Family Discovers Rare Thomas Jefferson Letter in Attic

“We must sacrifice the last dollar and drop of blood to rid us of that badge of slavery…”

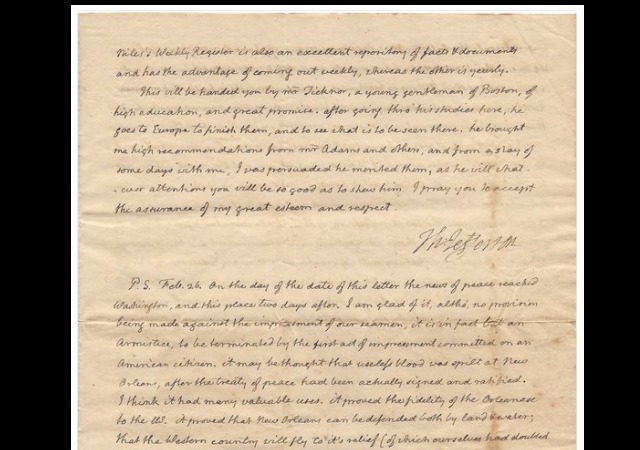

A family found a letter from Thomas Jefferson from 1815 to the U.S. Ambassador to France about the victory in the War of 1812:

“As in the Revolutionary War, [the British] conquests were never more than of the spot on which their army stood, never extended beyond the range of their cannon shot,” Jefferson wrote in the letter, penned at his Monticello home on Valentine’s Day, 1815. “We owe to their past follies and wrong the incalculable advantage of being made independent of them. . . ”

Raab in @FoxNews To read about the country’s independence from Jefferson's pen is incredible https://t.co/lHOLOG7cPt pic.twitter.com/JeFysUeOqj

— The Raab Collection (@RaabCollection) July 5, 2016

The Raab Collection has priced the document at $325,000:

“This kind of letter is only seen up for sale once a decade, if not once a generation,” Nathan Raab told FoxNews.com. “You just never see this for purchase by the public. These types of letters that are owned by direct descendants are usually donated to private collections.”

In the letter, Jefferson railed against the British and propped up future president Andrew Jackson’s victory at New Orleans to Ambassador William Crawford:

“We must sacrifice the last dollar and drop of blood to rid us of that badge of slavery, and it must rest with England alone to say whether it is worth eternal war, for eternal it must be if she holds to the wrong.”

Jefferson noted future president Gen. Andrew Jackson’s seminal victory at the Battle of New Orleans — the final battle of the War of 1812 — that led to America’s victory.

“It proved. . . that New Orleans can be defended both by land & water; that the Western country will fly to its relief . . . that our militias are heroes when they have heroes to lead them on,” he wrote.

Jefferson also comments on Napoleon’s demise and how it eventually worked to America’s advantage.

“[His] downfall was illy timed for us,” he said. “It gave to England an opportunity to turn full handed on us, when we were unprepared. No matter. We can beat her on our own soil . . .”

The War of 1812 actually lasted until February 18, 1815, and included the capture and destruction of our capital. Some even celebrated the end of the war as a “second war of independence.”

The British started the war since they attempted to “restrict U.S. trade, the Royal Navy’s impressment of American seamen and America’s desire to expand its territory.” At the time, England faced battles with France, who helped us win our independence from the crown. Great Britain wanted neutral countries “to obtain a license from its authorities before trading with France or French colonies.” The Royal Navy ticked off America even more when they removed “seamen from U.S. merchant vessels and forcing them to serve on behalf of the British.”

[Featured image via Twitter]

Donations tax deductible

to the full extent allowed by law.

Comments

How do thse things survive, and yet remain unknown? Was the letter known to a previous generation, but got lost maybe 30 to 60 years ago?

Since Thomas Jefferson made copies of all the letters he sent, the text is probably known, and has been printed. It’s just this autographed signed letter that’s new.

You are correct, the letter is indeed known. It’s in Jefferson’s collected papers, dated 14 Feb. 1815.

Imagine the treasures that have been discarded when attics are cleaned out.

When I die, you’re welcome to everything and anything that’s in my attic. The Christmas lights that don’t light up and the ugly leftover art from my grandmother’s house. On the plus side, my dad has a page from an original printed copy of a 1611 King James Bible he bought from a gentleman who obtained it from an old British lady’s attic.

at the Battle of New Orleans — the final battle of the War of 1812 — that led to America’s victory.

Both the Battle of N.O., and the U.S.S. Constitution‘s epic last fight (a scenic affair conducted partially by moonlight), occurred after the war was already over, and a signed copy of the Treaty of Ghent was already on the way to the US. Although the Treaty wouldn’t become official until ratified by those rascally Yanks, the terms of the treaty were unaffected by any events occurring late in the war, of which (of course) the negotiators would have been ignorant.

For Britain, the dreadful suffering endured by Packenham’s Highlanders as they slogged through the mud at New Orleans contributed nothing, one way or the other, aside maybe from being a black-powder dress rehearsal for similar foolishness at the Somme almost exactly a century later.

For the US, it accomplished nothing directly, but it did elevate that old Indian fighter Jackson to a prominent position on the national stage. And it arguably had something to do with the transformation of the United States from a collection of squabbling ex-colonies into a real country.