Federal Appeals Court Hears Challenge to Trump Tariffs

The court questioned whether the authority to “regulate . . . importation” necessarily includes the authority to impose tariffs of unlimited size and duration.

A federal appeals court on Thursday heard arguments in a case challenging the Trump administration’s tariff regime.

The arguments in V.O.S. Selection, Inc. v. Trump focused on whether President Donald Trump exceeded his authority under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) by issuing tariffs to prevent human and drug trafficking and to remedy international trade imbalances.

IEEPA authorizes the president to “to deal with any unusual and extraordinary threat” by giving him the authority to “regulate . . . importation.” Oral argument focused on whether IEEPA, which does not expressly mention tariffs, impliedly confers the authority to impose tariffs under the guise of “regulat[ing] . . . importation.”

The Liberty Justice Center represents several small “businesses who have been severely harmed by the tariffs and highlights the human and economic toll of unchecked executive power.” The businesses argue Trump exceeded his authority by imposing the “Liberation Day” tariffs.

The administration appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit after a three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of International Trade (CIT) unanimously ruled that Trump exceeded his authority by imposing the tariffs.

Judges of the Federal Circuit questioned the parties about the Trading with the Enemy Act (TWEA), a law predating IEEPA from which IEEPA borrowed the “regulate . . . importation” language.

In U.S. v. Yoshida Int’l. Inc. (1975), the U.S. Court of Customs and Patent Appeals—the Federal Circuit’s predecessor court—held that TWEA allowed President Richard Nixon to impose limited tariffs to address a monetary crisis in 1971.

Nixon limited the tariffs to those authorized by the Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States at the time. The Yoshida court upheld the tariffs because Nixon “imposed a limited surcharge, as a temporary measure calculated to help meet a particular national emergency, which is quite different from imposing whatever tariff rates he deems desirable.”

After Yoshida, Congress enacted IEEPA.

An attorney for the administration noted Congress was aware of Yoshida when it enacted IEEPA by copying language from TWEA. This, he contended, meant Congress intended to “ratify” Yoshida and grant the president tariff authority during an emergency.

The judges repeatedly pushed back, arguing that if Congress ratified Yoshida with IEEPA, then Congress must also have ratified the limits in Yoshida. The administration’s attorney contended that IEEPA did not necessarily ratify the limits of Yoshida since IEEPA contains its own list of limitations, including a presidential declaration of a national emergency.

Oral argument also focused on what constitutes an “unusual and extraordinary threat,” with several judges and the challengers questioning whether a longstanding issue like a trade imbalance was “unusual” or “extraordinary.”

The Tariffs

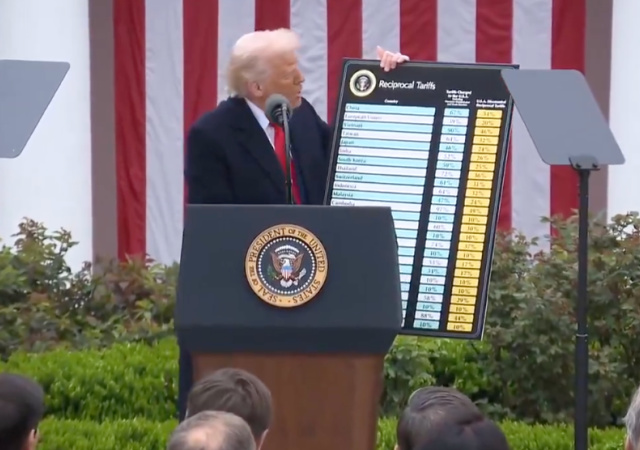

Trump imposed the Worldwide and Retaliatory Tariffs (EO 14257) to remedy persistent trade deficits between the United States and other nations. EO 14257 imposed a 10% ad valorem duty on “all imports from all trading partners,” except a few nations expressly excluded.

China responded by increasing tariffs on U.S. goods, leading Trump to impose retaliatory tariffs of 84% to 125% on Chinese goods. China later took “a significant step . . . toward remedying non-reciprocal trade agreements,” after which Trump reduced tariffs on the nation to the original 10%.

Trump imposed the Trafficking Tariffs (EO 14193, EO 14194, EO 14195) to induce Canada, Mexico, and China to stem the flow of trafficking in people and narcotics. The tariffs imposed a 25% ad valorem duty on articles from Canada and Mexico, a 10% (later 20%) ad valorem duty on articles from China, and a further 10% ad valorem duty on Canadian energy and energy resources.

After finding Mexico and Canada acted “to alleviate the illegal migration and illicit drug crisis through cooperative actions,” Trump paused the tariffs.

