The internet didn’t break today, but there’s always tomorrow

Today’s internet problems could be a bad omen.

I noticed the problem accessing Twitter.

Tweets not loading fully, the site timing out. That wouldn’t be the first time Twitter has had a hiccup, but it lasted a long time.

Here’s why, via Gizmodo, Today’s Brutal DDoS Attack Is the Beginning of a Bleak Future:

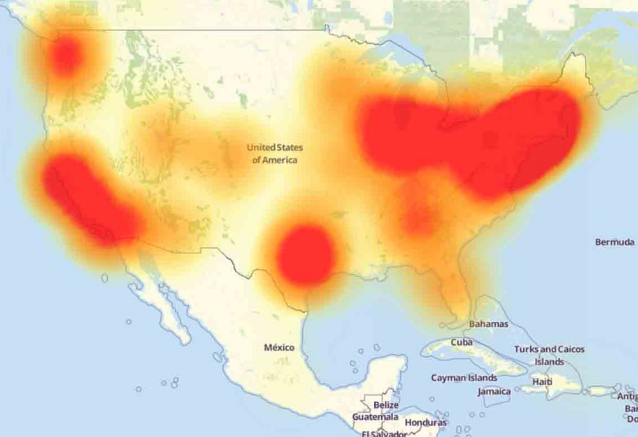

This morning a ton of websites and services, including Spotify and Twitter, were unreachable because of a distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack on Dyn, a major DNS provider. Details of how the attack happened remain vague, but one thing seems certain. Our internet is frightfully fragile in the face of increasingly sophisticated hacks.

Some think the attack was a political conspiracy, like an attempt to take down the internet so that people wouldn’t be able to read the leaked Clinton emails on Wikileaks. Others think it’s the usual Russian assault. No matter who did it, we should expect incidents like this to get worse in the future. While DDoS attacks used to be a pretty weak threat, we’re entering a new era….

Recently, we’ve entered into a new DDoS paradigm. As security blogger Brian Krebs notes, the newfound ability to highjack insecure internet of things devices and turn them into a massive DDoS army has contributed to an uptick in the size and scale of recent DDoS attacks. (We’re not sure if an IoT botnet was what took down Dyn this morning, but it would be a pretty good guess.)

Gizmodo points a prior post — which we linked in the Post of the Day previously — by Bruce Schneier, Someone Is Learning How to Take Down the Internet:

Over the past year or two, someone has been probing the defenses of the companies that run critical pieces of the Internet. These probes take the form of precisely calibrated attacks designed to determine exactly how well these companies can defend themselves, and what would be required to take them down. We don’t know who is doing this, but it feels like a large nation state. China or Russia would be my first guesses….

Recently, some of the major companies that provide the basic infrastructure that makes the Internet work have seen an increase in DDoS attacks against them. Moreover, they have seen a certain profile of attacks. These attacks are significantly larger than the ones they’re used to seeing. They last longer. They’re more sophisticated. And they look like probing. One week, the attack would start at a particular level of attack and slowly ramp up before stopping. The next week, it would start at that higher point and continue. And so on, along those lines, as if the attacker were looking for the exact point of failure.

The attacks are also configured in such a way as to see what the company’s total defenses are. There are many different ways to launch a DDoS attack. The more attack vectors you employ simultaneously, the more different defenses the defender has to counter with. These companies are seeing more attacks using three or four different vectors. This means that the companies have to use everything they’ve got to defend themselves. They can’t hold anything back. They’re forced to demonstrate their defense capabilities for the attacker.

Taking down the electric grid used to be our big worry. And it still is.

But taking down the internet would be just as paralyzing. The only thing preventing huge devastating cyber attacks by the major state actors is the same old concept of mutually assured destruction.

But what if a state actor isn’t involved. Wikileaks sent out this curious tweet:

Mr. Assange is still alive and WikiLeaks is still publishing. We ask supporters to stop taking down the US internet. You proved your point. pic.twitter.com/XVch196xyL

— WikiLeaks (@wikileaks) October 21, 2016

Donations tax deductible

to the full extent allowed by law.

Comments

…..and Obama (and a lax, hideous Congress, led by spiteful, RINO McConnell), GAVE AWAY CONTROL OF THE INTERNET…..

Only Ted Cruz was the lone reed, the voice crying into the wilderness – DON’T LET THIS HAPPEN.

Now, we have literally nothing we can do. We are at the mercy of ICANN.

Having a problem accessing Twitter is not necessarily a bad thing.

A smudge on the x-ray of your right lung is a bad thing. Accessing Twitter not so much.

I hope you’re not talking about yourself there.

A very naive remark, considering that the x-ray machine is connected the same way that Twitter is.

