American History Tour: Wilson’s Creek Battlefield

The second battle of the Civil War which kept southwestern Missouri in the hands of the Confederacy.

I’m addicted to battlefields after the two-week road trip to Boston. I decided to drive home to Chicago instead of flying so I could visit some battlefields along the way.

Republic, MO, is home to Wilson’s Creek, the place of the Civil War’s second battle and the first west of the Mississippi. The Confederates won while the Union lost its first general, Gen. Nathaniel Lyon.

Lyon’s forces camped in Springfield, MO. Brig. Gen. Ben McCulloch brought Confederate forces from Arknasas and Maj. Gen. Sterling Prie had forces southwest of Springfield.

5,400 Union soldiers. 11,000 Confederates.

Wilson’s Creek took place on August 10, 1861 for only six hours.

However, the Union and Confederacy fought for three years for control of Missouri.

The driving tour included eight spots. For the majority of them, you had to walk to the main attraction, which isn’t always viable for someone with rheumatoid arthritis. I apologize in advance if I don’t have many pictures of the top spots.

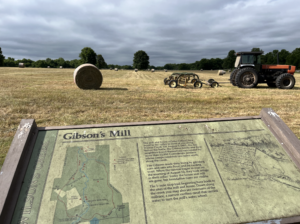

The first stop is Gibson’s Mill, which is over a mile from the parking spot. I could not make it to the farm or mill but the pictures are of the Gibson’s oatfield.

Missouri State Guard Gen. James Rains camped his Confederate soldiers near the mill. Lyons attacked the Confederates, also ordering Capt. Joseph Plummer to cross the creek and attack. The fighting pushed the Confederates to the creek.

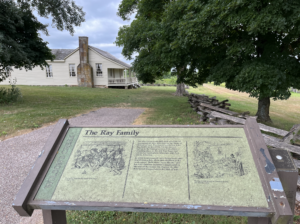

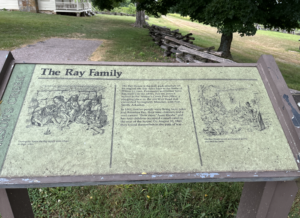

The Ray House and Cornfield play two parts in the battle. Twelve people lived in the house while a slave and her four children lived in a shed in the back. The house was not open so we could not go inside. It’s the only original structure on the battlefield from that time.

You can learn more about the Ray family at this website.

The Confederates used the house as a hospital for the battle. The family would take shelter in the cellar during the fighting while John Ray watched from the porch.

The only fighting at this part of the battle took place in the cornfield. It is part of the area Plummer’s forces had to go through when the Confederates pushed them back across the stream.

The second part happened at the end. The Union took Lyons to the Ray House after he as killed.

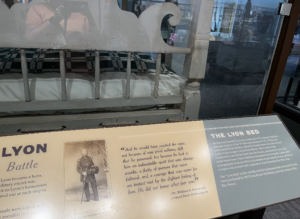

The bed Lyon died on is at the Visitor Center.

It took too long to get to Pulaski’s Arkansas Battery ([lus up a steep hill..not good for my knee joints!) but it is the third spot along with Maj. Gen. Sterling Price’s headaquarters near the William Edwards cabin.

The Pulaski Arkansas Battery is from Pulaski County, Arkansas. The area I could not reach is where the battery opened fire on Lyons’ soldiers as they advanced on Bloody Hill.

The attack allowed Price to gather and form their men close to the Edwards cabin.

The picture I have is the field for William Edwards where Price and others organized the Confederate men.

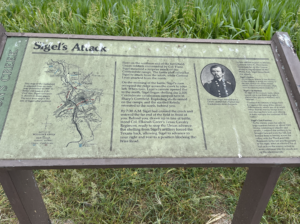

The fourth spot belongs to Col. Franz Sigel held his second position. It’s also where Sigel’s Union artillery heard Lyon’s attack.

The soldiers opened fire on the 1,800 Southern Calvary. In this spot Sigel formed his men into a line. The Confederates eventually withdrew from this spot.

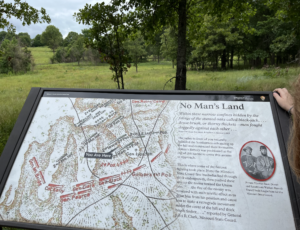

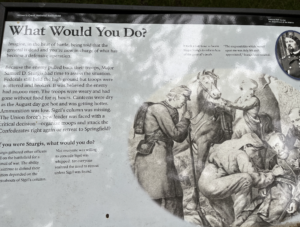

But then Sigel made a fatal error at the fifth spot known as Sigel’s Final Position. Sigel thought the troops in front of him belonged to the Union.

It ws a Confederate line. They opened fire on Sigel and defeated him.

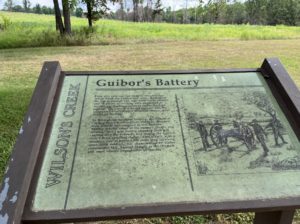

Capt. Henry Guibor placed his bettery at the sixth spot. Guibor battled with the Union army right at the border of Bloody Hill.

The Union managed to hold its spot against Guibor.