Meaning of “regulate . . . importation”

The CIT’s decision interpreted the meaning of “regulate . . . importation” found in §1702 of IEEPA, which the administration relied on to support its tariffs.

The plaintiffs argued that the authority to “regulate . . . importation” did not extend to imposing tariffs. Interpreting the phrase otherwise, the plaintiffs argued, would violate the non-delegation and major questions doctrines.

The non-delegation doctrine stems from the constitutional mandate that legislative powers are vested in Congress. When Congress delegates some of its powers to another branch—like the Executive—the delegation must come with “an intelligible principle” governing the exercise of that power and the scope of the delegation. Such a principle must place a meaningful constraint on the president’s authority.

The major questions doctrine also governs the delegation of legislative power where matters of far-reaching economic and political significance are concerned. The doctrine requires that when Congress wishes to delegate the power to deal with these matters, Congress must unambiguously delegate that power.

The administration countered that “regulate . . . importation” should “have the same meaning” it did in TWEA, which allowed the president to impose tariffs.

The administration disagreed that IEEPA contained no limiting “intelligible principle” since it requires the president to declare a national emergency, which expires after a year. IEEPA further requires that the emergency must pertain to an “unusual and extraordinary threat” and that the power to “regulate . . . importation” extends only to a foreign country’s property or property in which a non-American has an interest.

The CIT agreed with the plaintiffs that “regulate . . . importation” could not encompass tariffs as far-reaching as the Worldwide and Retaliatory Tariffs without running afoul of the non-delegation and major questions doctrines.

The CIT held that IEEPA confers a narrow authority to “regulate . . . importation.” Looking to the congressional record, the CIT found that Congress intended to restrict the president’s tariff power:

In enacting reform legislation including IEEPA, Representative John Bingham, Chair of the House International Relations Committee’s Subcommittee on Economic Policy, described TWEA as conferring “on the president what could have been dictatorial powers that he could have used without any restraint by the Congress.” Similarly, the House report on the reform legislation called TWEA “essentially an unlimited grant of authority for the President to exercise, at his discretion, broad powers in both the domestic and international economic arena, without congressional review.” (citations omitted)

“Congress,” the CIT determined, “reformed the President’s emergency powers in part by enacting IEEPA to provide the President a new set of authorities for use in time of national emergency which are both more limited in scope than those of the Trading with the Enemy Act and subject to various procedural limitations, including those of the National Emergencies Act.” (cleaned up)

The president’s authority to impose tariffs to address trade imbalances, the CIT reasoned, is cabined to the more limited statutes that impose limits on the percentage and duration of tariffs.

How to “deal with” a threat?

The CIT also addressed whether the Trafficking Tariffs “deal with any unusual and extraordinary threat” as required by §1701 of IEEPA. The three-judge panel held those tariffs did not fit the ordinary meaning of “deal with”:

“Deal with” connotes a direct link between an act and the problem it purports to address. A tax deals with a budget deficit by raising revenue. A dam deals with flooding by holding back a river. But there is no such association between the act of imposing a tariff and the “unusual and extraordinary threat[s]” that the Trafficking Orders purport to combat. Customs’s collection of tariffs on lawful imports does not evidently relate to foreign governments’ efforts “to arrest, seize, detain, or otherwise intercept” bad actors within their respective jurisdictions.. (citation omitted)

The CIT, in a footnote, expounded on the lack of a direct link: “The Trafficking Tariffs, of course, do not change the effective rate of duty (zero percent ad valorem) for smuggled drugs themselves.”

The CIT opinion:

Donations tax deductible

to the full extent allowed by law.

Comments

When did regime and regimen become interchangeable words?

Centuries ago. They both have the same Latin origin and have both been in use in English for more than 500 years, more or less interchangeably. The convention to use regime for governments and regimen for systems of control only exists in the USA, and even here it’s only a tendency, not a universal rule. In the rest of the English-speaking world regimen is seldom used, and regime is routinely used for all senses of the word.

Terrance Kible lives in Pittsburgh, so his use of regime here is slightly unusual, but not overly so. I’m surprised you haven’t come across it before.

No standing

What are you talking about? The plaintiffs are directly affected by these probably-illegal tariffs, and have all the standing in the world to challenge them.

The Liberty Justice Center is a very respected public-interest law firm on our side, and is responsible for the Supreme Court’s wonderful decision in Janus that we all (and I would hope you too) welcomed in 2018.

So were we in the election of 2020, but they literally “ruled “ we, the people, had no standing in election of our President

Texas has no standing on how Pennsylvania chooses its electors. That is entirely a matter for Pennsylvania. Texas chooses its own electors however it likes, and that’s all the say it’s entitled to.