And that the x-ray machine probably has a thousand vulnerabilities that allow a determined person to go in and put a virtual spot on your x-ray or delete one.

What do you think “IoT” means?

What color is the sky on your planet? How many suns?

Anchovy: Thank you for that thought.

An interesting comment on the attack:

http://arstechnica.com/security/2016/10/double-dip-internet-of-things-botnet-attack-felt-across-the-internet/?comments=1&post=32109655#comment-32109655

Global warming caused this, in cahoots with George W. Bush.

Is that you Obummer?

No, Henry, let’s put the blame where it belongs: Algore is to blame for doing such a piss poor job of creating the internet!

Wasn’t me, I went to Williams Gun Sight today. Just browsing.

Wikileaks also said there were heavily armed police around the embassy tonight and included a picture.

You can find solid reporting from Brian Krebs (krebsconsecurity.com) – his site was the target of a similar attack, which caused his host to determine that it was too expensive to continue hosting the site. That came after reporting on a group selling attack services. The malware has been published, which means that this attack and any follow ons could come from anywhere.

My guess is that it was perpetrated by xenophobic, transphobic, troglodytephobic, misogynistic, arachnophobic individuals whose toxic masculinity is affecting climate change which in turn overloads the internet with greenhouse gasses emitted from Al Gores ass.

Or… it just may be that Bill Clinton’s love child is pissed

There’s something very fishy about all this; it’s not what it seems.

Our internet is frightfully fragile in the face of increasingly sophisticated hacks.

Actually, it’s not. Its original purpose, back when it was DARPAnet, was to be a communication system linking government, military, major defense contractors, and schools which do major defense research, and it was intended to be able to function even during and after a major nuclear attack. And that’s why the architecture is distributed, and massively redundant. Single-point attacks should be water off the digital duck’s back. Much of the Net could be physically destroyed, but the rest would function unimpaired; unlike, say, the telephone network, there are no central switching centers, in fact no central anything. The DNS system—the addressing scheme which lets computers find other computers on command—is a pile of redundancies. This is why when you change something like the DNS computer for your own web sites (because you’re changing web hosts, or because your web host is moving all the sites to a new computer, or even a new data center), and you then try to check that you did everything right by typing your web site name into a browser’s address bar, you most likely won’t find your site at the new address (the one in xxxx.xxxx.xxxx.xxxx format), but still at its old address. But a few hours later, you try again, and it’s at the new address. The DNS information—the thing that translates the address you can use, like “legal insurrection”, to the number format computers can use, takes hours to diffuse around the world to the various DNS root name servers. These are supposed to be scattered around the planet, for safety against physical attack or natural disasters, but in practice most are in the US. But your computer doesn’t need the root name servers to find an address; it asks other computers on the network. That’s also information which takes a while to propagate, but if you haven’t changed your site address recently, there should be no problem if computers try to find it at an old address.

In short, this doesn’t look to me like a Denial of Service attack. DoS attacks work fine against a particular site (even a big one, like Yahoo or eBay). But they shouldn’t do anything much when the targets are the name servers at Dyn or Tucows or any of those outfits, because even if those operations are successfully paralyzed, the redundancies should make that unnoticeable to users.

Somebody is looking to shut off the Internet some other way … what that is, I can only speculate.

Recall Obama’s reported interest in an Internet “kill” switch. There have been a few Executive Orders along related lines, as well as some Congressional activity, but exactly how a distributed system could be simply turned off remains murky. There’s no big switch in a vault somewhere which would turn the whole thing off, or a plug someone can pull; even if such a thing existed, the entire system is designed to automatically find a way around any such hardware. In principle Obama could tell America’s 8,000-plus ISPs (Internet Service Providers, the outfits whose bill you pay every month) to just turn off; that wouldn’t affect the Internet itself, but it would prevent most of us from connecting to it, which is just as good. But by what authority he could compel compliance is another mystery.

You’re right 99%.

One thing I find interesting is the insistence in blaming Russia for every little thing that happens online.

Yes, it COULD be Russia. Or not.

It takes either blissful ignorance or malicious intent to pinpoint a botnet attack on someone so quickly. IF it was indeed what they say it was.

Now, about that 1%:

DNS configuration updates used to take hours to propagate. I remember there was a time when you sometimes had to wait a full 48 hours.

That’s not the case anymore.

Nowadays, DNS updates propagate fairly quickly. Usually less than a minute, if you use any major provider. Some people sometimes end up waiting for hours, but that’s only because their local network is not properly configured, or because they forget, or do not know how to flush their own DNS cache. As simple as that.

One thing I find interesting is the insistence in blaming Russia for every little thing that happens online.

Still waiting for some evidence on that. All they’ve presented so far wouldn’t fool anybody except the terminally clueless.

