Can States sink the Iran Nuke Deal? (Update)

Maybe, maybe not, but why not at least try?

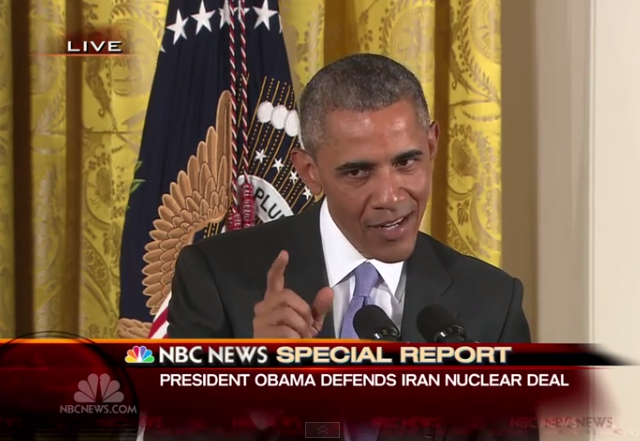

The Obama administration thinks it outsmarted opponents of the Iran deal by running to the U.N. Security Council for international approval before Congress’s review period even started.

It was a typical Obama F-U to his domestic opponents.

Since Congress now needs a super-majority to block the deal, the outcome is uncertain. The Obama team is going all out to pressure Democrats to pledge their loyalty to Obama above all else. Loyalty to Obama is likely to win, though it’s possible Congress will grow some backbone before it comes to a vote.

Obama even is complaining about Israel Lobby money (hint, hint), while John Kerry for the umpteenth time makes implied threats against Israel. Kerry even is on a trip to the Middle East conspicuously not visiting Israel.

Meanwhile, the Ahyatollah and his minions are laughing at Obama, Kerry and the U.S. Not just laughing, mocking and gloating, all the while renewing their vows of death to the U.S. and Israel.

Since the federal goverment appears hapless and hopeless, is there anything the states can do to stop this deal?

Joel Pollak at Breitbart.com was the first, that I’m aware of, to advance a theory of how states can play a crucial role. A reader forwarded the post to me last week while I was in crazyland San Diego, SURPRISE! THE STATES CAN REJECT THE IRAN DEAL:

There is one effective way, however, that the Iran deal can be rejected: states and local governments can refuse to comply with it.

That may come as a surprise. States and local governments do not play much of a role in foreign policy. However, they cannot be forced to implement an international treaty or agreement that is not self-executing–i.e. one whose implementation requires new congressional laws.

Thanks to the victory at the Supreme Court by then-Texas Solicitor General Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX) in Medellín v. Texas (2008), it is a settled principle in constitutional law that states cannot be forced to comply with international treaties unless Congress has passed statutes giving them effect.

Pollak goes on to explain that under the Iran deal the federal government is required to do something it has no power to do, remove state sanctions:

The Iran deal obligates the federal government to take “appropriate steps” to cancel state and local restrictions, and requires the government to refrain from further sanctions in the future. The truth is that the federal government has no constitutional authority to do so.

Divestment laws and contracting restrictions can remain in place at the state and local level until they are superseded by federal statute. The language of the Iran deal itself is not enough to constitute such statutory authority, even if the Iran deal does pass by failure to override Obama’s veto.

If the states want, they can add new sanctions and restrictions on Iran–perhaps to replace those that the federal government is lifting, such as restrictions on Iranian engineers studying nuclear technology at American universities.

The Iran deal specifies that Iran will treat “an imposition of new nuclear-related sanctions, as grounds to cease performing its commitments.” That paragraph (27) deals with federal sanctions, but is written vaguely.

That leaves great power in the states’ hands to trigger the deal’s collapse–or force Obama to re-negotiate.

Will this work?

Two esteemed lawyers, David B. Rivkin and Lee A. Casey, writing in The Wall Street Journal, seem to think this is a possibility, The Lawless Underpinnings of the Iran Nuclear Deal (paywall):

The Iranian nuclear agreement announced on July 14 is unconstitutional, violates international law and features commitments that President Obama could not lawfully make. However, because of the way the deal was pushed through, the states may be able to derail it by enacting their own Iran sanctions legislation….

The Constitution’s division of the treaty-making power between the president and Senate ensured that all major U.S. international undertakings enjoyed broad domestic support. It also enabled the states to make their voices heard through senators when considering treaties—which are constitutionally the “supreme law of the land” and pre-empt state laws.

The Obama administration had help in its end-run around the Constitution. Instead of insisting on compliance with the Senate’s treaty-making prerogatives, Congress enacted the Iran Nuclear Agreement Act of 2015. Known as Corker-Cardin, it surrenders on the constitutional requirement that the president obtain a Senate supermajority to go forward with a major international agreement. Instead, the act effectively requires a veto-proof majority in both houses of Congress to block elements of the Iran deal related to U.S. sanctions relief. The act doesn’t require congressional approval for the agreement as a whole.

