key issue is whether the two sentences in the citizen’s arrest statute are intended to be melded together so that both apply to all arrests, or whether the conditions of the first sentence refer to misdemeanor arrests and the conditions of the second sentence refer to felony arrests.

That’s the fundamental issue that Judge Walmsley needed to resolve.

And he did not.

Here’s the video and a transcript of the relevant portion of his instruction to the jury on citizen’s arrest, with the critical paragraph italicized:

The private person may arrest an offender if the offense is committed in his presence or within his immediate knowledge. If the offense is a felony, and the offender is escaping or attempting to escape, a private person may arrest him upon reasonable and probable grounds of suspicion.

At no point does the Judge tell the jury whether they are to treat the two statutory sentences as both applying in all arrests, or whether the separate felony conditions are to be independently applied in the case of an arrest predicated on a felony offense.

So with all the legal experts in that courtroom—three attorneys for the State, and apparently 6 attorneys for the defense, plus Judge Walmsley—we are going to leave the fate of these three defendants to however the jury decides to interpret an ambiguous statute that appears to befuddle even the experts.

It’s ridiculous.

It was the duty of Judge Walmsley to decisively construct a non-ambiguous jury instruction from this ambiguous statute. Sure, maybe a later appellate court would decide he’d done it wrong, and reverse him—but at least he’d have done it, which is his duty.

I would also note, that had Judge Walmsley done his duty and resolved the ambiguity of this statute, there’s only one possible legally-sound outcome—that the two sentences not be conflated, but rather be treated separately.

Why is that? Because under the legal doctrine of lenity, when a criminal statute is ambiguous, that ambiguity is always to be resolved in the favor of the defendant, never in the favor of the State. It is the government that drafted that statute and passed it into law, not the defendant. If they left in ambiguity, that’s on the government, not the defendant.

In short, Judge Walmsley dropping the ball on this all-important citizen’s arrest jury instruction simply makes this entire trial little better than a train wreck, and any guilty verdict this jury delivers is inevitably tainted by the failure to provide the jury with clear and unambiguous instructions on the key legal issue in the case, the issue that determines guilt or acquittal for these three men on charges that would put them in prison for the rest of their lives.

It’s contemptible.

Sigh.

In any case, here’s the entirety of the instruction of the jury by Judge Walmsley—other than the bungled citizen’s arrest jury instruction, everything else was boringly common:

OK, folks, that’s all I have for you on this topic.

Until next time:

Remember

You carry a gun so you’re hard to kill.

Know the law so you’re hard to convict.

Stay safe!

–Andrew

Attorney Andrew F. Branca

Law of Self Defense LLC

Nothing in this content constitutes legal advice. Nothing in this content establishes an attorney-client relationship, nor confidentiality. If you are in immediate need of legal advice, retain a licensed, competent attorney in the relevant jurisdiction.

DONATE

DONATE

Donations tax deductible

to the full extent allowed by law.

Comments

A black robe doesn’t automatically make you intelligent or honest. We’ve seen evil corrupt democrat black-robed hacks in action.

Now we’re watching intellectual mediocrity in action.

“A black robe doesn’t automatically make you intelligent or honest.”

Q: What do you call a lawyer with an IQ of less than 75?

A: Your Honor.

I think the defendants lose on both points. They didn’t have immediate knowledge that Arbery committed a crime, and the crime (sorry, I don’t know if trespassing on a construction site was formally stipulated) was a misdemeanor anyway. But sadly, this is what you get in Medieval Dixie–the KKK playbook, “Codified Vigilantism”, Chapter 2: Citizen’s Arrest. Geez, the last time I ever heard of this crap being invoked was when Gomer Pyle went nuts and did it–to like everybody–on an old Andy Griffith rerun.

Ah, yes, the typical liberal painting Southerners as shoeless hicks.

So, before going any further would you like to make any more egregious insults about people whom you don’t know and who have nothing to do with this article or case?

