Freddie Gray Trial: VERDICT WATCH

Jury deliberating fate of Officer William Porter

UPDATE (12/14/15, 5:39PM): Jurors dismissed for the day, back to deliberations at 8:30AM tomorrow.

UPDATE (12/14/15, 5:22PM): Both prosecution and defense agree with Judge Williams that no additional legal definitions will be provided to the jury.

UPDATE (12/14/15, 5:11PM): Jury asks for legal definitions of “evil motive,” “bad faith” and “not honestly.” That doesn’t bode well for a conviction. Hard to get a unanimous jury verdict on a charge if the jurors aren’t even sure they understand what the required elements mean.

UPDATE (12/14/15, 5:09PM): Jury asks for transcripts of radio recordings and of Porter’s interview. Those transcripts were never introduced into evidence, however, but merely used for demonstrative purposes. Judge Williams declines to provide them.

Today the jury in the “Freddie Gray” trial of Baltimore Police Officer William Porter was instructed by Judge Barry Williams, both the prosecution and the defense made their closing arguments, and the jury began their deliberations. Keep your eyes here for breaking news on a verdict.

Nothing I saw today served to change my opinion that, legally speaking, the defense was in far the superior position, and that indeed it appears most likely that not only did Porter do nothing illegal, he did more than he need have. Of course juries are unpredictable.

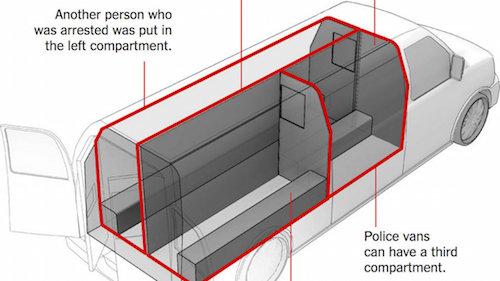

Officer Porter on trial for involuntary manslaughter, second-degree assault, misconduct in office, and reckless endangerment following the in-custody injury and later death of local community drug dealer Freddie Gray. Gray had suffered an 80% cleavage of his spinal cord while traveling in a police van after being arrested, from which injury he would die some days later.

An additional five Baltimore Police Officers face similarly serious charges arising from the incident, all of whom are scheduled to stand trial in coming weeks.

This post is based largely on today’s tweets by Justin Fenton (@justin_fenton) and Kevin Rector (@RectorSun), two journalist for the Baltimore Sun observing the trial live.

Jury Instructions

As has been typical of the lack of transparency of this case from the initial charges, the actual jury instructions do not appear to have been released to the public, so we’re limited to what we can learn from the tweets of reporters.

Judge Williams told the jurors “You should not be swayed by sympathy, prejudice or public opinion.” He also told them that while it was permissible for them to change their opinion upon convincing argument by the other jurors, they should “not surrender you h honest opinion.”

He reminded the jurors that the burden of proof remains with the State, and that they are duty bound to apply the law as he instructs them.

Williams also referenced Porter’s early statements to police, and told the jury that if they believed the statements were not voluntary they must disregard them. This refers to an unusual rule of evidence with regards to police officers.

Most suspects charged with a crime cannot be compelled to testify, and can simply plead the 5th Amendment and assert their right to silence. Police officers are in the relatively odd situation that if they are interrogated by their own department they might be fired if they refuse to cooperate with the investigation. In the eyes of the law such cooperation is deemed “compelled” by the implicit threat of the loss of their job. While the law allows such compulsion to force the officer to testify in cooperation with the investigation, it also holds that testimony so obtained cannot be used in a criminal trial against the officer.

Williams instructed the jury that to find Porter guilty (presumably of the involuntary manslaughter charge) they must find that he had acted in a “grossly negligent manner,” been aware of the risk created to Gray’s life, and have departed from the behavior of a “reasonable officer.”

For the second degree assault charge, Williams instructed the jury that Porter must have acted with gross negligence, but says it is not required that Porter have actually touched Gray (so, a mere act of omission could be sufficient to support a verdict of guilty on this charge).

