Rape Culture Theory Ensnares Innocent Men

Many people hearing talk of America’s campus “rape culture” might be tempted to dismiss the overheated rhetoric as harmless.

Despite little evidence “rape culture” exists, though, three recent roundtable discussions on campus sexual assault hosted by Sen. Claire McCaskill (D-MO) showed that not only do some people absolutely believe a rape culture exists on college campuses, but the federal government is involved in policing the issue on campuses.

The Department of Education mandates colleges to handle every single student sexual assault through internal quasi-legal proceedings, in which the school performs all the roles of investigator, prosecutor, judge, executioner and statistics compiler.

From the perspective of accusers in campus sexual assault cases, they may very well prefer a quasi-legal adjudication of their complaints because it provides a much broader definition of sexual assault, a much lower burden of proof and an environment in which “student’s rights” tend to be accuser’s rights, with little emphasis on rights for the accused.

For the accuser, it makes the alleged post-assault experience that much less stressful.

From the accused’s perspective, though, he’s not gonna know what hit him.

Schools Play Law and Order: SVU

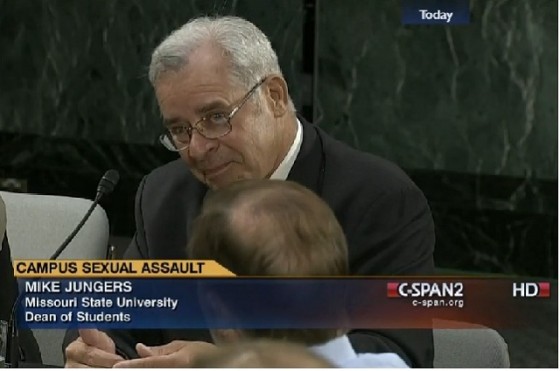

Speaking amongst friendly colleagues last Monday at the third roundtable, Mike Jungers, the dean of students at Missouri State University, made the surprising statement that new investigation procedures of campus sexual assault were resulting in the alleged perpetrators agreeing to be interrogated without obtaining an attorney.

He considered this to be a good thing.

“They used to lawyer up immediately, first thing,” Jungers said, with a laugh. “You know, you’re cut off from talking to your student—which drives me crazy—by an attorney saying, ‘This is my client, and…you don’t talk to him or her directly, you talk to me.’”

It drives him crazy if a student obtains legal counsel for questioning, as if an accusation of rape could be handled in an amicable fashion, with no concern that the system could go against him and result in the young adult having to register as a sex offender for the rest of his life—or alter the remainder of his college career and his college record.

The regular criminal justice system may also undertake the case, where he’d even be offered an attorney if he couldn’t afford one. But under the extensive Title IX investigation guidelines put out by the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) at the end of April, schools don’t have to contact law enforcement at all (unless their state or local law requires it).

If the school obtains forensic evidence in their investigation, the OCR merely states “it may be helpful for a school to consult with local or campus law enforcement or a forensic expert to ensure that the evidence is correctly interpreted by school officials.”

In fact, much is left up to the school’s interpretation, including defining exactly what “sexual assault” is.

This (Probably) Isn’t Your Grandmother’s Definition of “Sexual Assault”

The meaning of sexual assault is not what it used to be. As Jennifer Gaffney, the special victims deputy bureau chief of New York County’s district attorney’s office, said in the roundtable discussion, there is often a gap between the college definition and what they can actually prosecute under state statutes.

The panelists at McCaskill’s roundtable tended to accept a new definition of sexual assault in which a vague, unquantifiable sense of too much alcohol may not incapacitate the female but could make her less than able to fully consent.

The accuser may appear to be fully functioning and participating in the sex act, and therefore seeming to fully consent at the time. But she can later say that she was too impaired to have exercised good judgment and make her consent invalid, leaving her sex partner to be charged with sexual assault for an act he believed was consensual, where the woman had said “yes.”

The definition of “sexual assault” and its varied related terms, such as “sexual violence,” is one of the key battleground areas, and the types of offending behaviors may be about to be expanded even further.

McCaskill has been conducting these roundtables regarding campus sexual assault in advance of introducing legislation in August, which will also impose additional mandates on schools in regards to domestic violence, “dating violence” and stalking.

Michael Stratford of Inside Higher Education reported Tuesday that “McCaskill said that she is working with a bipartisan group of lawmakers in crafting the legislation, including Republican Senators Dean Heller of Nevada, Kelly Ayotte of New Hampshire and Marco Rubio of Florida.”