Because its seems like you were mainly intending to parade your progressive bigotry, rather than contribute anything adult.

But do go ahead; no surer way to see what kind of human you are than to let you talk.

Consider this alternate explanation for the statute language: First part says if you saw them do it you may arrest them no matter what the crime was. Second part says if it was a felony and they are trying to flee you only need probable cause to arrest them.

In my interpretation the construction is based on level of certainty not on level of crime.

If you did not see them do it and it was only a misdemeanor it does not matter if they try to escape you cannot arrest them.

Finally, if you did not see it, it was a felony but they are not running away you can’t arrest them either.

I don’t think these men were lawful in their attempts to arrest this man since they had no first hand knowledge and it was not a felony.

“It’s ridiculous”

snip

“It’s contemptible.”

Sums it up nicely.

Thanks Mr. Branca.

beware of anyone with the weird combover

see Schumer, Biden

Sorry but that’s not a comb-over.

Which way do you think he should comb it? Or, what is weird about it? Or, what, he should shave his head?!!

APPEAL

This is ripe for appeal if there is a conviction. But I think jury will be hung. There is too much emotion and irrelevant facts thrown against a wall for jurors to make a simple decision.

Is it ripe for appeal? Does the judge failing to give clear guidance constitute grounds for appeal? It is a scenario I have not heard before.

Instructing the jury incorrectly on the applicable law would certainly be reversible error on appeal. But that will be cold comfort for the defendants if they end up being convicted because the judge muddled the law for the jury. The defendants will still end up in prison for however many months, or years, it takes for the appeal to be decided.

The Judge’s lack of action to make a ruling on this point is another failure of our ‘elite’. This is admittedly a high profile case, tinged with racial issues legit or not, with the potential to spiral into nationwide rioting. His failure to make a decision on the law and punt this job to the jury demonstrates either abject cowardice or gross incompetence IMO.

Georgia is one of the states that has jury nullification built into their constitution.

Art I Section I Paragraph XI:

Right to trial by jury; number of jurors; selection and compensation of jurors. (a) The right to trial by jury shall remain inviolate, except that the court shall render judgment without the verdict of a jury in all civil cases where no issuable defense is filed and where a jury is not demanded in writing by either party. In criminal cases, the defendant shall have a public and speedy trial by an impartial jury; and the jury shall be the judges of the law and the facts.

Then he should have put that explicitly in his instruction, and also informed the jury of the Rule of Lenity. He should have said, “The first question that you will have to answer, before you consider anything else, is what does the citizen’s arrest law mean; there are two possible interpretations: [description of both] and it is up to you to decide which is correct. If you can’t make up your minds, then you must accept the defendants’ proposed interpretation”.

Yeah, that’s not going to happen. The Georgia Supreme Court ruled that judges do not have to instruct jurors in their right of nullification. I had jury duty three times when I lived in Georgia and we were always told we had to follow the Judge’s instructions. I knew better but never sat on a jury trial where I thought it was applicable.

That’s fine. In that case he should instruct them what the law is. You can have it either way, but you can’t have it both ways. You can’t say he’s leaving it to them because the constitution says he should, but he’s not going to instruct them that he’s doing so.

I mentioned elsewhere that this instruction was mandatory in Maryland, but only there. As you point out, there are other states (such as Pennsylvania) where the constitutional provision is crystal clear, and yet the “courtroom professionals” uniformly fail to instruct the jury of this right. Thanks for letting me know about Georgia.

Judge Walmsley:: “I love my comfortable position and the high social status of being a judge. Therefore I will completely avoid doing the hard, unpopular part of my job to avoid any threat to what I have.”

…where the person is trying to escape…

Or the felony where the person is not trying to escape.

A good point. A question for Mr Branca then, what is the objection to the following construction?

A citizen’s arrest is permitted for any crime committed within someone’s presence or immediate knowledge. If these conditions are not met, they must have probable cause to believe the person is attempting to escape after committing a felony.