On the charge of misconduct in office, Porter must have “corruptly failed” to do his duty as an officer, and with “evil motive.” Mere error in judgment is not sufficient to support a guilty verdict on this charge.

Prosecution’s Closing Statement

Prosecutor Janice Bledsoe presented the State’s closing argument. She began by arguing the legitimacy of the notes taken by Detective Teel of an interview with Porter soon after Gray’s death. Teel had testified that Porter said Gray couldn’t breath at the 4th stop. (There were six stops altogether, counting the first where Gray was loaded in the van and the last at arrival at its destination.)

Porter himself had testified that Gray made this complaint at the 1st stop, not the 4th stop. It might seem odd that Porter would argue the complaint came earlier, as that would seem to raise the question of why Porter hadn’t sought medical aid for Gray sooner. In fact, the earlier complaint would be consistent with Gray being out of breath because of flight and non-compliance with the police, rather than as a result of trauma. It is also worth noting, yet again, that if Gray was able to tell Porter that he could not breath, he was clearly breathing.In addressing the testimony between Teel’s notes and Porter’s in court testimony, the State asks the jury to consider “who had the motive to be deceitful? It’s not Detective Teel. It’s Officer Porter.”

The prosecution argues that given (they claim) that Gray complained about an inability to breath at the 4th stop, the only way Porter should be permitted to shift to van driver Goodson the responsibility for the failure to call for a medic is if “those words didn’t happen.”

Prosecutor Bledsoe also suggests that in Porter’s initial statement he described putting Gray on the van bench “like an object,” and only claimed for the first time at trial that Gray was able to physically assist the lift.

At this point Bledsoe’s closing began to veer off into the hyperbole that invariably accompanies a legless prosecution.

For example, Bledsoe grabs her suit collar and pulls it to her mouth, as if it were a lapel mounted microphone, mimicking an officer making a radio call, and says, “I need a medic. That’s all it would have taken.”

This, of course, ignores the actual legal issues entirely. Had Porter known Gray had suffered a life-threatening injury, it’s quite possible he would have had a legal duty to call for medical care. The defense’s entire theory of the case, however, is that Gray did not even suffer his serious injury until the second to last stop of the van, and therefore could not have known of the injury until they arrived at their destination—where, in fact, they did call for medical care.

With reference to the prospect that Gray had faked his earlier “injuries” in an attempt to avoid being transported to jail—a narrative strongly supported by defense testimony of Baltimore police officers with experience processing prisoners at the jail, who often faked such injuries for this purpose—Bledsoe remarked “This ‘jailitis’ is a bunch of crap.”

At this point it seems clear that the Prosecution’s strategy in closing is to simply make Porter out to be a liar, arguing that “The only reasonable conclusion is that Officer Porter is not telling the truth.” This is a very difficulty strategy with police officers, who are often quite experienced in testifying credibly, unless one has clear and convincing evidence of the alleged lies. No such evidence appeared in this case. It is even more difficult when, as in this case, the officer’s testimony is so strongly corroborated, even if only circumstantially, by the testimony of so many other police officers.

With respect to the general orders to seat belt prisoners and call for medics, Bledsoe argued that Porter “knew what he was supposed to do.”

Bledsoe argues to the jury that Gray’s traumatic neck injury occurred between the 2nd and 3rd stop of the van. In fact, not even the State’s medical examiner was willing to narrow down to timing of injury to that degree, being willing only to claim that the injury happened between the 2nd and 4th stop. Even then, this was based on her speculation, as there is in fact no actual evidence of the injury incurring in that interval. Indeed, there was considerable evidence that it could not have occurred that early.

Referring to the 4th stop, by which time Bledsoe claims Gray was severely injured and that Porter knew this to be the case, “When Officer Porter failed to call a medic, when the van door closed, that wagon became [Gray’s] casket on wheels,.” Again, there is no evidence to support the claim that Gray had suffered his injury by the 4th stop, and considerable evidence suggesting he hadn’t.

