Has there been an increase in suicides and murders by young people?

What the statistics show

Reading reports of so many high-profile murders by teenagers, it’s not unusual for people to assume that there’s been a big increase in killings by young people, both murder and suicide. But statistics tell a much more complex story.

To the question of whether there been a rise in teen suicide, the answer is both yes and no (the following quotes are from an article dated November 2017):

An increase in suicide rates among US teens occurred at the same time social media use surged and a new analysis suggests there may be a link.

Suicide rates for teens rose between 2010 and 2015 after they had declined for nearly two decades, according to data from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Why the rates went up isn’t known.

The study doesn’t answer the question, but it suggests that one factor could be rising social media use.

So for two decades suicide rates had been declining among teens, and now there’s a recent uptick. Not only can the recent uptick not be explained, but I would guess that the previous two-decade decline cannot be fully explained, either. But how many people were even aware of that decline? And as for the recent uptick, does it even begin to compare with the high figures from decades ago?

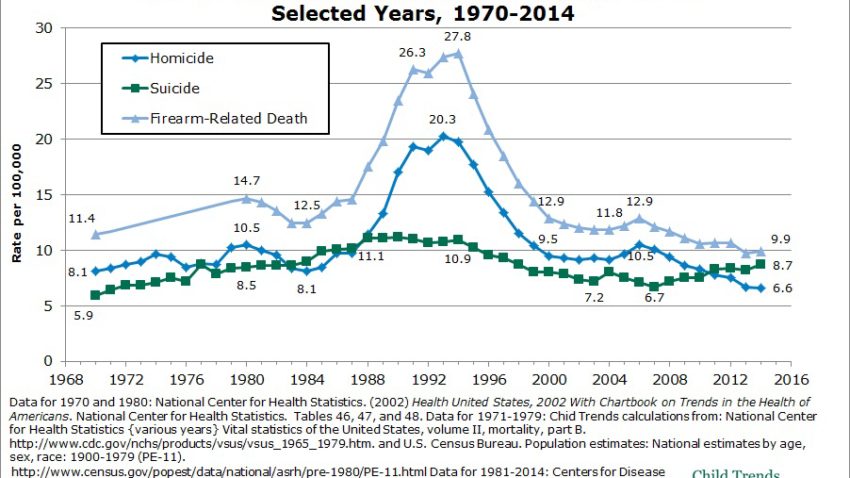

An organization called Child Trends tracks those statistics, and here’s a chart that shows suicides and homicides by teens aged 15-19 (as well as teen victims of homicides) from the 1970s to 2014, which should include most of the years involved in both the downturn and then the recent increase:

It’s apparent from the chart that the rise and fall in suicides was small compared with that for homicides. What was going on with homicides and gun deaths from 1988 through the mid-1990s? People can generate theories—and social scientists certainly have—but no one knows.

One leading and popular theory is that the widespread use of antidepressants was a highly contributing factor, but research is inconclusive:

While obviously concerned that it is possible that SSRIs may actually cause violent behavior in a small minority of people, [the study’s authors] fully recognize that other explanations are possible. These include the possibility that what is driving the violent behavior is medication undertreatment, based on the finding that the risk with violence was only found among individuals who were likely taking subtherapeutic doses. As reported by MedScape, one of the study authors, Seena Fazel, states: “Our own view is that some evidence suggests that it’s a bit more complicated than that, because we found a link with subtherapeutic doses of SSRIs, and that would suggest to us that it may be that it’s actually a lack of treatment [and] it could be residual symptoms that are driving this link.”

As for the line on the above chart for suicides, the suicide bulge for those years was much much smaller and more gradual than that for homicide, followed by a gradual decline in suicides and then another slight upward climb that hasn’t reached the previous levels. Note that the chart only applies to teens between 15 and 19 years of age.