This seems to be a reasonable construction that is equivalent to saying you can arrest for any event on 100% certainty (you saw it), but if you didn’t you need both probable cause (51%) and the criminal must be escaping the scene of a felony. It’s not the crime that is treated differently, but the knowledge of the arresting citizen about the crime in question.

From what I have read about last week’s charging conference arguments, this is pretty much what the judge decided on over the objections of the defense. The critical issue for the defense here is reading the statute to require the flight and the felony to be contemporaneous. I think the defense has a reasonable argument that the McMichaels had probable cause to believe Aubrey had stolen property from the site at some point, but the argument that they had probable cause that day is much weaker. Given this reading, I think the judge’s instruction’s were quite clear. They were in effect – the defendants had no immediate knowledge of a crime, so they have no authority under the first sentence to arrest. For the second to apply, the jury must believe a reasonable and prudent person would find probable cause that Aubrey was escaping just after committing burglary,

That is exactly my interpretation of the wording. Probable cause is less exacting a standard than “you saw it happen” – which is appropriate if a felony (not a misdemeanor) and he is escaping, if not arrested. It is especially in the public interest that felons not escape.

But the crime they were attempting to arrest him for was not stealing, which they did not have probable cause to believe he’d just done, but burglary, which they did.

Burglary : entry into a building illegally with intent to commit a crime, especially theft.

Theft : the action or crime of stealing.

Reading the two statutory provisions together, as one must, I hold that the first sentence authorizes a person to make an arrest for any offense, felony or misdemeanor, when the offense is committed in the presence of the person making the arrest or when they have immediate knowledge of its commission by the offender. In the second sentence, the statute additionally and separately authorizes that when the crime is a felony and the suspect is attempting to or actually escaping, the private person “may arrest him upon reasonable and probable grounds of suspicion” that the felony occurred and was committed by the person fleeing or attempting to flee.

As such, the statute provides for a lower threshold to arrest for felonies than for misdemeanors. Specifically, when the felony occurs outside of one’s presence and apart from one’s immediate knowledge, one can make the arrest when they have “reasonable and probable grounds of suspicion” that a felony was committed by a person escaping or attempting to escape. Why would Georgia allow for arrests of felons under this lower threshold? Because the state has deemed felonies to be much more serious than misdemeanors and the state has a more significant interest in detecting and punishing felonies than it does for misdemeanors. Georgia is basically saying, by this statute, that if you’re going to arrest someone for a misdemeanor (which are deemed not so serious by Georgia), the offense must be committed in your presence or immediate knowledge, but if your going to arrest someone for a felony (which it deems to be serious and which the state has significant interests in detecting, punishing, and deterring the commission of) then this lower threshold of mere “reasonable and probable grounds of suspicion” applies if the suspect is fleeing or attempting to flee.

In these regards, this statute wisely makes it easier to make a citizen’s arrest of someone when there is reasonable and probable grounds of suspicion they committed a felony and they are escaping or attempting to escape. By this statute, the state allows those committing felonies to be more quickly and easily detected, apprehended, and prosecuted. This is a very wise and sapiently written statute and is eminently reasonable. States have legitimate and compelling interests in detecting and preventing serious crimes and in apprehending and punishing those who commit such.