Note that the line is not being drawn at only changing the sexual assault definition at colleges. McCaskill also would like to see states adjust their legal standards to be more in line with the looser college definition. Last year, the FBI changed their definition of rape, part of which changed the phrase “forcibly or against the victim’s will” to “without the consent of the victim.” Some states are also changing or adding to their sexual assault statutes.

Katharina Booth, Boulder County chief deputy district attorney, said that the State of Colorado has an additional standard beyond “physically helpless” (that is, the accuser was asleep or unconscious). Under it, she can bring criminal prosecutions if the accuser meets the standard of “’incapable of appraising the nature of your conduct,’ which is going to encompass the bulk of what we see, which is the voluntarily intoxicated but not all the way at the passed-out stage. So we’re in that gray area,” she said.

An Alcohol Aside

The issue of alcohol consumption is a very touchy one in rape-culture activism.

No one wants a woman blamed for being sexually assaulted because she wore a skimpy outfit. Likewise, many fear a sexually assaulted woman will be blamed because of her drunkenness. It is common thinking that because no one should ever be sexually assaulted, no blame should ever be put on them.

Under the new sexual assault definition, though, a consenting woman can later claim (and have a charge initiated because) there was really no consent because she was too drunk.

Booth noted that incidences in which the woman is drunk beyond her ability to consent are the ones that “encompass the bulk” of the sexual assault cases she sees.

Studies have shown that the majority of unwanted sexual encounters experienced by collegiate women occurred when they were intoxicated. Yet the roundtable panelists adamantly rejected the suggestion that sexual assault prevention education should encourage reduced alcohol consumption.

As for the accused’s state of drunkenness, no one at McCaskill’s roundtable suggested that the man should have as a defense that he was equally too incapacitated to make good judgments.

In fact, take the case of Lewis McLeod. He is suing Duke University for expelling him for what he and the local police say was a false allegation of sexual assault.

Attending the trial, John H. Tucker of Raleigh-Durham’s Indyweek reported, dean Sue Wasiolek was asked in court whether both parties would be considered guilty of rape and thereby expelled if they engaged in sex while both were intoxicated to “incapacity.”

The dean responded, “Assuming it is a male and female, it is the responsibility in the case of the male to gain consent before proceeding with sex.”

In the new climate of sexual assault pseudolaw, the female apparently has no responsibility other than to say yes, which can be revoked anytime, including after the sex is over.

The Unburden of Proof

It’s not just their broad definition of “sexual assault” that makes college-adjudicated cases less likely to be prosecuted in the criminal justice system.

The minimal proof required by the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights—and therefore used for the national sexual assault statistics they collect and publish—doesn’t pass the much stricter burden of proof used by real-world prosecutors, judges and juries.

Forget the “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard of courtrooms and crime dramas. They’ve even decided the lower standard of “clear and convincing evidence” is too tough.

As KC Johnson of Minding the Campus puts it: “the Education Department’s Office of Civil Rights has mandated a lower threshold of certainty in sexual harassment and assault cases, from the clear-and-convincing standard (around 75 percent certainty) to the preponderance of evidence standard (50.01 percent).”

This means the school only has to find it’s a smidgen more likely than not that the crime occurred. Therefore, a college can convict someone of sexual assault much more easily than a criminal court could.

New Federal Guidelines Say Accused Don’t Need Constitutional Privileges

A college-adjudicated case of sexual assault also has no requirement to provide the alleged perpetrator the rights and protections he would receive in the real world. The government actually says he doesn’t need them.

OCR tells schools there is a distinct difference between a criminal investigation and a Title IX one (emphasis added):

A criminal investigation is intended to determine whether an individual violated criminal law; and, if at the conclusion of the investigation, the individual is tried and found guilty, the individual may be imprisoned or subject to criminal penalties. The U.S. Constitution affords criminal defendants who face the risk of incarceration numerous protections, including, but not limited to, the right to counsel, the right to a speedy trial, the right to a jury trial, the right against self-incrimination, and the right to confrontation. In addition, government officials responsible for criminal investigations (including police and prosecutors) normally have discretion as to which complaints from the public they will investigate.By contrast, a Title IX investigation will never result in incarceration of an individual and, therefore, the same procedural protections and legal standards are not required. Further, while a criminal investigation is initiated at the discretion of law enforcement authorities, a Title IX investigation is not discretionary….even if a criminal investigation is ongoing, a school must still conduct its own Title IX investigation.

That’s astonishing for the government to say a school investigation will “never” result in incarceration. Sure, the school can’t imprison the accused in its basement, but can the product of their interrogations and evidence collection never end up being used in a criminal court?

If the school does indeed find the accused guilty, the OCR does not require any appeals process. It permits a college to offer one if it so chooses, but only if both parties are offered the same opportunities.

