RIP American Marine Lou Lenart: Israel’s 1948 War Hero

“The Man Who Saved Tel Aviv” Dies at 94

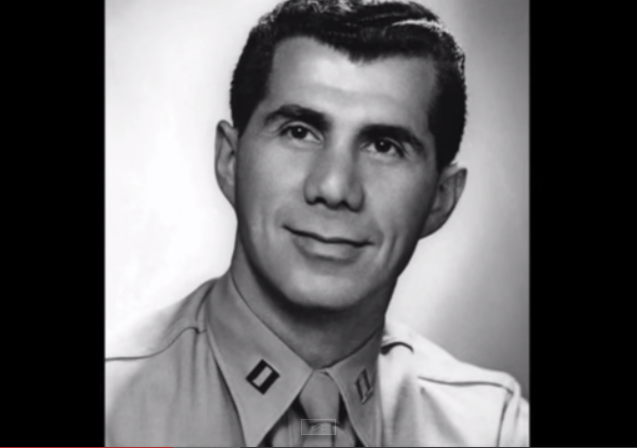

Louis (Lou) Lenart, an American fighter pilot during World War II who later helped to fend off an Egyptian advance on Tel Aviv during Israel’s 1948 War of Independence passed away on Monday (July 20) at his home in the central Israeli city of Ra’anana.

Lenart is a legend in Israel, where he’s hailed as “The Man who Saved Tel Aviv”.

On May 29, 1948—just two weeks after the fledgling Jewish state was invaded by the armies of five Arab nations—Lenart led the newly-formed Israel Air Force’s (IAF) first combat mission, stopping a massive Egyptian army column less than 30 miles away from Tel Aviv.

In what can only be described as one of the greatest fake-outs in military history, Lenart—who, as the most experienced pilot, led the assault—and his three buddies flew four junk Czech-built German Messerschmitt fighter planes for a country that had no actual airforce. Dropping 70 kilogram bombs on the Egyptian column and attacking them with gunfire, this bit of daring-do managed to convince the Egyptians that there was enough competition in the sky to warrant a retreat.

There can be no doubt that Lenart helped to turn the tide of the war.

Had the Egyptians been able to advance to Latrun they would’ve joined the Jordanian troops. Lenart’s mission pushed back a crucial enemy advance, helping to save the new Jewish state from what would’ve been a near certain defeat during that phase of the war.

As reported in several obituaries, one of Lenart’s future business partners commented that:

In many ways Lou was what Lafayette and Nathan Hale were to the American Revolution. If it hadn’t been for Lou and his three comrades, Tel Avivians would be speaking Arabic today”.

According to The Times of Israel, Lenart later told an Israeli Air Force magazine that “It was the most important event in my life. I survived World War II so I could lead this mission”.

In a previous LI post, I describe this and other feats of high-flying chutzpah during the second phase of the 1948 war, when the Arab states aimed to overrun and cripple the Jewish state and “throw the Jews into the sea”.

These heroic exploits were accomplished by no more than a handful of quickly trained young Israeli pilots, including Ezer Weizman—who would go on to become Israel’s President—and a gutsy team of volunteer Jewish American World War II vets who gave up their comfortable post-war lives in America to answer Israel’s call for help.

Their little-known true stories and the 1948 beginnings of the scrappy Israeli Air Force have now inspired three films—two feature-length documentaries and a major motion picture.

Lou Lenart: American Marine, Savior of Tel Aviv

Lenart was born in 1921 in a small Hungarian village near the Czech border.

To escape anti-Semitism, his family moved to America when he was 10 years old and settled in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania.

As described in a Jewish Journal obituary, Lenart grew up experiencing the anti-Semitism of 1930s America, when “the kid with the funny accent again was the target of anti-Jewish taunts”.

Lenart enlisted in the Marine Corps at 17 and talked his way into flight school, where he nearly died after a midair collision during training. He saw action during the Battle of Okinawa and elsewhere in the Pacific theater.

Discharged after the war with the rank of captain, he learned that 14 of his Hungarian relatives had been murdered in Auschwitz.

As I discuss in my previous LI post, Lenart joined Al Schwimmer, who worked for TWA and had been a flight engineer for the U.S. Transport Command in World War II, in a clandestine effort to smuggle surplus planes into the fledgling state of Israel in early 1948.

Following the 1948 war, Lenart participated in Operation Ezra and Nehemiah which brought Iraqi Jews to Israel, and worked as a pilot for the El Al airline. Subsequently, he became a Hollywood producer. In recent years, he divided his time living in Los Angeles and Israel and became a Hollywood producer.