The statute’s words carry their plain meaning and the statute manifests an intent that the legislature wanted citizens and private persons to be able to easily detect and arrest those suspected of committing felonies when they are escaping or trying to escape. There is no ambiguity and this legislative intent must be given effect in interpreting, construing, and applying the statute. Although it obviously applies in criminal procedure, it is not a penal statute and does not prohibit or punish any crime, such that the typical rule of lenity (which requires that any ambiguity in penal statutes be strictly construed against the state in favor of the defendant) does not apply. However, it is a statute allowing for private persons to make arrests on behalf of the state. As such, any ambiguity must be construed in favor of the one making or attempting to make an arrest to give full effect to the statute and to protect the average citizens who are interpreting and relying on it in making arrests. Thus, any statutory ambiguity must be construed in favor of the Defendants, Mr. Greg McMichael, Mr. Travis McMichael, and Mr. Roddy Bryan. As such, the statute as written and interpreted must be construed in their favor to legitimize their arrest or attempted arrest of anyone they reasonably suspected of committing a breaking and entering or grand larceny (felonies under Georgia law) when such suspect was escaping or attempting to escape, such as Mr. Arbery was when he was running away down the road after illegally entering a property that did not belong to him and while under reasonable suspicion of having stolen goods from such property. It does not matter whether their reasonable suspicion was correct in hindsight, but only whether it was reasonable in light of the information available to them at the time of attempting to arrest Mr. Arbery. It was reasonable for them to arrest him and they had reasonable and probable suspicion to do so udner the facts and circumstances. I think Mr. Arbery was being hostile, mean, and foul toward them when they tried to speak with him to investigate what happened. People are allowed to follow and question whoever they want on public lands and property, such as the street in their community. Journalists do it all the time. The person does not have to answer, but they are still allowed to do so. If the person becomes belligerent or hostile in response, they should not be on public property where citizens are free to approach and question them about anything they want. They do not have to answer, but citizens are still free to approach and question them.

That was my thought, too, on the two sentences.

However, does not arrest imply restraint of someone who would otherwise walk away? That is, escape? Does anyone just hang around after committing a crime that you saw them do, and just say “Sure, I’ll go to jail”?

I suppose there are some circumstances (a justified shooting, maybe) but would they have been foremost in lawmakers’ minds when they wrote that?

Why does this matter?

Arbery was never arrested for his trespassing/burglary, or anything else that day, and their pursuit of him ended before arbery ran back to them. If the attempted arrest was unlawful, it had no direct bearing on the moment of the shooting, since they were no longer pursuing arbery or trying to detain him.

Travis didn’t use his gun against arbery to arrest him, but to ward him off, to defend against a battery, and to keep arbery from wresting the gun from his control.

Even if they had truly called off their pursuit, had they effectively communicated this fact to him? Should he have known that he was no longer in danger from them? If not, and if the pursuit was unlawful to begin with, then under the Wisconsin law we learned last week they would not have regained their innocence and the right to defend themselves. GA law may well be the same.

They communicated their lack of pursuit by not pursuing, but he came back, making him the pursuer.

I don’t agree that that is a sufficient communication that they’d ceased their attempt to apprehend him. He had no way of knowing (and indeed we have no way of knowing) that they didn’t intend to resume the pursuit.

Wisconsin law isn’t applicable in GA.

The statute clearly desks with two different situations The court failed To make that critical distinction

Sorry, but I have to drop the turd in the punchbowl here:

“The jury has the right to judge both the law as well as the fact in controversy.” — Chief Justice John Jay, 1789

“The jury has the right to determine both the law and the facts.” — Justice Samuel Chase, 1796

“The law itself is on trial quite as much as the cause which is to be decided.” — Chief Justice Harlan Stone, 1941

This is the theory of “jury nullification,” which every professional in the courtroom covertly acknowledges, but Dare Not Speak Its Name because it disempowers “the System.”

Briefly, it states that the jury reserves the right not to apply a law they believe is unjust, though only in the direction of acquittal, not conviction. It is one of the reasons juries are provided as a right, rather than having judges judge everything — the jury acts as a circuit-breaker against state oppression, including oppressive laws. In the US, its most popular use was by abolitionist juries who refused to convict defendants under the Fugitive Slave Act.

Here we have an example of what happens when a jury is not informed of this right (in Maryland this instruction is mandatory). They now have a law before them that badly needs judging, but they are kept unaware that they have the power to judge it.

You’re saying literally what Branca is. The state or the judge cannot give an ambiguous reading of the law to a jury without instruction that any ambiguity is to the benefit of the defense.

“Briefly, it states that the jury reserves the right not to apply a law they believe is unjust”

Not really. He is saying the jury makes the law and may decide whatever is desires regardless of any plain or convoluted meaning of the law.

