Cyprus has been given more flaming hoops to jump through for its economic bailout.

BBC News Business is reporting that Cypriots will be asked to make further financial sacrifices:

The International Monetary Fund (IMF), which is contributing 1bn euros, says they are “challenging” and will require “great efforts” from its population.

They will mean a doubling of taxes on interest income to 30% and a rise in corporation tax from 10% to 12.5%.

…The plans for the two largest banks, Bank of Cyprus and Laiki, are especially controversial in Cyprus, as they will involve heavy losses for depositors with large balances in their accounts.

I noted in my last report that the restrictions on Cypriot bank transactions were to last 30 days. Interestingly, Iceland pioneered “temporary” capital controls in 2008.

Those controls are still in place….and are working out for Iceland about as well as expected.

The Icelandic capital controls have proven to be highly damaging for its economy; investment has collapsed and is just about the lowest in Europe at 14.4% of GDP in 2013, compared to the EU average of 18%. The reason is that foreign direct investment almost completely dried up and any domestic residents with money left over prefer to keep their funds liquid, ready to be exported when an opportunity presents itself. Domestic investment is not compatible with that objective.

While the capital controls are meant to prevent outflows of money, those wanting to take money out will find a way, legally or otherwise. The end result is a cat-and-mouse game between the government and capital owners, one where the authorities are at a disadvantage. This leads to ever-tightening of the controls. Meanwhile, the conditions are ripe for corruption, anybody with access to the licensing for capital exports stands to benefit. Having the central bank in charge of licensing for the export of capital, as is the case in Iceland and Cyprus, can only undermine its integrity.

Also, it is fascinating that after the Cyprus deal was struck, the stock markets reacted positively. This report is from CNN Money on March 25:

U.S. stock futures were higher ahead of the opening bell.

European markets rallied more than 1% in morning trading, while Asian markets ended mixed. After an initial bump, the euro was little changed against the dollar.

Grant Williams, the chief investment strategist for Mauldin Economics, offers an entertaining and cautionary analysis of Cyprus that includes this reminder about another 2008 event – the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy.

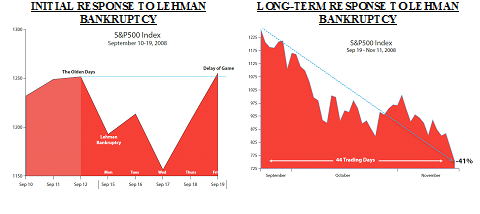

As you can see from this chart, by the end of the first week after Lehman crystallized everybody’s very worst fears, the market managed to close slightly positive, inducing a false sense of calm. However, that close above the pre-Lehman level was the last time the market would see such heady heights for quite a while.

The next chart…shows what happened in the two months immediately after that first-week close; and, as you can see, just because bad stuff didn’t happen in those first few days, it didn’t mean things weren’t about to get very, very dicey indeed as reality sunk in.

Plainly, all factors indicate that the warm Mediterranean island will soon share Iceland’s chilly economic future.

DONATE

DONATE

Donations tax deductible

to the full extent allowed by law.

Comments

Markets rose not so much because of what the IMF & Cyprus did to stabilize that economy, but because the Cypriot people are apparently going to simply take it without major disturbance. Had they rioted and had the government or bank system of Cyprus gone wobbly the story may have been quite different

It’s early, but getting late faster and faster, now. Let’s check back in three months.

Why do I keep seeing “Maudlin” instead of “Mauldin”? The former seems more accurate.

Unbelievably, he U.S. Government and Great Britain are considering doing the same thing as Cyprus did. Resolving Globally Active, Systemically Important, Financial Institutions From this FDIC document, Page 6 (Section 13):

Notice how the FDIC uses the word “creditors” for depositors? Technically, that is correct. When you deposit $1,000 in a bank, you no longer legally own the money; The bank gives you an IOU and you become a creditor. I think more and more people are starting to realize how this works.