N3v$r M1^d Those Crazy Password “Rules”: Four-word Passwords Hardest To Crack

There is also no need to change your password unless a threat is detected

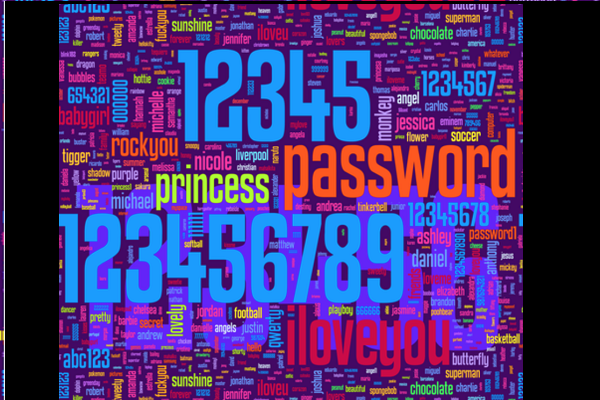

Back in 2003, Bill Burr wrote the primer on password development. His definitive work recommended random characters, letters, numbers, caps, casing, etc. in a mishmosh that the user not only had to remember (or remember where they’d recorded it) but had to, per his ’03 recommendation, change each month into another nonsensical string of random characters and letters.

Burr now regrets these rules and says that he was wrong about them.

Back when he wrote the “rules” on the safest passwords, there simply wasn’t much data, and he says he ran into trouble trying to do his own research because no one wanted to tell him their password.

Times have changed, and despite new data that suggest a four-word phrase is harder to crack than a shorter string of gobbledygook, Burr’s paper was the definitive work on passwords for well over a decade.

The Wall Street Journal reports:

The man who wrote the book on password management has a confession to make: He blew it.

Back in 2003, as a midlevel manager at the National Institute of Standards and Technology, Bill Burr was the author of “NIST Special Publication 800-63. Appendix A.” The 8-page primer advised people to protect their accounts by inventing awkward new words rife with obscure characters, capital letters and numbers—and to change them regularly.

Here’s hoping websites catch on fast. I can’t tell you how many sites I simply avoid because even if I follow their crazy “include a cap, a number, a character, a lower case letter, and a secret keyboard Easter Egg combo . . . in at least eight characters.” I can’t remember what the password is and have to reset it to see one thing or make one comment.

The document became a sort of Hammurabi Code of passwords, the go-to guide for federal agencies, universities and large companies looking for a set of password-setting rules to follow.

The problem is the advice ended up largely incorrect, Mr. Burr says. Change your password every 90 days? Most people make minor changes that are easy to guess, he laments. Changing Pa55word!1 to Pa55word!2 doesn’t keep the hackers at bay.

Also off the mark: demanding a letter, number, uppercase letter and special character such as an exclamation point or question mark—a finger-twisting requirement.

“Much of what I did I now regret,” said Mr. Burr, 72 years old, who is now retired.

There is no site (that isn’t paying me) that I need to see so badly that I will jump through the hoops of proving who I am and then resetting a new password that I will also never remember (and will need to reset next time . . . not that there would be a next time).

While my experience is anecdotal, there has reportedly been a measurable decline in user engagement and usage due to onerous, and ultimately, it turns out, ineffective and needlessly extravagant password requirements.

The Wall Street Journal continues:

The new guidelines, which are already filtering through to the wider world, drop the password-expiration advice and the requirement for special characters, Mr. Grassi said. Those rules did little for security—they “actually had a negative impact on usability,” he said.

Long, easy-to-remember phrases now get the nod over crazy characters, and users should be forced to change passwords only if there is a sign they may have been stolen, says NIST, the federal agency that helps set industrial standards in the U.S.

Amy LaMere had long suspected she was wasting her time with the hour a month it takes to keep track of the hundreds of passwords she has to juggle for her job as a client-resources manager with a trade-show-display company in Minneapolis. “The rules make it harder for you to remember what your password is,” she said. “Then you have to reset it and it just makes it take longer.”

When informed that password advice is changing, however, she wasn’t outraged. Instead, she said it just made her feel better. “I’m right,” she said of the previous rules. “It just doesn’t make sense.”

