SCOTUS Is Unanimous: Warrants Needed for Cellphones

Today’s court ruling one of the most high-tech of our time

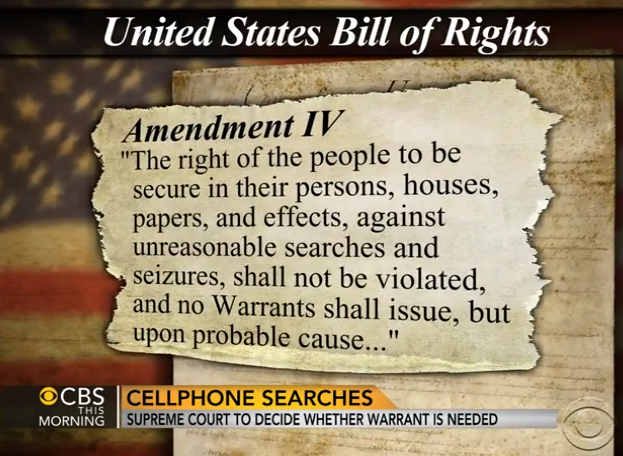

The United States Supreme Court unanimously ruled this morning that police may not search the cellphones of criminal suspects upon arrest without a separate warrant. This ruling is a huge boost for individual privacy rights advocates.

Some of the decision is excerpted below, and we will update this post with analysis throughout the day.

By a 9-0 vote, the justices said smart phones and other electronic devices were not in the same category as wallets, briefcases, and vehicles — all currently subject to limited initial examination by law enforcement. Generally such searches are permitted if there is “probable cause” that a crime has been committed, to ensure officers’ safety and prevent destruction of evidence.

Chief Justice John Roberts wrote the opinion in Riley v. California and Justice Antonin Scalia agreed with the majority but wrote a concurring opinion.

In the ruling Roberts strongly cited the Fourth Amendment’s protection of an individual rights and the advances of technology that the cellphone represents.

We cannot deny that our decision today will have an impact on the ability of law enforcement to combat crime. Cell phones have become important tools in facilitating coordination and communication among members of criminal enterprises, and can provide valuable incriminating information about dangerous criminals. Privacy comes at a cost.

Our cases have recognized that the Fourth Amendment was the founding generation’s response to the reviled “general warrants” and “writs of assistance” of the colonial era, which allowed British officers to rummage through homes in an unrestrained search for evidence of criminal activity. Opposition to such searches was in fact one of the driving forces behind the Revolution itself. In 1761, the patriot James Otis delivered a speech in Boston denouncing the use of writs of assistance. A young John Adams was there, and he would later write that “[e]very man of a crowded audience appeared to me to go away, as I did, ready to take arms against writs of assistance.” According to Adams, Otis’s speech was “the first scene of the first act of opposition to the arbitrary claims of Great Britain. Then and there the child Independence was born.”

Modern cell phones are not just another technological convenience. With all they contain and all they may reveal, they hold for many Americans “the privacies of life,” Boyd, supra, at 630. The fact that technology now allows an individual to carry such information in his hand does not make the information any less worthy of the protection for which the Founders fought. Our answer to the question of what police must do before searching a cell phone seized incident to an arrest is accordingly simple— get a warrant.

Interestingly, the Riley opinion goes into great detail about how our modern technology, specifically cellphones, have centralized most all of a person’s life’s information on a cellphone. The Court noted that even after a warrant, the government having one’s cellphone its still because even more information can be discovered later including saved passwords, bank account information, etc.

DONATE

DONATE

Donations tax deductible

to the full extent allowed by law.

Comments

This makes me happy.

I’m very glad that a certain cop that writes at another site is going to be all butthurt about it as well.

Interestingly enough, the Fourth Amendment does not protect your communications in general. The drafters were prodigious letter-writers; they certainly could have protected your letters if they had wanted to, and from letters, your phone communications would be an obvious extension, along with telegrams, faxes, e-mails, etc. But lacking Constitutional protection for your letters, it’s hard to see protection of your phone, as a communications device, being a Constitutional issue. The key concept here seems to be that your phone can have a great deal of personal information on it, making it conceptually part of your “papers”, rather than just a communications device. And as part of your “papers” it is protected.

Interesting chain of reasoning. And apparently pretty compelling, if all nine of them signed on.

Can you provide some case law for …

The text of the Fourth Amendment protects papers:

Your letters have never been protected, at least while it’s “mail” – that is, in transit. Once received and dumped in a box somewhere, they arguably become part of your “papers”. But while en route, no. The Postmaster General and his minions have the specific right – or, sometimes, duty – to examine your mail.

According to the US Postal Service:

Once again, can you provide some case-law?

This is great. Rummaging through a cell phone without a warrant is no better than breaking the seal on a sealed letter circa 1795 without a warrant. At least make people work a little bit. It’s not as if judges won’t hand the warrants out like candy anyway, but at least there’s some tiny speed bump preventing doing this on a mass scale.

Except at international borders of course. But that’s separate.

What if the police officer is conducting a search incident to a lawful arrest for drug dealing. He has the cell phone in his hand, and it rings. Can he answer it? Can he look at the display to seek who’s calling?

This specific issue was addressed in United States v Wurie petition. The answer is a resounding NO!!!. Warrant first except under exigent circumstances.

Ow wow. Sounds like Wurie basically says you cannot use a phone as a means if identification.

Does that mean cops can’t open you wallet and check your drivers license?

Let me clarify, it seems to mean that police cannot examine a persons phone as a means of identification.

These consolidated rulings give one clear message: get a search warrant. The Court leaves in place the very narrow exigent circumstances exception. It explicitly refuses to even apply the Gant exception. Gant allows warrantless searches for specific evidence related to the crime the person in a car is being arrested for. For example prior to today, under Gant a police officer making a reckless driving arrest could have used Gant to support searching a cell phone for text messages to prove the person was texting.

The view of the Court is that your life may be on the cell phone and almost any search is too intrusive absent a warrant.

The Court also addressed your wallet concern:

I was thinking this over yesterday and I’d like to ask:

If a policeman pulls me over because he thinks I’ve been texting while driving, can I refuse to provide my phone for him to view?

Prior to yesterday’s ruling, Arizona v Gant allowed the police to search for evidence related to the crime the person was being arrested for.

Funny, I did discuss that very issue with some local officers this morning. They all said they would never go so far as to insist on seeing a cell phone for something so minor as a texting ticket.

If you face an officer who would go that far, there are practical considerations. He is not as well trained or predictable as the officers I spoke with, or the police suspect you of some other crime. In theory he could charge you with obstruction of justice. You could then be subjected to a custodial arrest. At that point, you are looking at legal fees far in excess of the fine for texting.

Under yesterday’s ruling, the policeman still retains the right to seize the cell phone and obtain a search warrant (extreme for something so minor).

Good outcome. Police should have a legal reason for everything they search, especially the evidentiary treasure trove that is a smart phone.

[…] unanimous SCOTUS […]

The Fourth Amendment: it says what it means and it means what it says.