I accept this interpretation. The jury of your peers is both a check on government mendacity and to uphold the sensibilities of the community if the law otherwise fails.

This notion makes the jury patently arbitrary. And so it is in real life. The jury is your judge. The judge is keep the process orderly, and ensure fairness in presentation by the parties in conflict. Otherwise, the jury made decide whatever it desires. This is why you never want to find yourself in front of one.

Reading the two statutory provisions together, as one must, I hold that the first sentence authorizes a person to make an arrest for any offense, felony or misdemeanor, when the offense is committed in the presence of the person making the arrest or when they have immediate knowledge of its commission by the offender. In the second sentence, the statute additionally and separately authorizes that when the crime is a felony and the suspect is attempting to or actually escaping, the private person “may arrest him upon reasonable and probable grounds of suspicion” that the felony occurred and was committed by the person fleeing or attempting to flee.

As such, the statute provides for a lower threshold to arrest for felonies than for misdemeanors. Specifically, when the felony occurs outside of one’s presence and apart from one’s immediate knowledge, one can make the arrest when they have “reasonable and probable grounds of suspicion” that a felony was committed by a person escaping or attempting to escape. Why would Georgia allow for arrests of felons under this lower threshold? Because the state has deemed felonies to be much more serious than misdemeanors and the state has a more significant interest in detecting and punishing felonies than it does for misdemeanors. Georgia is basically saying, by this statute, that if you’re going to arrest someone for a misdemeanor (which are deemed not so serious by Georgia), the offense must be committed in your presence or immediate knowledge, but if your going to arrest someone for a felony (which it deems to be serious and which the state has significant interests in detecting, punishing, and deterring the commission of) then this lower threshold of mere “reasonable and probable grounds of suspicion” applies if the suspect is fleeing or attempting to flee.

In these regards, this statute wisely makes it easier to make a citizen’s arrest of someone when there is reasonable and probable grounds of suspicion they committed a felony and they are escaping or attempting to escape. By this statute, the state allows those committing felonies to be more quickly and easily detected, apprehended, and prosecuted. This is a very wise and sapiently written statute and is eminently reasonable. States have legitimate and compelling interests in detecting and preventing serious crimes and in apprehending and punishing those who commit such.

The statute’s words carry their plain meaning and the statute manifests an intent that the legislature wanted citizens and private persons to be able to easily detect and arrest those suspected of committing felonies when they are escaping or trying to escape. There is no ambiguity and this legislative intent must be given effect in interpreting, construing, and applying the statute. Although it obviously applies in criminal procedure, it is not a penal statute and does not prohibit or punish any crime, such that the typical rule of lenity (which requires that any ambiguity in penal statutes be strictly construed against the state in favor of the defendant) does not apply. However, it is a statute allowing for private persons to make arrests on behalf of the state. As such, any ambiguity must be construed in favor of the one making or attempting to make an arrest to give full effect to the statute and to protect the average citizens who are interpreting and relying on it in making arrests. Thus, any statutory ambiguity must be construed in favor of the Defendants, Mr. Greg McMichael, Mr. Travis McMichael, and Mr. Roddy Bryan. As such, the statute as written and interpreted must be construed in their favor to legitimize their arrest or attempted arrest of anyone they reasonably suspected of committing a breaking and entering or grand larceny (felonies under Georgia law) when such suspect was escaping or attempting to escape, such as Mr. Arbery was when he was running away down the road after illegally entering a property that did not belong to him and while under reasonable suspicion of having stolen goods from such property. It does not matter whether their reasonable suspicion was correct in hindsight, but only whether it was reasonable in light of the information available to them at the time of attempting to arrest Mr. Arbery. It was reasonable for them to arrest him and they had reasonable and probable suspicion to do so under the facts and circumstances.