According to YNet, a restaurant near LAX airport has put a Messerschmitt plane on display in his honor.

Lenart was 94 when he died of heart and kidney failures. He is survived by his wife, Rachel Nir, daughter Michal Lenart—who also joined the Israel Air Force—and a six year old grandson.

He will be laid to rest on Wednesday (July 22) at the Kfar Nachman Cemetery in Ra’anana. Expected to attend the funeral are high-ranking officers of the U.S. Marine Corps and Israel Air Force.

Lou Lenart is a true American and Israeli hero.

May his memory be for a blessing.

Miriam F. Elman is an associate professor of political science at the Maxwell School of Citizenship & Public Affairs, Syracuse University

Donations tax deductible

to the full extent allowed by law.

Comments

Semper Fidelis Captain Lenart. What a life, what a story!

God bless him and may his memory last forever. Every year I celebrate the Nakba, Hiroshima and Nagasaki. My dad, a commander of a crack antiaircraft unit, was scheduled to be on the second wave on the first landing in Japan to shoot down the kamikaze fighters headed over the beach to destroy the troop ships. Every year from the time I was 18 until he died we celebrated with a 12 pack. Our enemies: kill them all by whatever means possible.

That’s an ME-109 with the Star of David on it. Hitler’s ashes must have been spinning around in miniature dust devils.

The ME-109 was a good airplane. The irony of it all has always struck me.

Semper Fi, Louis Lenart. Rest your oar, shipmate.

If anyone takes offense at me, a sailor, calling him shipmate, well…

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/35/5-inch_38-caliber_cropped.jpg

Note the Globe and Anchor. Traditionally Marines operated secondary gun mounts on US capital ships about when Louis Lenart served.

Fair winds and following seas.

The 109 was an antique by then. A brilliant design for the 1930s, but nearly a decade of development resulted in a heavy ship with very high landing and takeoff speeds. The nasty narrow ’30s undercarriage combined with high speeds tended to kill novice pilots. Well, the Nazis never liked Prof. Messerschmitt much anyway.

It’s hard to tell for sure, but the one in the photo looks like an Avia S-199. That was a Bf-109G with the wrong engine/prop in it; a Junkers Jumo in place of the proper Daimler-Benz unit. The change messed up the guns; and, even worse, the thing flew like a pig. Capt. Lenart was obviously a courageous man.

The Alex Yofe book ‘Avia S-199 in Israel Air Force Service’ states that it was indeed the Avia S-199 that Lenart flew. Often called the ‘mule’ by Czech pilots who had the misfortune to fly it. Several were lost in take-off or landing accidents.

My opinion of the ME-109/Bf-109 (Bayerische Flugzeugwerke) is primarily if not exclusively influenced by Eric “Winkle” Brown, Royal Navy. He is perhaps most famous as a test pilot at the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE), Farnborough, during WWII. He has flown more basic aircraft types than anyone in history, 487, and is the RN’s most decorated living officer (happily he is still with us at 96).

All I know is he didn’t consider the ME-109 to be an antique in 1944. The USAAF was experiencing unacceptably high escort losses. Planes would dive to intercept German fighters and would crash because they weren’t able to recover.

At the time the RAE was the world leader in testing high speed and transonic flight conditions. So General Doolittle, 8th Air Force, turned to them for help. Brown tested all the primary escort fighters; P-47, P-38, and P-51, against captured ME-109s and FW-190s.

He found that a certain mach number all the planes would experience such high stick forces that recovery would become impossible, but that mach number was higher for both German fighters than any American fighter than the P-51. The P-51 had the edge over all the fighters in that regard. Brown’s tests provided Doolittle with the ammo he needed to argue exclusively for P-51s in the European theater as bomber escorts.

The ME-109 commanded respect throughout WWII, from beginning to end, from both the pilots who flew them and the pilots who flew against them. I don’t recall in detail what Brown had to say about the aircraft, but I recall that he had a high opinion of the ME-109G he flew in 1944.

“The Bf-109 always brought to my mind the adjective ’sinister.’ It has been suggested that it evinced the characteristics of the nation that conceived it, and to me it always looked lethal from any angle, on the ground or in the air; once I had climbed into its claustrophobic cockpit, it felt lethal!”

Brown said the ME-109G was “delightful to fly and “performed efficiently both in dogfighting and as an attacker of bomber formations” but he qualified his opinion saying, “providing the Gustav was kept where it was meant to be.” That is, at high altitude.