Bledsoe added “Every caretaker knows that it’s dangerous to travel in a vehicle without a seatbelt on.” I guess she’s hoping that none of the jurors have every travelled on a bus, or subway car, neither of which typically has seat belts.

More histrionics now, as Bledsoe held up a seatbelt and clicked it shut, asking “How long does that take?” Again, this ignores the actual legal issue, which is whether Porter had a reasonable rationale for not making use of the seatbelt. Such a rationale was stated by Porter in his own testify and buttressed by the testimony of other police officers.

To address the point that several of the other police officers testifying for the defense had noted that they rarely saw a prisoner belted into a van, and never before the date of Gray’s injury, Bledsoe argued that on the reasonable officer standard “A behavior isn’t reasonable because everybody does it.” Actually, the fact that “everyone does it” does, indeed, suggest that a behavior is reasonable. People usually, not always but usually, act reasonably.

Bledsoe then set out to define manslaughter for the jury as a combination of reckless endangerment, negligent assault and disregard for human life. (In fairness, this is based upon a journalist’s tweet, so I do not know if this is actually how Bledsoe phrased the matter.)

Bledsoe then tells the jury he will step through though how Officer Porter disregards Freddie Gray’s life, and then begins stepping through Porter’s actions van stop by van stop.

Here Bledsoe goes theatrical: “With great power, comes great responsibility. You know who said that? Voltaire. And Spiderman.”

Pointing at Porter, Bledsoe told the jury that Porter had the “opportunity on four or five occasions to wield his power and save Freddie Gray. He abused his power. He failed his responsibility.”

In wrapping up his closing, Bledsoe told the jury the state was asking them to hold Porter “responsible for the oath that he took, for his job, and for being a human being.”

It’s not really possible to do a substantive analysis of a closing statement based on a reporter’s Tweets, but I can’t help but note an almost perfect absence of any referral to actual evidence, the exception to Detective Teel’s notes. It is notable that the Detective herself conceded to some errors in her notes when cross–examined by the defense

Defense Closing Statement

Defense counsel Murtha presented the closing statement for the defense, starting by telling the jury that the State must prove not just the factors that caused Freddie Gray’s death, but also that the defendant Porter was personally and specifically responsible.

Murtha noted to the jury that it’s “sometimes hard to set aside our emotions,” but reminded the jury that they had taken an oath to do exactly that.

Murtha also dove right into the relevant legal issues, emphasizing the reality of officer discretion, and recounting that in Porter’s various observations of Gray he had not believed that Gray was seriously injured.

The defense noted that the prosecution emphasized the requirement that officers call for a medic, and responded “You say medic, I say when and where.” This strikes to the core of the defense theory of the case, which was that Gray did not suffer his neck injury until after the second to last stop (as their medical experts testified), and thus the aid provided at the last stop was in fact the first opportunity to do so.

As all good defense counsel do, Murtha then stepped the jury through all the individual bits of doubt the defense raised with respect to the state’s case. The defense need merely sustain in the minds of the jury a reasonable doubt on at least one element of each criminal charges brought against Porter in order to achieve an across-the-board acquittal, so focusing the jurors’ minds on doubt is critical.

Murtha raised doubts about whether Porter had ever actually seen the updated general order on seat belts? Porter testified that he had not, and the State presented not one piece of evidence that he had.

Murtha argued to the jury that the prosecution “overlooked” essential legal issues of the case because of the “absence of evidence” on those issues, and argued that “The state is asking you to insert information.”

The defense also counter-attacked the State’s effort to impeach Porter’s credibility. “The state is attempting to attack the credibility of Officer Porter” but “external facts” support that he is telling the truth.

Murtha emphasized repeatedly the degree to which Porter had made himself available to the investigators of Gray’s death as well as to the jurors, who had seen Porter take the stand and testify on his own behalf, and subject himself to cross-examination in the process. “He had nothing to hide because he did nothing wrong.”