It seems to matter which age groups are being discussed, because confusingly enough it turns out that for the ages of 10-24 suicides actually declined during that same period roughly corresponding to the 1990s:

Before 1990, youth suicide rates in the U.S. had increased over the course of several decades. The rates were said to have tripled between 1953 and 1957 and between 1983 and 1987, rising from 2.46 to 9.64 per 100,000 persons 15 to 24 years of age; however, the increase might not have been as great as was initially believed, owing to a possible undercounting of youth suicides.7 Starting in 1990, however, the suicide rate in the U.S. among youths and young adults between 10 and 24 years of age began declining steadily, falling from 9.48 to 6.78 per 100,000 persons between 1990 and 2003.8 Yet between 2003 and 2004, the suicide rate increased by 8%, to 7.32 per 100,000—the largest single-year increase since 1990.

Here’s what that author has to say (in 2009) about the effect of SSRI prescriptions on the phenomenon:

It may be no coincidence that the long decline in youth suicide rates in the U.S. began soon after the start of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) era, which started in 1987 with the introduction of fluoxetine (Prozac, Lilly)…

In many countries, a correlation has been found between increases in prescriptions for newer antidepressants and decreased suicide rates. However, the experience has been the opposite in Iceland and Norway, where suicide rates have risen or have remained unchanged even as antidepressant prescribing increased substantially. None of these studies establish a causal relationship between antidepressant use and suicide rates, of course, and many other factors can affect suicide rates…But the preponderance of the ecological evidence points to a potential protective effect for antidepressants with respect to suicide…

In the U.S., concerns about antidepressants led the FDA in 2004 to require the addition of a boxed warning to the labeling of these medications. This warning mentioned an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in association with the use of antidepressants in pediatric patients…

…Recently, however, concern has grown that instead of promoting the monitoring of patients who initiate antidepressants, these well-intentioned actions have had unintended consequences: underdiagnosis and under-treatment of depression in patients of all ages and increased suicide rates in young people, following years of steady decline in the suicide rate.

So far it’s really not clear what’s going on. It’s possible that different age groups and populations of young people respond differently to SSRIs and to current stressors, for example.

The decline for youths was part of a more generalized drop in murders that started sometime during the 1990s and has largely held to this day, a decline for which many theories have been advanced but has defied explanation. Americans seem largely unaware that the drop has even occurred:

Government statistics show that, except for some small blips, serious crime has decreased almost every year from 1994 through 2013. For over a decade Gallup has found that the majority of Americans polled believe crime is up, contrary to the fact that crime rates have plummeted in almost every small and large city since the 1990s.

Perceptions don’t appear to have caught up with reality.

[Neo-neocon is a writer with degrees in law and family therapy, who blogs at neo-neocon.]

Donations tax deductible

to the full extent allowed by law.

Comments

This caught my eye. But having suffered a suicide in the family two years ago, I usually still can’t bring myself to read about the topic.

I’ve come to accept that I’d only be guessing to think I might be able to piece together and understand what my little sister was going through in her mental state at the time.

Suicide leaves a hole in the loved ones left behind. I still feel drained of energy most days since it happened and I find it hard to find meaning in things I did before. I was a political junkie before, but now I don’t pay nearly as much attention to politics.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but in America I believe white males are disproportionately prone to suicide. It must be all the privilege.

Sorry for your loss. It’s horrible.

Interesting reading, for some insight into the suicidal mind:

The Role of Narcissism and Anger in Suicide:

https://drgeraldstein.wordpress.com/2015/04/05/the-role-of-narcissism-and-anger-in-suicide-understanding-germanwings-and-other-tragedies/

I have missed you. Now I know why.

The suicide rate remains pretty stable over the decades since the 1950s. The homicide rate, especially the firearm homicide rate, from 1987 through 1998 closely mirrors the usage of crack cocaine in the US.

Once again we have the problem of using age ranges without context, and conflating suicide and homicide numbers as if they bear any relation. While 15-19 year olds are “teens,” 18 and 19 year olds are adults, not kids. Lumping minors with legal adults ignores their differing rights and responsibilities.

In addition, when you look at the actual crime data, the majority of homicides in that age range (in every age range), even in the 15-17 yr old cohort, are teens with known histories of criminal and violent behavior or associations with others with such. Their risk of committing and suffering criminal violence bears zero relation to the risk of their peers who lack such histories and associations.

Simply put, violence is not evenly distributed within our society, a failure to recognize that makes any analysis useless for any policy purposes.

As for suicide, again the risk is not evenly distributed when you actually look at the data in detail, eliding those vital differences again leads to analysis without real utility.