For instance, the accused may appeal a punishment as being too harsh, but only if his accuser can appeal the punishment as being too lenient.

Currently, the OCR guidelines give schools wide discretion in deciding punishments. (That’s something McCaskill would like to make uniform—more one-size-fits-all sentences.)

They can expel him or merely force him to move to a different dormitory or a different school. They can restrict the places he can go on campus and the courses or extracurricular activities he can attend.

For instance, if the accuser has the same major as the accused, she may opt to take the courses she wishes, and he’d be required to take them at an alternate time or manner, such as online or by independent study.

In fact, many of these sanctions can be applied even before the investigation is complete in order to comply with Title IX’s mandate to make the accuser feel safe from further alleged harm and to prevent contact between them.

Someone ultimately found innocent by the school could suffer these penalties before that finding is reached. The OCR guidelines are silent on what a school should do to make restitution if that occurs.

Who Is a Good Guy in a Rape Culture Theory World?

It should go without saying, everyone wants rapists stopped and punished. But rape culture theory implies all men are potential rapists, and sexual intimacy under the influence carries the threat of being deemed sexual violence.

What’s a regular non-rapist guy supposed to do if he gets ensnared in the “rape culture” frenzy? Once a Title IX investigation begins, there is no telling where it will end for the accused. Yet he’s denied the Constitutional protections he would receive if he were speaking to the police instead of the school’s Title IX Coordinator. (That’s the person who’s supposed to be preventing sex discrimination.)

Some are advocating for upcoming legislation to include attorneys for both parties. The current OCR guidelines don’t preclude that, but do state that schools can limit the parts of the proceedings an attorney can participate in.

Teresa Watanabe of the Los Angeles Times wrote, “At present, campuses vary in policies on attorneys — the University of California allows them but Occidental does not. Ruth Jones, Occidental’s Title IX coordinator, said the college has barred attorneys to prevent the discipline process from being too “adversarial” but would change the policy in accord with final federal regulations.” She wouldn’t have much choice, if it becomes the law.

It’s easy to see why school administrators like Jungers at Missouri State University find things run much more smoothly without an attorney clogging up the process with non-Title IX law.

The Department of Education gives him a suggested maximum of 60 days to get the whole thing investigated, adjudicated and punished so that he can get his report to them and they can add a tickmark to their campus sexual assault statistics. If he’s slow in getting his results, or if the accuser doesn’t like the results, the feds can put his school under investigation and take away its federal student aid money.

The young man shouldn’t have any fear of that, right? The government and the school tell him he doesn’t need a lawyer, even if he’s being accused of what’s considered a felony outside the campus walls.

In an essay for Time last month, Christina Hoff Sommers, author of The War on Boys, vividly portrayed the problem facing male students in the “rape culture” environment:

On January 27, 2010, University of North Dakota officials charged undergraduate Caleb Warner with sexually assaulting a fellow student. He insisted the encounter was consensual, but was found guilty by a campus tribunal and thereupon expelled and banned from campus.A few months later, Warner received surprising news. The local police had determined not only that Warner was innocent, but that the alleged victim had deliberately falsified her charges. She was charged with lying to police for filing a false report, and fled the state.Cases like Warner’s are proliferating. Here is a partial list of young men who have recently filed lawsuits against their schools for what appear to be gross mistreatment in campus sexual assault tribunals: Drew Sterrett—University of Michigan, “John Doe”—Swarthmore, Anthony Villar—Philadelphia University, Peter Yu—Vassar, Andre Henry—Delaware State, Dez Wells—Xavier, and Zackary Hunt—Denison. Presumed guilty is the new legal principle where sex is concerned.

On campuses across the country, there’s actual rape and sexual assault by anyone’s definition. And there’s false accusations of it. And there’s “the gray area” in between. The Department of Education has decided to be the overseer of it all, with all schools receiving federal dollars given the impossible mandate of serving as its prevention and enforcement bureaus.

Many schools already feel overwhelmed with the new responsibilities. Still, in an effort to increase reporting of campus sexual assault, the government created a website for the accusers: NotAlone.gov.

The OCR claims it wishes to treat the accused with fairness and equity. For all the accused stripped of Constitutional rights and wondering if they do need an attorney, perhaps the government should create a DontBeAlone.gov site for them.

—————–

“Prudence Paine” is a pseudonym for a former journalist whose work has appeared on newsstands in national magazines. Her quest for knowledge has led to an excessive amount of time spent on college campuses. She can now be found writing a couple books, participating in the MOOC revolution (free online college classrooms) and tweeting at @prupaine.

CLICK HERE FOR FULL VERSION OF THIS STORY