The U.N. Charter resolution has trapped the U.S. into a position where it can renounce its obligations only at the cost of being branded an international lawbreaker. The president has thus handed the legal high ground to Tehran and made undoing the deal by his successor much more difficult and costly….

A further legal complication: Even if Congress doesn’t vote to bar President Obama from lifting sanctions on Iran, the president still wouldn’t be able to deliver fully on the deal’s unprecedented sanctions-lifting commitments. They were promised regardless of any future Iranian aggression in the region, sponsorship of terrorist acts or other misconduct.

Some of the U.S. statutes allow the president to lift certain sanctions on Iran. But many of the most important sanctions—including sanctions against Iran’s central bank—cannot be waived unless the president certifies that Iran has stopped its ballistic-missile program, ceased money-laundering and no longer sponsors international terrorism. He certainly can’t do that now, and nothing in the deal forces Iran to take either step. The Security Council’s blessing of the nuclear agreement has no bearing on these U.S. sanctions.

The administration faces another serious problem because the deal requires the removal of state and local Iran-related sanctions. That would have been all right if Mr. Obama had pursued a treaty with Iran, which would have bound the states, but his executive-agreement approach cannot pre-empt the authority of the states.

That leaves the states free to impose their own Iran-related sanctions, as they have done in the past against South Africa and Burma. The Constitution’s Commerce Clause prevents states from imposing sanctions as broadly as Congress can. Yet states can establish sanctions regimes—like banning state-controlled pension funds from investing in companies doing business with Iran—powerful enough to set off a legal clash over American domestic law and the country’s international obligations. The fallout could prompt the deal to unravel….

Law Professor Elizabeth Price Foley writing at Instapundit has a similar take, that state sanctions can be a bother, but it’s unclear how far they can go:

Rivkin and Casey are right about the Constitution’s treaty power being circumvented, with the unfortunate blessing of a cowardly Congress. They’re also right that the Administration’s decision to obtain a speedy U.N. Security Council resolution prior to the Corker-Cardin congressional vote is a blatant and reckless end-run around U.S. sovereignty, bypassing our national legislature in favor of a multi-lateral, extra-sovereign body. Any future President wishing to unravel the Iranian nuclear deal–which Secretary of State has assured us repeatedly is “not legally binding“– will now be branded by the U.N. as an international “law breaker,” a point I made back in April.

I hope States do, indeed, continue to refuse to do business with companies doing business with Iran. The financial impact probably won’t be enough to trigger an Iranian accusation that the Obama Administration isn’t enforcing the deal, however, and consequently the Administration is unlikely to march into court claiming that the Supremacy Clause trumps States’ actions. So I doubt States’ doing this will “prompt the [nuclear] deal to unravel.” Nonetheless, this is one interesting and creative way that States can constitutionally push back.

So where does that leave us?

I’m not sure in practical effect what existing state sanctions would do to interrupt the deal. It is one thing for the states to refuse to comply with obligations purportedly placed on it by a treaty, but it would seem to be something different if the states have laws that actually interfered with the treaty.

I don’t claim any expertise in this area of law, but it seems to me to the extent laws previously have been passed in the States those would continue in effect, but new laws may not be able to be passed.

To really hurt the deal, major states would have to effectively bar a foreign company that does business in Iran from conducting business in the state. For example, if the State of New York barred any financial institution that does business with Iran from doing business in New York, that would have an enormous impact. But I don’t know whether that would create separate legal issues.

In opposing the deal, an all of the above strategy is warranted. By running to the U.N. Security Council before Congress acted, Obama has told the American people that he doesn’t care what we think. And he may get away with it in Congress.

But states have rights. And they should at least attempt to exercise those rights.

UPDATE:

Kerry Admits: States Can Keep Iran Sanctions – Breitbart http://t.co/rzOcchJpXl #IranDeal pic.twitter.com/d6soylpRjV

— Joel Pollak (@joelpollak) July 28, 2015

Donations tax deductible

to the full extent allowed by law.

Comments

“And he may get away with it in Congress.”

Laughing, “May”? With a very few exceptions the entire Republican congress made it perfectly clear he will “get away with it”. By requiring a super majority to block the deal rather than ratify it, the congress made sure they could vote against while upholding it, in order to fool the voters (yes estragon you dope, you).

“It was a typical Obama F-U to his domestic opponents.”

It was a typical Republican F-U to the actual conservatives.

Congress did not “require” a supermajority to block the deal. That was always needed, and there is nothing Congress could have done to change that, without that same supermajority.