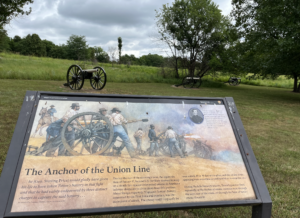

Bloody Hill. This is where Lyon tried to defeat the Confederates all day. This is where the Confederates aimed their batteries from the other spots. The NPS has a description and it’s worth a read:

On the morning of August 10, 1861, Union and Southern forces met at Wilson’s Creek in the second major battle of the Civil War. Called the “Bull Run of the West,” some of the battle’s most pivotal moments occurred on high ground later christened “Bloody Hill.”

Around 5:00 am on August 10, 1861, fighting started. Troops under Union Brigadier General Nathanial Lyon moved to an area of high ground that would earn a new name that day – Bloody Hill. Over the next six hours, the battle’s most intense and savage combat took place here as Lyon’s men braved artillery fire from the Pulaski Arkansas Battery and faced several Southern attacks.

Fighting intensified around 9:00 a.m., when Major General Sterling Price and his pro-secessionist Missouri State Guard began a second assault. Southern troops formed three or four ranks deep and fired while lying down, kneeling, and standing. For more than an hour, they faced Lyon’s 3,500 men and 10 cannon at close range. As black powder smoke hung thick, men fired blindly. The blistering August heat took its own toll and men fell to heat exhaustion as well as bullets and cannon fire.

As the battle raged, Lyon remarked to his chief of staff, Major John Schofield, “It is as I expected. Major, I am afraid the day is lost.” Schofield replied, “No, General; let us try it again!” Spurred on by Schofield’s enthusiasm, Lyon rode toward the center of the fighting. He began repositioning his troops. Waving his hat in the air, Lyon reportedly cried, “Come on, my brave boys, I will lead you! Forward!”

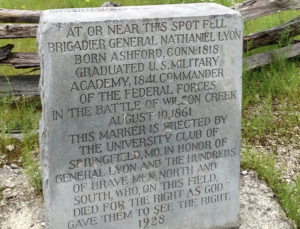

Just then the Confederates let loose a volley of fire. Lyon fell from his horse with an instantly fatal wound in the chest. With his death, Lyon became the first Union general killed in combat during the Civil War.

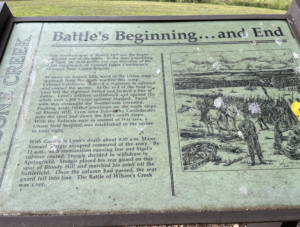

The third and largest Southern assault against Bloody Hill began after Lyon’s death, but ended in failure as the Southerners fell back. Union Major Samuel Sturgis, in command after Lyon’s death, ordered his troops to retreat because of heavy casualties, dwindling ammunition and no relief in sight from other Union forces. The Southerners, disorganized and also low on ammunition, did not to pursue. The battle of Wilson’s Creek was over, a tactical victory for the South.

The spot includes a sinkhole that contained 30 dead Union sodiers. They were eventually laid to rest in Springfield.

The picture I took of the Lyon marker did not turn out so I used the one from the NPS. Apologies.

Maj. Samuel D. Sturgis replaced Lyon.

The last spot on the tour should also be the first spot. The Historic Overlook is the route of the Union advance and withdrawal.

It is where the battle started and where the Union went before withdrawing to Springfield. Sturgis knew his men were tired and had almost no ammunition. The Confederates did not pursue because they also did not have enough ammunition. They were also disorganized.

16,400 soldiers engaged in Wilson’s Creek.

The Union had 1,235 casualties. The Confederacy had 1,095 casualties.

The Confederates kept southwestern Missouri.

Donations tax deductible

to the full extent allowed by law.

Comments

Thanks again Mary… opening my eyes about the civil war.. and I loved all the photos… The sink hole kinda got to me…

You’re welcome! I’m going to Pea Ridge on the way back.

Spoiling the rebel advance ended up being so crucial. Price and McCulloch were petty and refused to submit to the other. This resulted in losing their toehold and NW Arkansas. Jefferson Davis had to send a senior general to try and save Missouri at the turn of 1862 in Van Dorn, leading to Pea Ridge.

Without this seemingly inconsequential action, the rebel advance might have made a serious threat on the loyal government in St Louis.

The MSG and Confederate regular forces didn’t seem to get along much at this battle–Price and McCulloch were in effect “co commanders,” which didn’t help much with coordination. On top of that, the MSG were ill-armed and ill-disciplined compared to the CS regulars under Pearce and McCulloch.

But it was a key battle. Despite the Union defeat, as you point out, it stymied CS efforts in the area at least for the short term.

Yup. I’m going to Pea Ridge on the way home. It took place in 1862. Even though it’s in Arkansas it helped keep Missouri in the Union. I’ll write that one up as well!

If you ever desire to see the living Civil War, go to VMI. Every Fridan, weather permitting, the cadets parade. Their uniforms are what was the style in 1860 and are what they wear to class. The attrition rate at the school is about 30% as the students are not treated in the same manner as at other military schools and again is more typical of the 1800s. All who graduate get a job and most go directly into the military. If you are lucky or call ahead, you can catch the New Market celebration which will cause emotions.

Thanks! I’ll have to do that.

Thanks, Mary for this. Many think of and have visited the “Big Ones” but men of both sides died on many battlefields. Fight in the cornfield brings home what was going on and how terrible it was. Brother against brother across cornfields, hayfields, creeks, roads and on horseback.

Another fantastic history lesson, thanks