To wring out the maximum performance the aircraft industry of 1934 could put into an airplane, Willy Messerschmitt left out what designers sometimes call “stretch”. He took the best engine he knew he could get, a Daimler Benz—not the best available to him, which at the time was a BMW, but the best which would be available in large quantities in the event of a major war— and designed the airframe around it. He minimized frontal area (and therefore drag) by wrapping the sheet metal of the nose tightly around the engine, giving the 109 that angular, boxy shape so obviously different from, say, the graceful Hawker or Curtis aircraft of the period. The wing airfoil section was unusually thin, again in the interests of low drag. The clipped wing tips were a brilliant way of minimizing the basically intractable problem of tip vortices, again something other talented designers tried to solve by fudge and compromise (probably most famously by Reg Mitchell’s very expensive elliptical planform for the Spitfire wing).

All this made for a very fast airplane, a record-holder when launched (although the Nazis, characteristically, lied it upward to scare their enemies), but made development difficult. As operational altitudes increased and superchargers became bigger and bulkier; they wouldn’t fit inside the 109’s nose sheetmetal, so they had to be hung out the side, which increased drag. The thin wings simply wouldn’t fit wing machine guns, so the 109 made do with two crammed into the cowling in front of the pilot (rather than the six or eight .50s in the wings of comparable British or American aircraft). A more effective alternate was a 20 or 30 mm cannon firing through the propeller gear reduction unit. The cannon fired between the banks of the V-12 engine; the breech was under the pilot’s seat. This would only work with an inverted V-engine, and required the prop centerline to be down low. The low centerline in turn meant that the landing gear had to be relatively tall to keep the prop clear of the ground. The tall landing gear proved difficult to fit into the airframe design; Messerschmitt managed to do it, but the track was relatively narrow. As the craft’s weight increased with development, landing and takeoff speeds did as well, and the narrow undercarriage made it increasingly easy to crash on takeoff or landing. In the hands of an experienced pilot, that was no problem, but novices were far less likely to survive long enough to become that experienced.

The 109 is a particularly interesting case study for machine designers (and not just aircraft designers) because of Messerschmitt’s choices of design tradeoffs. Few machines depend so critically on these choices as fighter aircraft; every feature which is added or enhanced decreases performance in some other respect (usually by adding weight). But optimization makes later development far more difficult. And that’s where a design finally starts to show its age; the more sophisticated the initial design decisions, the more they tend to inhibit later development. I don’t want to say that the later 109 was a triumph of development over design, as that seems to denigrate an unquestionably brilliant design; but dragging its operational lifetime out for over a decade was asking a bit much of an old lady.

(In the photo of Capt. Lenart above, the dark shadow directly to the right of his gun belt is a fairing tacked onto the bottom of the wing, a visual recognition point of the Avias. Like the Germans, the Czechs were unable to cram machine guns into the basic 109 wings, so they slung them underneath and added the fairings…pretty primitive stuff for 1947.)

tom swift said:

“To wring out the maximum performance the aircraft industry of 1934 could put into an airplane, Willy Messerschmitt left out what designers sometimes call ‘stretch'”

Don’t get me wrong; I’m not saying the ME-109/Bf-109 wasn’t past its prime in 1944. I presume by “stretch” you mean room to grow. By that measure the Spitfire was no doubt top dog. Brown considered the Mk. XIV the best fighter of the war. Not bad for a 1930s design roughly contemporary with the ME-109/Bf-109 (once Willy Messerschmidt acquired enough stock and had a controlling interest in the Bayerische Flugzeugwerke the aircraft were called ME rather than Bf, but confusion reigned and still reigns as to what was what).

I am saying that even up until he end of the war the ME-109 remained effective. It might have been marginal, but in the hands of a skilled pilot it could still turn the tables.

I am blatantly appealing to authority at this point, but if Eric Brown didn’t have contempt for it as obsolete in 1944, neither would I.

Which isn’t to say the Israeli Air Force wasn’t provided malengineered garbage by the Czechs.

. . . Lenart joined Al Schwimmer, who worked for TWA and had been a flight engineer for the U.S. Transport Command in World War II, in a clandestine effort to smuggle surplus planes into the fledgling state of Israel in early 1948.

I have heard a lengthy synopsis of this history from a well-informed member of the IDF. THIS is the story that screams out to become a full-length movie!

Great story. Thanks.

Lou, indeed was a hero of two countries, USA and Israel. But Lou was a humble man, Any time one told him he is a hero, he would dismiss it saying ” I am not a hero, I am just lucky. While flying up high in the sky [and even flew a supersonic jet at 60 years old] defending freedom and democracy, he was down to earth. Lou was one of my mentors. We will miss him dearly. Rest in peace Lou!

Indeed a war “Hero,” no need to quibble, nothing honorific about it.

His efforts will be all for naught if his daughter and grand son do not produce more survivors.