Murtha also noted that the State was never able to make a substantive dent in Porter’s testimony, and that the prosecution “never had an ‘ah-ha’ moment during cross-examination” of Porter, because Porter had explained his actions so clearly.

There’s no moment where Officer Porter says, ‘You got me.” Porter, Murtha noted, had done nothing but make himself available.

Murtha also aggressively attacked the State’s lack of evidence, and undermined what little evidence it did have, notably Detective Teel’s notes. He pointed out that Teel herself in her own testimony had conceded to errors in her notes.

He noted that there is “literally no evidence” as to when in the van Gray was injured, and that the state was merely speculating and asking the jury to “fill in the blanks,” continuing that “It’s astonishing and it’s scary, the state is asking you to make a judgment and decision based on speculation and conjecture.”

In particular, Murtha characterized the testimony of state witness medical examiner Carol Allan, who testified that Gray’s neck injury occurred between the 2d and 4th stop of the van, as “speculative theorizing,” which it most certainly was. Murtha argues that Allan could not be more specific with regard to the stops because she literally has no proof. “Take your pick as far as Dr. Allan is concerned. Is it stop 2? Stop 3? Stop 4?”On the State’s inability to show when Gray was injured, Murtha argued that this alone was sufficient to undermine their ability to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Porter’s actions (or, more accurately, omissions) caused Gray’s death.

On the issue of Gray allegedly being unable to breath, Murtha noted that Porter was “taking to him. He can tell that he’s breathing.”

Murtha also stepped through the very favorable testimony of the defense’s many witnesses, one by one, emphasizing all the other officers who testified that Porter’s conduct was that of a reasonable officer.

He also noted that the defense had brought to the stand a great many officers from the Baltimore police department to testify as to the reasonableness of Porter’s conduct, whereas the State brought only a single officer from the Midwest.

In characterizing the State’s largely evidence-free theory of the case, the defense argued “They’re stretching, they’re reaching. They want you to be emotionally disturbed and upset.” Murtha urged the jurors to keep in mind that they were tasked with making “a legal decision, not a moral, not a philosophical decision.”

Murtha reminding the jurors that the instructions they were read told them to not judge Porter’s conduct with 20/20 hindsight, and that a mere error in judgment is not sufficient to warrant a criminal conviction.

Finally, Murtha closed by noting that whatever the prosecution might say on rebuttal, “it doesn’t take away what is not present in their case. And that is evidence.” The jury has to find that Porter had “evil motive and bad faith” in order to convict, and that proof is just not there.

Prosecution Rebuttal

Prosecutor Schatzow handled to rebuttal for the State, and the gist of it appears to be lots of histrionics, and a central goal of convincing the jury that Porter is simply a liar (a difficult task, as already described).

He first pointed to Porter’s “callous indifference to human life,” and claimed that Porter was no lying about the facts. “Every time that he is stuck” on a contradictory statement “he now comes up with some new explanation.”

He argued that a truly reasonable officer, on seeing Gray first put into the van at the initial stop, would have asked “Why are we throwing him in there like a piece of meat?”

On the lack of an “ah-ha” moment during the cross-examination of Porter, Schatzow tells the jury “This isn’t a movie. We aren’t on television.”

Schatzow then stepped through each of the defense arguments and simply scoffed at them, but without actually citing contrary evidence. An example was the defense argument that it was van driver Officer Goodson, not Porter, who was responsible for Gray: “It’s almost laughable.”

And with that, the State’s rebuttal was concluded.

Jury Deliberations Begin

The court took a break until 2:15PM, at which time the case was handed over to the jury for deliberations.

As mentioned, it’s hard to do an analysis of closing statements based on reporter’s tweets, but I certainly didn’t see anything that would change my mind that the defense is in far the stronger position in this case.

–-Andrew, @LawSelfDefense

Attorney Andrew Branca and his firm Law of Self Defense have been providing internationally-recognized expertise in American self-defense law for almost 20 years in the form of blogging, books, live seminars & online training (both accredited for CLE), public speaking engagements, and individualized legal consultation.