I think Mr. Arbery was being hostile, mean, and foul toward them when they tried to speak with him to investigate what happened. People are allowed to follow, investigate, and question whoever they want on public lands and property, such as the street in their community. Journalists, private investigators, and researchers do it all the time. The person is not required to answer anyone approaching and questioning them, but citizens are still free to approach and question them on public lands, properties, and roadways.

A person is not free to approach and question people about a crime while pointing guns at them. You seem to overlook that part.

When the pointing of the guns results in an unexpected response that causes the death of a person, then the citizens pointing the guns to begin with are responsible. For example in a negligence situation, it is a foreseeable consequence of pointing a gun at a person that said person will try to defend themselves by a means that may not seem logical or prudent. If death results, the death is a foreseeable consequence and the gun pointers are responsible for the death.

I mostly like your plain reading of the statute analysis but you go off on the wrong track a bit when you fail to recognize that the second sentence doesn’t apply to ALL or ANY felony. It specifically applies ONLY to WHEN may a citizen pursue someone to make an arrest. The negative implication of the second sentence is that ANY PURSUIT not authorized by the second sentence is forbidden to non-police officer citizens.

Think of it this way. The first sentence does NOT authorize a citizen to pursue and arrest someone under ANY circumstances. The second sentence merely carves out a limited exception to the first sentence that authorizes a citizen to pursue and arrest a fleeing felon. But the first sentence is still a limiting condition that applies to both the first AND second sentences.

“A person is not free to approach and question people about a crime while pointing guns at them”

Sure they are, but in this case they did not.

I was on a DUI jury in California in 1991. We were instructed that if we were convinced beyond a reasonable doubt of the defendant’s guilt, we “may, but need not” render a verdict of guilty.

I had heard of jury nullification before then, and took notice. but we went ahead and convicted the defendant once we decided the prosecution had proved its case..

Henry makes the point that I was going to make.

In fact, I’d say the average jury is better at reading and interpreting the law than the average judge or lawyer.

Better or not better at it, it is only meet and just that people of the average mentality of those expected to obey a law as written, get to decide what the proper interpretation of it is. Always keeping in mind that any ambiguity encountered must be resolved on the side of acquittal rather than conviction. If the legislature complains that they meant their laws to be interpreted differently, then they need to learn how to write them differently.

In a Civil War era statute, “within his immediate knowledge” would have to mean some sort of hearsay, correct? It could not possibly be a call from the store security video feed room watching the security feed to the security guard on the store floor, as the prosecution suggested. More likely, it’s news from the guy of horseback, hours, days, or even weeks later.

The phrase “immediate knowledge” deals not so much with the content or substance of the information and knowledge, but with the timeliness of it. “Immediate” in this sense means that the knowledge/information was recently obtained and was not remote, stale, or old. This “immediate knowledge” phrase served the state’s interests in quickly apprehending and punishing those suspected of criminal activity.

“Immediate knowledge” would include a scenario where one in a store security room watching the security video feed calls the security guard on the store floor and tells them a crime occurred and was done by so and so, and the guard then and there goes and arrests them. However, this “immediate knowledge” would not be satisfied when the call occurred weeks, months, or years ago and the guard makes the arrest weeks, months, or years later. In this scenario, the knowledge/information is no longer “immediate” in the temporal sense and is stale and old.

“Immediate knowledge” includes information obtained within the past few hours or at most 1-2 days. At the time the statute was enacted in the 1800s, this phrase was used to allow citizens to make arrests of persons in their local communities and abroad when they had information/knowledge that was fresh and timely, and indicated a person recently or just committed a crime. For example, an assault occurred on Side A of the town. The victim immeditately goes to Side B of the town (perhaps where the victim’s relatives are) and immediately tells them of such crime and of the offender, and such information was shared within merely 1-2 hours of the crime. Such citizens now have “immediate knowledge” that a crime occurred and of the offender and may go to Side A to seek and arrest the offiender. If the victim waits days or weeks to tell of such crime and offender, the knowledge is no longer immediate. Further, if the vicitim’s relatives wait days or weeks to make such arrest, the knowledge is no longer immediate. “Immediate knowledge” loses its immediacy incrementally with the increased passage of time.