Here these small businesses are being taxed, and it’s destroying them! How can they not have standing????

texas and the rest wanted the supreme court to look at the fact that PA violated its own rules when it allowed :::

The U.S. Supreme Court said Monday that election officials in Pennsylvania can count absentee ballots received as late as the Friday after Election Day so long as they are postmarked by Nov. 3.

The court declined without comment to take up one of the highest-profile election law cases in the final stretch before Election Day. Pennsylvania Republicans had sought to block the counting of late-arriving ballots, which the state’s Supreme Court had approved last month.

Republicans sought the emergency stay, arguing that it is up to the state’s legislature — not the court — to set rules for how elections are conducted. They also said the court’s ruling could allow ballots cast after Election Day to be counted.

as as we know it was roberts who sided with the leftys and said no

we wont take a look

https://www.npr.org/2020/10/19/922411176/supreme-court-rules-pennsylvania-can-count-ballots-received-after-election-day

I don’t know about anybody else, but somebody that wants to sabotage their own negotiator in the middle of negotiations, I’d call that person a traitor

What do you mean by “their own negotiator”? Trump is not acting for them, and is acting completely against their interest. Since there are grounds to believe that he’s breaking the law in doing so, why should they not sue him and try to make him stop?

The entire idea that trade deficits are a bad thing, that governments should try to prevent, is left-wing economics and something that conservatives have fought against for 200 years. The plaintiffs certainly have no interest in reducing the USA’s trade deficits with various countries, and have not consented to having their livelihoods and businesses destroyed in that cause. If this were a Democrat president doing this you’d be on their side. But because it’s Trump you call them traitors?!

Because shit like this is virtually helping your enemies to undermine your own country 🙄

Thanks for the above. I for one am tiring of the accusation of “Traitors” being bandied about anytime anyone raises well thought out opposition to something Trump does or proposes.

Did you have this same view when Biden illegally allowed many illegal aliens into the country and allowed many foreigners to take advantage of America?

There is no one more anti-American than an American.

Which view would that be? That the word “treason” shouldn’t be bandied about whenever a person objects in a reasonable manner to a presidential proposal or policy they disagree with? Why yes, that opinion does not depend on who is in the W.H. What that has to do with Biden’s illegal actions I don’t know. I can object to both.

“Well thought out opposition to something Trump does” does not exist 😂😂

We regularly say we want judges to call it based on the law, not based on their preferred policies. Well, if the law says the President cannot impose these tariffs, it shouldn’t – at least I think it shouldn’t – matter what effect that has on his negotiations.

Of course, I’m assuming in this case that the judges are making the correct call on the law. I’m not an expert, and have seen some contrary opinions. Still, based on what I do know about it, I’m inclined to think they are correct in this. I can definitely say it seems justified, not some out-there political vendetta (which we have seen from some judges, to be fair.)

The law doesn’t say he can’t impose tariffs. It gives the POTUS the authority to “regulate…importation,” which can be interpreted to mean “impose tariffs” because tariffs can be, and are, used to “regulate importation.” The argument being made by the plaintiffs is that the law’s “regulate importation” doesn’t include tariffs.

I’d like to know what they think is does mean. It must mean 1.) the exercise of some authority otherwise reserved to Congress; and 2.) the exercise must be Constitutional (that is, the same restraints on Congress apply to the POTUS when Congress delegates some portion of its authority to the POTUS). This doesn’t leave much if it doesn’t include tariffs.

I don’t think they completely thought through basing their argument on non-delegation. Are they ready to end most of the regulatory state?

First of all, yes, they would be delighted to do that if they could. But they can’t, so they’re not trying to do that. The non-delegation doctrine obviously does allow the regulatory state, or else that state wouldn’t exist! It would have been struck down long ago.

But the doctrine allows delegation so long as there’s an intelligible principle limiting the authority delegated. Regulations have in fact been struck down for lack of such a limit.

Here there doesn’t seem to be any limit at all. Trump is arguing that the mere fact that he has to go through the motions of declaring an emergency first is enough of a limit! The “intelligible principle” he discerns is merely “declare an emergency, and then you can do whatever you like; every time it expires, declare it again, and you can do whatever you like forever”! That’s not a limit, it’s a carte blanche delegation of authority, and that’s unconstitutional.

Tiresome.

What do you find tiresome? The truth?! You’re the one who raised the issue of the regulatory state, smug in your utterly baseless assumption that the plaintiffs and their lawyers have any interest in maintaining that, and wouldn’t want to undermine it. Now you suddenly find the facts tiresome because they don’t conform with your assumption?! Or what?

tiresome indeed.