Nowadays, DNS updates propagate fairly quickly.

Propagation time isn’t the issue. It should be of interest to readers of a non-technical site since it’s one of the phenomena which would clue an alert user into one of the ways by which the whole system works. But the salient point is that the information which makes the addressing system work propagates automatically to redundant points worldwide, and you can observe it doing so yourself—no need to take anyone’s word for it. And, once propagated, no DoS attack can affect it.

So, whatever happened here, it wasn’t a DoS attack.

The news articles seem to assume that it was, perhaps because that’s the only type of attack they know about. That’s like opining, sagely and ponderously, that all illnesses are caused by “some bug going around”.

It was ARPANET, with research funding coming from DARPA.

You are correct about the redundant nature of the architecture, and yes it was designed that way so that the overall network could withstand large parts of it being disabled, perhaps in a nuclear war.

However, the internet today is commercialized beyond the wildest dreams of the original designers. There are now many trunk lines that carry massive volumes of traffic which, if disabled, could cripple large portions of the network. Other bottlenecks to large commercial traffic flows exist.

In short, there are many points of vulnerability which would not disable the entire network but which would render it useless for huge numbers of people.

Consider how important this network is to commerce today. This isn’t just twatter. Virtually every company in the US is dependent upon the network to varying degrees. Logistics for many just in time supply chains depend upon it. Disabling even parts of it could cost people their lives. So this is tantamount to an act of war, and we should react accordingly.

It was ARPANET, with research funding coming from DARPA.

That’s revisionism. In the very early days nobody pretended that it wasn’t a part of the US defense system, and it was DARPAnet. There was no commercial activity back then. Later, when The Decision was made to go commercial, and the famous COM TLD appeared, the D in DARPAnet was dropped, perhaps because some worrywart thought the martial allusion would scare off some customers. Nobody ever said anything about it, at least that I saw, but in print everybody (except me, of course) gradually stopped calling it DARPAnet in favor of ARPAnet. Seemed pretty silly to me; but of course a lot of things do. It gets even sillier; the agency itself seems to change its preference every now and then. When it was funding my research in grad school it was DARPA, and so far as I’m concerned DARPA it will stay.

There are parts of the Internet which were added in the cheapest possible way. For a while all of Europe was connected through a single phone line (a big one, true, but still just one) with a terminus under a parking lot in New Jersey. Not a lot of redundancy there. But nobody really bothered about it, because it was a US defense system, and that part remained protected by multiple redundancies. Whether or not the countries hitching cheap rides were also so protected, well, that’s their problem. So why did Europe go the slap-dash route? It was cheaper. That’s all. Maybe if you’re not concerned with defense against nuclear attack you can afford to be cheap.

Even now, parts of the world which are out at the ass-end of nowhere, and connected to everyone else by a small number of lines, can of course turn those lines off by government fiat. But to think that’s how the important part of the net works is to misunderstand its architecture completely.

Consider how important this network is to commerce today.

Nobody’s claiming that it’s not important. I’m claiming that if the articles we’ve been seeing about the attack are really all they know about it, then they have no clue about what the real problem is.

I started college in 1986 and was immediately in love with it via the VAX VMS platform our CIS program ran. It sounds like you’re a bit older than me. As you say, everythjng I’ve been taught and have read in the trade press, which is a shit-ton, always calls it ARPANET. But if you’re saying it was originally called DARPANET then ok. A citation would be nice to see.

My comment about the criticality of it wasn’t aimed at you, but at other comments along the lines of ‘who cares if Twitter is down’

After looking into this some more, I see that the agency itself was originally named ARPA and didn’t change it’s name to DARPA until 1971, well after the project was underway.

Just a note- the most of a day outage of a major cell phone carrier, along with the complete outage of cellphone service for an hour or so in DC has disappeared down the memory hole. happened back in June. No public explanation was ever given.

Bruce Schneier wrote an article about this. Might be an interesting read for some https://www.lawfareblog.com/someone-learning-how-take-down-internet

In the “olden” days, every organization would have its own caching DNS server which would store domain name and IP address information for the whole organization. Since this information was cached for up to three days, most people would never even notice outages of a few hours. Google runs a public DNS server which seems to work really well and some ISPs have good setups. Nowadays most people just take 100% available DNS servers for granted, but if you or your ISP had the right setup today then you still should have had no problem visiting all of your favorite sites,

And by the way, the whole “Internet was designed to survive a nuclear war” thing is just a myth. When the Internet was starting out, the biggest component was NSFnet which was a non-commercial network with mainly universities. Leased lines were not that stable or reliable back then, but they were relatively cheap, so the network planners made sure that each metro area was connected to 2-3 others.

http://www.wired.co.uk/article/h-bomb-and-the-internet