Notwithstanding other uses of these terms in the 1800s, the construction “in his presence or within his immediate knowledge” suggests to me that “immediate” relates to degrees of separation rather than time. “Presence” implies direct observation, therefore “immediate knowledge” implies something just short of direct observation rather than something recently learned. So if Smith kills Jones in the saloon, runs off to fight the Yankees for a year, returns home and is spotted by Rusty, who though not a witness to the shooting knew about it from the bartender and Jones’ brother who were themselves witnesses, then Rusty is empowered to arrest Smith under this statute. Rusty would not be so empowered if he lived in the next town and had merely read about the shooting in the newspaper.

The time limitation is implied in the statute due to the arrest power being connected to crimes committed in someone’s presence (suggesting the arrest would occur right then) or a criminal fleeing a felony (suggesting the crime had just been committed). But this limitation is not clearly stated and so Smith might be reasonably subject to arrest one year after the killing of Jones.

If you want a good laugh watch this: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8eJ5E_-GUGY

Andrew, you would have an easier time understanding the Georgia statute if you noticed that the second sentence is NOT about all felony citizen arrests. It is limited to one specific fact situation. It clearly ONLY applies to the question of WHEN is a Citizen authorized to pursue and apprehend a criminal. It does NOT apply to all persons whenever and wherever situated who are suspected of having committed a felony at some time in the past.

It literally ONLY applies to WHEN is a citizen authorized to pursue and arrest a fleeing felon.

You talk about public policy, and express you don’t understand what public policy purpose is served by the second sentence if the requirements of the first sentence still apply to the facts of the second sentence. The answer is quite easy.

The public policy is that the State of Georgia didn’t want to authorize non-police officer citizens to investigate crimes, detain and question witnesses, etc for ANY felony no matter how old or remote in time to the citizen making the investigation, pursuit, and citizens arrest.

They clearly wanted citizens to be barred from doing “investigative police work”. Instead they use the second sentence to make it clear that the ONLY time a citizen is authorized to pursue someone to make a citizen’s arrest is when the offense is a felony and the perpetrator is attempting to escape the immediate scene of the crime.

In order for the second sentence to not be so broad as to include ANY Felony committed at any time no matter how remote in the past, the second sentence is subject to the limiting conditions of the first sentence.

That is the crime must have been committed in the presence of or within the immediate knowledge of the citizen AND the perpetrator must be trying to escape the immediate scene of the crime.

Well then you ask why does the second sentence mention reasonable grounds and suspicion that the person being arrested is the perpetrator. That is simple. That’s required for the “immediate knowledge” situation. If Citizen comes around the corner and sees Bill on his knees over the apparent lifeless body of Andy; and Andy has a knife sticking out of his chest; and Andy is still bleeding; and Bill has blood on his hands and torso. Then Citizen doesn’t “know” that Bill stabbed Andy because he didn’t see it, but he has reasonable grounds and suspicion to believe Bill stabbed Andy and that knowledge of reasonable grounds and suspicion is immediate in time to the physical scene and actual commission of Andy being stabbed. Therefore, if Bill sees Citizen and gets up and starts running away, then in that specific situation Citizen is authorized by the second sentence to pursue and arrest the fleeing felon.

I’ve elaborated on this example in greater detail here:

https://legalinsurrection.com/2021/11/arbery-case-verdict-watch-day-1-jurors-have-begun-deliberations/comment-page-1/#comment-1233342

It seems quite reasonable to assume that there is a clock on citizen’s arrest situations, certainly.

Your reading is not entirely convincing though. What does “citizen’s arrest” actually mean as opposed to pursuit? More specifically, if you see someone trespass how do you arrest that person? If the perp has just crossed the border with both feet the trespass is over: can you arrest him or is that “pursuit” already? If you said “you are under arrest” or some other magical words while he is still committing the trespass, does that change anything?