“Law of Self Defense, 2nd Ed.” /Seminars / Instructors Course / Seminar Slides / Twitter /Facebook / Youtube

Donations tax deductible

to the full extent allowed by law.

![[Freddie Gray van]](https://c4.legalinsurrection.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Freddie-Gray-van.png)

Comments

Finally, Murtha closed by nothing that whatever the prosecution might say on rebuttal, “it doesn’t take away what is not present in their case. And that is evidence.”

I suggest “noting” in place of “nothing”.

But a mere typo in an otherwise excellent rendition.

The closing arguments were pretty much as expected.

The defense has the evidence and the law.

The prosecution has “spiderman” and BS.

Pretty much.

You know how it goes.

When you have the facts, pound the facts.

When you have the law, pound the law.

When you have neither, pound Spiderman.

Wait . . . that didn’t come out right. 🙂

–Andrew, @LawSelfDefense

LOL, that is exactly what I was thinking the Prosecutions closing arguments sounded like the literal definition of Pounding the table.

and histrionics and street violence and….

Seems like the state has failed to provide a compelling case, beyond a reasonable doubt.

In fact, there appears to be reasonable doubt just about everywhere.

Well, maybe the rioters and looters will have a chance to score some 5-finger discounts on merchandise just before Christmas.

‘Tis the season.

I’m sure the defense is worried that the Jury could be biased and influenced by riots and pre-trial publicity. I’m sure they are also worried of a compromise verdict where this poor defendant gets screwed over for something just because…

correct title would be riot watch…….

Prayers for Justice.

If there are any windows in the Jury room somebody might want to check and make sure that Mrs. Mosby isn’t on a ladder giving them dirty looks.

Is it even possible for her to give anything but a dirty look? Every pic I’ve seen of her is scowling, the only difference being one of degree.

The prosecution made a very good case

Unfortunately, they made it for the defense.

“Those transcripts were never introduced into evidence,”

This sounds like a major oversight on the prosecutions behalf, since Porters interview was pretty much what their entire argument hang on.

I doubt the transcripts of Porter’s interview were admissible.

Rules of evidence are not my particular area of expertise, but it’s my understanding that if a police officer is compelled to cooperate with a departmental investigation in the aftermath of a actual or alleged police-caused death, the results of that compelled participation can normally not be used against the officer in criminal court.

Otherwise cops would never cooperate with departmental investigations in such cases, and we want such cooperation. So, public policy reasons for the evidentiary exclusion.

Rule would be different if they’d criminally charged Porter and treated him as a suspect rather than a victim at the time of the interview, but then he wouldn’t have talked to them at all on 5th Amendment grounds (I hope).

–Andrew, @LawSelfDefense

Professor

I think you are referring to the Gilkey rule?

What I found amazing was that the judge allowed Porter’s statements to be admitted in the first place, then tell the jury to ignore them if they believed them not voluntary. Isn’t that reversible error? The judge decides the admissibility of evidence. He doesn’t admit evidence and then tell the jury to ignore it if they believe it is legally inadmissible.

Looking at what the jurors asked for more closely. I think we have made an mistake interpreting what the jurors asked.

Audio recordings of the police communications and I think a video recording of Porters interview were introduced. When the jurors were played these recordings the jurors were given transcripts ( for “demostration purposes” ). The transcripts are not evidence, the recordings they were made from are. Isn’t there some rule about best evidence? Also the transcripts are technically hearsay. They are statements of what the transcriber heard from the recording.

The jurors have to work with the recordings. I think they would rather work with transcripts because they are easier to search.

That jury is looking for a charge they can superficially hang their hat on with a straight face.

It’s the terrorism of BLM threats and riots that will convict in these cases, nothing more.

Just to keep hope alive, I would point out that in WA state, it is prosecutorial misconduct to call a witness a liar, or even imply that the witness was lying. Especially if the witness was the defendant. This is because lying under oath is a crime and therefore such an accusation is tantamount to telling the jury to convict him because we have other crimes we can charge him with.