The power to ‘regulate imports’ would seem to have to include lesser/intermediate tariffs b/c one surefire way of ‘regulating imports’ would be to bar imports from a particular Nation entirely on a temporary basis during a conflict or preemptively as tool to avoid/deter conflict. Granting the Executive powers/tools that can be viewed as additional arrows in the quiver of National Security and Foreign Policy is dangerous b/c those responsibilities are the apex of Executive powers. The question here isn’t whether the policy using the power is ‘good’ or whether iy was wise to grant the powers but whether the Congress granted it and IMO they did.

And what of the major questions doctrine? If you seriously think Congress meant to grant the president such sweeping power, shouldn’t it have said so? What did it think it was doing, stuffing an elephant in a mousehole?

And even if it did mean to grant the president absolute and unlimited authority over all imports, how could it do so? How would that not violate the non-delegation doctrine?

FWIW – my initial take is that

A – The major question doctrine would apply and

B – the holding would be that congress did not give the president the authority to impose unilateral tariffs of the current magnitude.

Similar to the major question doctrine that would hold that congress did not give biden the authority for wholesale student loan forgiveness , or nation wide covid lockdowns, rent eviction moritoriams, etc

just to clarify on the major question doctrine

Congress did give the president authority to forgive student loans, though not the authority for the wholesale forgiveness of student loans.

To be fair, Congress has a long history of writing legislation that grants the deep state, the president, or other parties substantial power and leeway. This particular bit of legislation, the IEEPA, appears to be no different. Congress granted the President the power to use tariffs and tariff rules to protect the interests of the country as the President would see it, precisely as it is intimately involved with foreign policy and the President is (by design) the architect of that.

No doubt there are people here who would wish to require Congress to be specific in all things; there are times when leeway is needed. I would interpret IEEPA in that way and find (if I were a justice) that the President didn’t exceed the authority Congress gave him. Should Congress be doing that? That’s a political question.

You make great points and I’d be far more accepting of them if they were applied consistently. I don’t see the argument for the major questions doctrine (which is in any event a judicial creation) as being at odds with my argument about WHETHER the Congress made the grant of power and in doing so gave the Executive too much power b/c this grant fits very neatly within apex powers of National Security and Foreign Policy.

It would be very fair to argue that the Congress CANNOT make such a grant and cite major questions doctrine. IMO it would be absurd to seek to invoke the non delegation doctrine given the context of Congressional grants of authority to the Executive in the last 100 years or so and seek to apply it here. That wouldn’t be a good faith argument.

We come back to a question of should v may. Congress does a great many things that are outside of its specific enumerated powers will be be rolling those back as well? Given the great many very dubious but sweeping grants and delegations of power to the Executive by successive Congress (often assuming powers not specifically granted to it) it is hypocritical to seek to apply limiting doctrines here but not elsewhere. Everyone can offer their own contrary opinions to mine but as we aren’t Judges or advocates for either party we aren’t making legal arguments but rather offering our own opinions and are unbound by any limits to a ‘case or controversy’ before the court.

I’d be far more accepting of them if they were applied consistently

^^THIS^^

oops accidently hit the down vote – millhouse’s analysis is reasonably correct.

Likewise if it didn’t intend to grant the POTUS such authority, why doesn’t the language of the delegation include explicit limits that rule out such exercises of authority? Or why isn’t the language of the delegation more clear such that it would preclude the use of undelegated authority?

I posted this on another site when someone brought up the Stafford Act which I refer to in the first sentence.

“Then you know a major part of the act (which covers natural disasters and catastrophes, not trade policy) is that a state must first request assistance. They basically have to exhaust their resources for dealing with the disaster and realize they can’t handle further response without federal assistance. The president decides whether the state is eligible and declare an emergency if he decides they are.

That really is not what is happening here. As far as I know no state (in favor of tariffs or not) has requested the President to declare such an emergency after exhausting their own resources for dealing with unfair trade practices by foreign nations.

The question presented to the court is whether the “International Emergency Economic Powers Act” is broad enough to cover Trump’s declaring tariffs. At least that is my understanding of the government’s argument.

Reading the act I don’t see how it could be stretched to cover tariffs. Keep in mind the act comes under the Federal USC Title 50 “War and National Defense.” I suppose it could be presented that these tariffs serve the same purpose as economic sanctions mentioned in the act and therefore should be considered as meeting the intentions of the act.

Yet then I come again to this all coming under “War and National Defense” which explains why the act is very clear about which nations or groups are subject to sanctions and what is exempt from those sanctions.”

““Deal with” connotes a direct link between an act and the problem it purports to address.”

This is where I think the CIT erred. The Trafficking Tariffs did act directly on the behavior of the offending countries and caused a desired behavior change. That’s as direct as it gets. Their definition is semantic game playing.