I am not sure, as I did not watch the entire trial and basically only followed the opening statements and the closing arguments: to me, it would seem the predicate felony is the presumed burglary committed in broad daylight on the day the events unfolded and the “burglary” a couple of nights prior is only one significant piece of the picture that constitutes the probable cause here.

The McMichaels still may have acted without probable cause and that might make all the difference. However, I got the impression that the prosecution did its best to muddy the waters and pretend that they attempted a citizen’s arrest for that nighttime burglary a couple of days prior to this tragic event.

I do not think that contradicts what Mr. Branca said, though.

“Why is that? Because under the legal doctrine of lenity, when a criminal statute is ambiguous, that ambiguity is always to be resolved in the favor of the defendant, never in the favor of the State. ..”

I think this “doctrine” is more in the nature of a suggestion than an absolute rule. Judges can and do ignore it when they don’t like the results. Anyway it is unclear how it applies in this case. Suppose Arbery had pulled a gun and killed Travis McMichael and was being tried for murder and was arguing the “arrest” was illegal. Then resolving ambiguity in favor of the defendant would point the other way.

Yeah, it would. And this all leads back to Wisconsin legislators not knowing how to legislate. If they had legislated clearly, there would have been no ambiguity to exploit, and therefore, no swinging-door exceptions.

Georgia.

Yes, it would. And if they were both alive, and both being charged somehow, then at each one’s trial the law would have to be interpreted in their favor. Why is that a problem? The fact remains that at this defendant’s trial the ambiguity must be resolved in his favor.

It’s ridiculous.

No, it’s designed to pass the buck. If the jury screws it up, then it’s up to an appellate court to fix it, and the rioters don’t burn down MY house. Even before rioting became the norm, they didn’t want to be the guy cited in legal textbooks as the one who got it wrong. And the attorneys go along with it because they want that opportunity for appeal.

I disagree with the writer (at my peril, I know), and here’s why: there was no probable cause.

If a police officer had seen what the defendants saw and went to a judge to get a search warrant, much less an arrest warrant, the judge would have laughed him out of chambers.

Even under the writer’s construction of the ambiguous statute – which I think is sound – the observed behavior of Arbury doesn’t amount to “probable grounds of suspicion”. How many of you have gone in daylight into an empty construction site to take a look at the structure’s layout and workmanship? I do it regularly in my neighborhood, and wouldn’t think twice about doing it elsewhere if there were something about the house that struck my interest. Legally cognizable probable cause to think I’m a suspect in a prior theft/burglary? No.

That’s my take with what’s been presented. I need to look at the common law of citizen arrest to see if there’s anything there that might have led the GA legislature to write something so foggy, though.

I think it is foggy because it was written in 1861 and it was the first time.

What was the deal with four different counts of murder on each defendant? There was just one guy who died.

I don’t question their guilt, video is a helluva bit of evidence. It saved Kyle Rittenhouse.

They can raise a count of felony murder for each felony charged.

Clearly the jury instructions on citizens arrest were not clear and may provide a basis for appeal However this did not appear to be as open and shut case of self defense as Rittenhouse and the three defendants did not come across well to the jury which heard the evidence

While I don’t know enough about Georgia law to know which construction is correct, I agree 100% that the judge not making the call on the interpretation of an ambiguous statutes was a monumental error, likely motivated by simple cowardice on the judge’s part.

Andrew, did the defense adequately object to the lack of instruction, tender an instruction in substantially correct form, and/or do whatever else was necessary under Georgia law preserve error on this point? If so, I agree that defendants have a decent shot at a new trial. If not, I doubt that it rises to the level of fundamental error.

I understand how the the law is ambiguous and the jury instructions flawed.

However, what I don’t see is how any interpretation of the law would lead the defendants to reasonably believe they had a right to make a Citizen’s Arrest.

They clearly stated they witnessed no crime. First time they saw him that day he was on a public street. And what possible probable cause could they have to believe he was escaping or attempting to escape after committing a felony.

Harmless error.