Needless to say, in WA state it is reversible error. However, we only have reporter’s hearsay tweets to use here so YMMV.

Rule Of Optional Completeness—

When a writing or recorded statement or part thereof is introduced by a party, an adverse party may require the introduction at that time of any other part or any other writing or recorded statement which ought in fairness to be considered contemporaneously with it.

That’s an evidentiary rule that could explain your inquiry. It may easily be the prosecutors had more to lose than gain by attempting to use the transcripts.

Prosecutors are gambling. This is clearly the weakest case. If Porter is acquitted and there are riots, juries for the other five cases may be intimidated into bogus convictions.

If Porter is convicted of anything, some of the others may wish to plea bargain.

Only if Porter is acquitted and Baltimore is quiet does the prosecutor lose in this gamble.

There’s at least one other option, and that’s the judge…faced with “civil unrest” over this nothing case…revisits a change of venue.

The prosecutors have to know that all of these cases are crap. Remember the Trayvon Martin trial? It went so very badly that the protesters began turning on the prosecutors and claiming they were deliberately losing the case. I think that is the number one thing the prosecutors want to avoid here. So if you are highly likely to lose every case, it makes sense to start with the weakest case and a black defendant. That loss is more palatable to an angry group of protesters. It greases the political skids for future lost cases. At the end of the day, Mosby doesn’t want her own supporters attacking her.

Due to lack of substantial evidence, my prediction is “not guilty” on all counts. I don’t see any way that the entire jury can get over the reasonable doubt standard for any of the counts. However, it’s possible that there could be a hung jury on one or more counts but no convictions.

The more I learned about officer Porter during this trial, the more I came to realize that he is the kind of cop people in any city should want more of. He treats people including the lawbreakers with respect and gets his job done very peacefully. If it were not for Baltimore politics these charges would never have occurred.

Today a Chicago cop, Glenn Evans, was acquitted of charges that he shoved a gun down someones throat.

I’m sure Rahm is hoping for a quick not guilty verdict, so the riots can distract everyone from his troubles in Chicago.

@ Andrew

Are these standard questions that you get from juries? I mean asking for the transcripts is one thing, but asking for a definition of; “evil motive,” “bad faith” and “not honestly.”

Or is this a case of Juries being made up of people who weren’t smart enough to get out of jury duty?

I am now channeling Professor Trelawney. I divine that there are one or two holdouts for guilty who are hanging onto those words. They asked the judge for definitions to force the jurors to be faced with the truth.

It may be that they’re trying to rationalize a guilty verdict on one or the other lesser charges as a compromise between justice and social justice.

Developing a working understanding of the terminology is merely a first step towards analysis of the case. When insecure in their understanding of the terminology, jurors are very reluctant to convict for fear of making a mistake. An attempt to gain understanding, or even actual, real understanding itself, only means they’re trying to be fair and thorough. It does not indicate a bias towards the prosecution.

What this tells me is that at least some of the jury is strongly divided. People are asking for transcripts and definitions to use as evidence to bolster their own position during deliberations. Instead of having to argue with people’s memory of what they thought they heard and people’s beliefs on what those definitions are. It’s a smart move to “get the paper” that supports your position. Likely there is a large disparity of IQ and education levels on this jury. It can be very tiresome arguing with people who aren’t very smart. Definitive proof “on paper” cuts out a lot of unnecessary back and forth.

What could be taking them so long? Surely this is as slam-dunk a case as any could possibly be. It only took Shelly Silver’s jury about 5 minutes to convict him.

On the other hand, a few years ago when I was on a jury, we walked into the jury room and were in immediate agreement that the plaintiff had no case, but I insisted that precisely because we were all so sure, we owed it to the plaintiff to go over the evidence and look for something we might have missed, something that might indicate we were mistaken. So we spent 2 hours at it, and just became even more convinced that there wasn’t anything there, and the plaintiff had just wasted 4 weeks of everyone’s time trying to pin her misfortunes on the defendants, who as far as we could tell had done absolutely nothing wrong.