The only thing Congress could have done was to permanently remove the president’s power to waive the sanctions; and had there been the numbers to override the inevitable veto, that’s what it would have done. But the numbers weren’t there, so the compromise was to remove this power for only 60 days. That’s not much, but it’s slightly better than nothing. Congress certainly did not make matters any worse.

Mot sure I understand your point. A treaty requires the approval of two-thirds of the Senators present.

Now of course one can always call a treaty is not always a treaty. Why it is a ….

My point is that you seem to imagine there’s something magical about a treaty. In US law a treaty is simply an international agreement for which the president received the consent of 2/3 of the senate. If 2/3 of the senate doesn’t consent then it doesn’t magically go away, it just isn’t a treaty, exactly the same as if the president had not sought the senate’s consent in the first place. So if the president doesn’t want it to have the legal status of a treaty, why would he seek the senate’s consent? What would be the point? He can either achieve the same thing by asking both houses to pass it as a statute, or he can simply let it not be law, and do whatever is in his power to fulfil it anyway.

It is one thing for the states to refuse to comply with obligations purportedly placed on it by a treaty, but it would seem to be something different if the states have laws that actually interfered with the treaty.

Doesn’t the entire rationale for the legality of Obama’s song and dance depend on the claim that his surrender to Iran isn’t actually a treaty?

Yes, exactly; another reason why this post is largely nonsense.

There’s some sense in this post, but also a lot of nonsense. For instance:

Medellin is irrelevant, since this isn’t a treaty. It’s just a private agreement that 0bama has made, which doesn’t bind anyone else. (Legally it doesn’t even bind him.)

Also, even if this were an self-executing treaty and were ratified by the Senate, or if Congress were to pass it as a statute, it couldn’t affect state and local sanctions, since those involve only the states’ or localities’ own money. Congress has no power to tell states and localities how to invest their money.

This is bull***t. The president has never had any obligation to “comply with the Senate’s treaty-making prerogatives”. There is no mention in the constitution of “major international agreements”, and nothing in the constitution requires the president to submit such agreements to the senate. The only purpose of asking the senate to ratify a treaty is to make it the law of the land. There is another, equally valid way for him to achieve that: he can ask both houses to pass it as a statute. But if he doesn’t want it to have the force of law then he needn’t do anything at all.

Corker/Cardin does absolutely nothing to that. Its only effect is to strip the president of the power to waive the Iran sanctions for 60 days, while Congress is considering it. Since the UN sanctions are not going to be lifted until the IAEA reports anyway, this is probably irrelevant. But to the extent that it has any effect at all, it restricts the president’s power rather than expanding it.

More bull***t. Nothing in Security Council Resolution 2231 (2015) prevents member states from imposing or keeping whatever sanctions they like. It merely lifts the requirement that they impose such sanctions. The Iran deal is not law. Only 2231 is law, and it carefully avoids requiring anyone to lift any sanction. If Congress overrides 0bama’s veto and removes his power to waive the sanctions the USA will be in full compliance with the letter of 2231, and that is all that matters. That this would probably cause the whole agreement to collapse is legally neither here nor there. (Morally, of course, it would be a good thing.)

Another point: the “snapback” provision is real. Read paragraphs 11 and 12 of the resolution. On 20-Jan-2017 President Walker could notify the Security Council that the USA believes Iran to be in significant non-compliance with the agreement. It doesn’t even have to be true, though surely it would be. 30 days later, all the UN sanctions automatically come back into force, unless the Security Council votes to stop them; and the USA can veto that.

Of course if the USA were to do this with no evidence, it would make us very unpopular in the diplomatic world, and could hurt us in other negotiations. Also, Russia and China would probably just refuse to reimpose the sanctions, “binding international law” or no “binding international law”; they aren’t in awe of this concept, the way Europeans and some Americans are. And if Russia and China ignore the renewed sanctions the Europeans might follow suit, because their regard for “binding international law” is also more rhetoric than reality; they love to preach it, but they don’t really believe in it.

Also, of course, even if everyone would obey such renewed sanctions, a lot of irreparable damage will be done between now and 19-Feb-2017. For instance, contracts signed before the sanctions come back will be exempt; and you can expect to see a lot of such contracts made in those 30 days.

So the upshot is, if the states want to tie this up in enough years of convoluted legal proceedings designed to scare off any company from investing in Iran, if they ever want to business in the US they are perfectly able to, and the administration’s goofballery in trying to get around running this through as an actual treaty makes it very difficult for them to outright invoke the parts of our legal code designed to prevent that.

Interestingly enough, that sort of thing is exactly why we became a federal system in the first place: unique state by state trade laws made it impossible for outside countries to effectively trade with the US; rather than negotiation treaties with one country, they had to negotiate them with 13 (now 50).

Ironic how the administration’s own lawlessness undermines his own office.

States can’t ban trade with foreign countries. That’s a power reserved for Congress. All they can do is not trade with Iran themselves, and not trade with companies that trade with Iran. That may be enough to motivate companies to decide not to trade with Iran, but it can’t actually compel them.