Four random words in some random order is now deemed more secure than the “one of everything” string.

The Wall Street Journal continues:

Academics who have studied passwords say using a series of four words can be harder for hackers to crack than a shorter hodgepodge of strange characters—since having a large number of letters makes things harder than a smaller number of letters, characters and numbers.

In a widely circulated piece, cartoonist Randall Munroe calculated it would take 550 years to crack the password “correct horse battery staple,” all written as one word. The password Tr0ub4dor&3—a typical example of a password using Mr. Burr’s old rules—could be cracked in three days, according to Mr. Munroe’s calculations, which have been verified by computer-security specialists.

How hard is “eggscategorydoorheir” and not changing it every month? Not hard for me, but apparently hard for hackers.

That’s a win/lose I can live with.

Donations tax deductible

to the full extent allowed by law.

Comments

Using words as passwords is terrible advice, I’m not sure if WSJ thought about this. Dictionary attacks are a thing. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dictionary_attack

The key to a pass phrase is the inclusion of the space character. The time it takes a computer using a dictionary attack to break a pass phrase of four random words operated by spaces is greatly increased. I’ve been an advocate for the use of pass phrases instead of Burr’s string password for years, and they’re far better for user retention and security alike. The problem is most security libraries online do not permit spaces in a password and limit the number of characters a person can use which makes pass phrases impossible.

They understand dictionary attacks. You should actually read the science behind it.

Basically if you look at all the words in english, 171,476 in common use according to Google, but then you can add English names and locations to really push that number up. Pick any 4 and you have (171476)^4 password options to test. 8×10^20 combinations (Before including people or place names).

If you have an 8 character alphanumeric password you have around 100 options per character, which gives you 100^8 or 10^16 combinations. or about 80,000 times less combinations than the four word option. And it’s even worse because you are forced to have a number (only 10 options) and an alphanumeric character (20ish options) and Mixed Capitals, so a lot of those 10^16 combinations are invalid and don’t need to be tested.

Dictionary attacks work well against alphanumeric passwords because people like to pick passwords that look like words, that reduces your viable passwords even further. With the 4 word solution your having the dictionary doesn’t actually reduce the password space from almost 10^21, you have to test all of them.

A dictionary attack is a form of “brute force” attack that is really more applicable to encryption cracking than hacking online software accounts. Your typical online (web based) software system is going to have multi-layered security that will detect and stop a dictionary attack fairly quickly because it would result in thousands (or millions) of repeated and failed authentication attempts. Intrusion detection systems will detect this and shut it down long before the correct password is found.

Cool.

From now on my password will be onlyloserschangetheirpassword. 😀

nowayimachangemine

If you keep the word order random, sure. It it’s something meaningful, then the randomness is lost, and cracking is easier. “Now is the winter” is much easier to crack than “winter now the is”, but which of the two is a user likely to remember, and therefore use?

Banks and credit card companies.

Yes, and they are usually the ones with the worst password policies.

Banks and Credit Card Companies are regulated under the PCI (Payment Card Industry) standard as are merchants and retailers who use payment card information. While PCI standard isn’t necessarily a set of laws, it might as well be, as to not conform to the current guidance is to fail audits, is to lose business. Do contracts with Fortune 500 companies also often include specific passwords security requirements? You betcha. Do I think that institutional change in this area will be quick? Nope.

Four-word passwords are great — if you’re the only one doing it.

Once everyone is using four-word passwords, the hackers will know that and the algorithms to crack them become much, much simpler and faster.

Here is a decent attempt at explaining the difficulty of “guessing” a random worded pass phrase: https://xkcd.com/936/

“Modern password crackers combine different words from their dictionaries:

What was remarkable about all three cracking sessions were the types of plains that got revealed. They included passcodes such as “k1araj0hns0n,” “Sh1a-labe0uf,” “Apr!l221973,” “Qbesancon321,” “DG091101%,” “@Yourmom69,” “ilovetofunot,” “windermere2313,” “tmdmmj17,” and “BandGeek2014.” Also included in the list: “all of the lights” (yes, spaces are allowed on many sites), “i hate hackers,” “allineedislove,” “ilovemySister31,” “iloveyousomuch,” “Philippians4:13,” “Philippians4:6-7,” and “qeadzcwrsfxv1331.” “gonefishing1125” was another password Steube saw appear on his computer screen. Seconds after it was cracked, he noted, “You won’t ever find it using brute force.”