I have only been in one criminal trial, actually only on the one jury and it was for embezzlement. However, that being said, it took us a fair amount of time to just make our way through the instructions deciding who would be the foreman, which could have been all they got accomplished today. Also, we had a very good and organize foreman, which was of great benefit to us.

Allow me to note for the record that your jury’s behavior makes me proud of being American.

I’ll second that.

When I was on my first jury (of a criminal case), I thought that the jury room would be full of idiots – the brainless, the slothful, the uncaring, the distracted, the anxious. However, to my great surprise, I found them to be very serious about doing a good job and the right thing by the law and the defendant. They were focused, articulate, and took their responsibilities seriously. The entire experience gave me great confidence in the jury system (if not in the courts themselves).

Bledsoe remarked “This ‘jailitis’ is a bunch of crap.”

Isn’t this kind of stupid to say during closing?

Can’t any lawyer suing Baltimore for police misconduct use this in their trial?

I doubt that the Persecutor cares about the good of society or protecting the city from lawsuits. They only want to win so they will get street cred for sticking it to the cops.

“It is also worth noting, yet again, that if Gray was able to tell Porter that he could not breath, he was clearly breathing.”

Do you have any medical authority for this assertion? Doesn’t air only have to go out, not in, to speak?

Exhaling is also part of breathing. Breathe in, breathe out. — Dr. Char Char Binks, Esq.

Air can only be exhaled after being inhaled. The act of speaking is concrete proof that a person is breathing. As such, by the time you realize that you cannot breathe, it is too late to warn anyone via speech.

Generally, what most people mean when they say “I can’t breathe!” is that they feel unable to take a natural/ full/ deep breath. Which can be quite terrifying.

The only exception to the rule are “last words.” If you use your last breath to say something, they will be your last words.

Breathe in, breathe out. Repeat until dead.

I suffer from larnyxspasms( sic )??.Believe when you can’t breathe ,you can not talk and the first couple times, It scared the heck out of me . They last less than 1 or 2 minutes but are scary.

Sorry believe me when you can not breathe, you can not talk

Having been a juror, it is my experience that refusal to explain terminology and law to the jury engenders bad feelings against the state. Jurors feel that if the judge won’t explain something to them, then the state can go jump in a lake because it’s wasting my (the juror’s) time by not helping me get through this with due regard for the specifics.

Jurors are also less likely to convict when they are unsure of technical details that they’ve been asked to consider (whether they’ve been exhaustively explained or not). They don’t want to convict someone through a misunderstanding.

Mike Mcdaniel at his blog Stately Mcdaniel Manor has had an excellent series on the Freddie Gray saga , that agrees with Mr Brancas assessment and adds some other insights , you should check it out .

A few days ago a white criminal named Tyler Temperman shot a Maryland LEO in the face. He didn’t end up in a police van with his spine severed. He will have his day in court. But all is equal in the criminal justice system.

I’m glad you’re coming around.

Donta Allen was in the police van with him. “The second man inside the Baltimore Police transport van with Freddie Gray is disputing a report in The Washington Post that claimed he had heard Gray deliberately beating his head against the walls in a bid to injure himself.”

“Mr. Allen sought out WJZ in what he called an attempt to save his life from retaliation. The Post report said that it got the police document only on condition that it not name the second prison because he fears retaliation.”

It seems that he recanted after being threatened, no doubt by BLM thugs.

There has so far been no allegation that any policeman deliberately injured Grey, or did anything to cause Grey’s injury. What happened to Grey seems, based on all the information available so far, to have been either an accident or self-inflicted. So how can Temperman’s failure to have an accident or to injure himself possibly show anything about the police?

BTW Milhouse, just thought I would point out that it was Tyler Testerman… Testerman, who was arrested in that incident. Anyway, I agree with you, completely, these two incidents have in common.