Thanks for the explanation. In light of the whole BDS thing, I can’t have been the only one wondering how such measures by states “against Iran” could be illegal themselves.

The BDS thing is slightly different. Many states have anti-discrimination laws, which make it illegal to refuse to trade with someone because of his national origin. In those states (and only in those states) one may choose to boycott the State of Israel (or Iran), or specific companies because of something they have done (such as trade with Israel/Iran), but one may not choose not to deal with someone simply because he is an Israeli/Iranian citizen, or with a company simply because it is incorporated in Israel/Iran.

Of course this is often impossible to enforce — the state would have to prove that you would have bought something but for the vendor’s national origin — but if you are a corporation with a formal policy of boycotting all Israelis or Iranians, even if they’ve done nothing that you disapprove of, then the existence of the policy is proof of illegal discrimination.

Note, however, that these are state laws, and therefore don’t bind the state itself unless it wants to be bound. If the state legislature passes a law requiring the state government to boycott all Israelis/Iranians then this would override the previous prohibition.

PS: And even if 0bama got this passed as a treaty or statute, that would remain the same. States would still be free not to trade with Iran, or with companies that trade with Iran. Congress can’t tell states what to do with their own money.

The problem is our sanctions are on nothing. We haven’t done any business with Iran since 1979; there is nothing to block.

Similarly, the few foreign companies which might run afoul of US or State sanctions can just set up a separate entity to do business with Iran.

– –

But even this is an unlikely eventuality. The only industry which might actually be materially affected would be banking (in a few years the oil services industry might possibly come into play). The main banking states are blue; only North Carolina and Texas might have any noticeable effect at all. And that effect would likely just be temporary inconvenience.

– –

Bottom line: the Presidency is a powerful position. Not only does it control most foreign policy decisions, appoint the leadership of all federal agencies, and put an average of 100 judges on the federal bench for life terms every year, but it has powers to wield in many other ways. Some are clearly legal, some not – but hard to stop without 2/3 of the Senate.

Elections matter. We made terrible mistakes in ’08 and ’12. In neither year did we have an ideal nominee, but the last one of those we saw was Reagan 32 years ago. Losing to Democrats means a big loss not just for the GOP, but for the country, and the world.

The states would be boycotting, not sanctioning, so it doesn’t really matter where an industry is located. If enough large states say they won’t invest in companies that do business with Iran, and won’t allow localities in their states to do so either, this may have an impact.

Also, NY is a blue state, but very pro-Israel and anti-Iran, and it shouldn’t be hard to get both the state and the city to put pressure on banks to make it difficult to do business with Iran, though they can’t ban it outright.

No, there are a lot of financial sanctions (imposed by the federal government, not the states) which are very powerful.

They are especially powerful since banks and other financial institutions are afraid of inadvertantly breaking them, and finding themselves sanctioned.

They are so powerful that the agreement actually contains a clause declaring that the U.S will do something to make sure that the lifting of sanctions actually works!

https://www.justsecurity.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/271545626-Iran-Deal-Text.pdf

As a result of the fact that some sanctions will remain, and that the United States can cause other countries to in effect carry out some kind of sanctions that they did not impose themselves, and the fact that the United States could impose sanctions for other reasons, Iran could probably declare the agreement to have been violated at any time, without even getting too much of an argument.

1. Those are the federal sanctions, which 0bama is going to waive unless opponents can muster 2/3 of each house to stop him. Therefore they are off topic in this thread, which is about what states can do.

2. The JCPOA requires the USA to do all these things to make sure there are no sanctions, but Resolution 2231 does not. Therefore the USA is under no obligation whatsoever to comply with that provision of the JCPOA.

Two Illinois Senators, Two Disparate Views of the “Death to America” Iran Deal

http://kingdomventurers.com/2015/07/28/two-illinois-senators-two-disparate-views-of-the-death-to-america-iran-deal/

Two points worth making.

1) If a state imposes sanctions, Iran could conceivably say that the United States is in breach of its obligations and threaten to back out. (Paragraph 37 or 26 in the Access section) It doesn’t need to be an obvious breach by the United States, it just needs to be close enough that Iran could interpret the terms of the JCPOA in its favor.

2) Still what Iran wants access to is SWIFT. Once it gets that state sanctions could be an annoyance but the battle will be lost.

Iran backing out, thus undoing the whole deal, is what we want, isn’t it? Let them back out as soon as possible, preferably before the sanctions are lifted, but if not then as soon as possible thereafter, so they can be automatically replaced 30 days after the USA notifies the Security Council of this.

Which idiot keeps downvoting everything I write, without having any argument against it? Come on, you coward. Explain yourself. If you think I’m wrong explain why, and make a fool of yourself.