This is why the oft-cited XKCD scheme for generating passwords — string together individual words like “correcthorsebatterystaple” — is no longer good advice. The password crackers are on to this trick.”

=========================

Even better is to use random unmemorable alphanumeric passwords (with symbols, if the site will allow them), and a password manager like Password Safe to create and store them. Password Safe includes a random password generation function. Tell it how many characters you want — twelve is my default — and it’ll give you passwords like y.)v_|.7)7Bl, B3h4_[%}kgv), and QG6,FN4nFAm_. The program supports cut and paste, so you’re not actually typing those characters very much. I’m recommending Password Safe for Windows because I wrote the first version, know the person currently in charge of the code, and trust its security. There are ports of Password Safe to other OSs, but I had nothing to do with those. There are also other password managers out there, if you want to shop around.

There’s more to passwords than simply choosing a good one:

Never reuse a password you care about. Even if you choose a secure password, the site it’s for could leak it because of its own incompetence. You don’t want someone who gets your password for one application or site to be able to use it for another.

Don’t bother updating your password regularly. Sites that require 90-day — or whatever — password upgrades do more harm than good. Unless you think your password might be compromised, don’t change it.

Beware the “secret question.” You don’t want a backup system for when you forget your password to be easier to break than your password. Really, it’s smart to use a password manager. Or to write your passwords down on a piece of paper and secure that piece of paper.

One more piece of advice: if a site offers two-factor authentication, seriously consider using it. It’s almost certainly a security improvement.

The full article is at https://www.schneier.com/blog/archives/2014/03/choosing_secure_1.html

I ran all the password examples given in the article through Gibson Research Corporations haystack calculator. I’d suggest everyone do so just for fun. The results are amazing and nothing like Randall Munroe suggested. There is also a password generator on the site that will give you what is essentially an unbreakable password.

https://www.grc.com/haystack.htm

I gave it a go with an old password. It is of the string of gobble type and 16 characters in length. ($29.95 + SH I’ll share) Part of the results include:

O/L Attack Scenario: (Assuming 1,000 guesses per second) 14.14 million trillion centuries

Offline Fast Attack: (Assume 100 billion guesses per sec) 1.41 hundred billion centuries

Massive Cracking Array: (Assume 100 trillion guesses per sec) 1.41 hundred million centuries.

I note that the site indicates that it is not a “strength indicator,” yet the password seems rather strong to me.

In real life, most financial sites and a lot of other sites will lock you out after three wrong guesses. Apple phones have a four digit PIN number, but after a couple of wrong guesses, make you wait before retrying. The wait time expands exponentially.

I don’t believe any ordinary person will ever be hacked by password guessing. The greatest vulnerability is having one’s passwords stolen en masse by someone who hacks a store or bank.

Exactly. Give me the password heap and I’ll probably find out at least 10% of them in a couple of minutes. Used to run audits when I was the CTO

But then again, some people let their browser “remember” their account ID and password. Sucking that info down is relatively simple and you get all the keys!

Really? How do you do that?

I have changed my pass word from “12345” to “1234567890”. I feel much safer. : >

In general, length of password matters most, so a passphrase such as “I like this here website a whole lot!” is fairly safe.

I tend to use 20+ for some sites and for sites where I can, I use 33+ character passphrases.

Sadly, one of my banking institutions has a fairly weak policy…8 characters, upper/lower/cuss case required. And they make you change it every four months. Oh…and your last 12 passwords are “no go” words.

Of course, “Password!234” becomes “!234Password” and passes their “rigorous” standards. (sigh)

Which is simple if you are using passphrases, since you start the sentence somewhere else.

Two factor authentication isn’t bad…until you lose your cell phone where they send the SMS to so that you can “confirm” yourself. Hence a good reason to have a Google Voice/MagicJack number that isn’t attached. But then…yeah…problems with “network” captured data or leakage at GV/MJ.

You can only avoid being “low hanging fruit”, even though you still will be on the same tree being plucked.

/End Ramble

One of the best cyber-security mechanisms in widespread use today is “multi factor authentication.” This means that logging in to a system requires both something you know and something you have.

Originally this meant you needed to enter your password plus a random number generated by a little “key fob” you would be issued typically by your corporate IT department. These key fobs were a major hassle and they’re being phased out by apps you can put on your smart phone. Many banking and brokerage web sites, and even email hosts like gmail, offer this option now.

4 words? mypasswordispassword

Remember, randomness counts. (grin)

I’ve been saying this for over a decade that forcing you to change your password every couple months is the stupidest and most counter-productive thing ever.

Especially for any system people don’t use multiple times a day, if they have to change the password every 30, 60 or 90 days, what do they do? They can’t remember the password they changed to, so they WRITE IT DOWN.

I recall reading a security study of a system that required people to change the password every 30 days and had something like a 12 character requirement with typical characters (1 upper 1 lower 1 number 1 non-alpha numeric).

What was the result? 80% of users had their current password physically written down within 3 feet of the system it accessed.

This holds true regardless of location. If you’re in an office with password login requirements – go desk to desk and look at the back side of keyboards. You will truly be shocked at how many passwords you find.

Forcing people to change passwords on short intervals has not, and never will, increase security.

Most government systems require 16 digits to include 2 uppercase, 2 lowercase, 2 numbers and 2 symbols. That pretty much leaves you going up and down a keyboard row while alternating your use of the shift button. I’d say 40% of government employees have the exact same password. Then you have John Podesta who used “passw0rd”…

Why do the sites require passwords? Do I really care if someone guesses my password for Legal Insurrection and assumes my identity?

I really only care about passwords on sites that someone can buy something in my name or transfer funds. For all the others, any hacker can try “Password” plus my mother’s maiden name and my daughter’s birthdate and have a ball posting lots of obnoxious posts in my name!

Many years ago—back when the Internet was powered by steam, as I recall—my bank announced a brandy-new online presence … but it only worked properly through Internet Explorer.

Since Explorer was at that time Microsoft’s gift to hackers, I moved to another bank. Voilà, security vulnerability problem solved.

What if 65 million people have Hillaryforprison2017.

https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-secret-to-remembering-passwords-ask-a-magician-1501689355

That’s one strong, perfect password. And who would suspect I’d really use it, now that I’ve published it in The Wall Street Journal?

But hold on. I’ve overlooked the most basic principle of magic.

I’ve just flipped through “The Encyclopedia of Card Tricks” and plunked my finger down 15 times at random. Each time, I noted whatever character, numeral or mark of punctuation I happened to land on. I have, in other words, created a 15-character password that’s totally random. It’s not the name of my dog, my favorite band or the street I grew up on. No one who knows me, however intimately, could guess it.

And I’ve written the utterly random password down. Yes, I’ve written it down—just as I advised you not to. But I’m not telling you where. It’s somewhere in my office, somewhere easy to see from my computer. It might be broken up into different parts. Some of it might be big. Some might be very small. But only I know where to look.

And now I’m tacking a bright pink sticky note onto my computer monitor screen. On it—in very thick, black marker—I’ve written PW-FOO7BA1176#. I believe with a strong pair of binoculars you could read that from the park outside my window.

The technical term for this pink note is “misdirection.”

And that—as any magician will tell you—is the strongest security you can have.

Back before you could choose your own PIN for ATM cards, I used to do this. I’d encrypt my PIN using an algorithm I thought up, that I guarantee nobody else would ever think of in a million years, and write the result, which was another four-digit number, on the card in plain sight, exactly as they warn you not to.

Every time I wanted to use one of my cards I’d decrypt it, but my hope was that a thief would just try that number, when it was rejected he’d think he mistyped it and try again, and the third time he’d try some simple transform such as reversing it, and then the machine would eat the card and notify me. I never lost any of my cards, so I never got a chance to find out whether my idea worked. And now that you can choose your own PIN I pick the same one for all my cards, so I don’t need to encrypt it. I guess I should still write a random number on them, but I got out of the habit.

ohs#!tiforgot