1948 – How American Jewish Pilots Helped Win Israel’s War of Independence

After winning WWII, they flew for Israel.

Memorial Day for the Fallen Soldiers of Israel and Victims of Terrorism (Yom Ha’zikaron) begins at sunset. It transitions on Wednesday evening to Israel Independence Day (Yom Ha’atzmaut).

Due to the time difference, Israelis are already honoring the 23,320 fallen soldiers and victims of terrorism since the beginning of political Zionism, among them 553 fallen with graves unknown.

Israel came to standstill Tuesday evening at 8 p.m. for a minute-long memorial siren. The siren was followed by the lighting of a memorial flame at the Western Wall (the Kotel), the site of the official state commemoration ceremony.

On Wednesday, another official ceremony will be held at the Mount Herzl military ceremony in Jerusalem. It’ll honor the 116 soldiers and former soldiers who died over the last year, 67 of them killed in this summer’s Operation Protective Edge. They have left behind 131 bereaved parents, 187 siblings, 11 widows, and 26 children, two of whom were born after their fathers died.

According to Defense Ministry estimates, some 1.5 million people will visit military cemeteries on Wednesday. Hundreds of buses will be available to the public at Mount Herzl and other military cemeteries across the country, and some 450,000 bottles of water will be distributed to mourners and visitors at the entrance to the cemeteries. Memorial Day will end abruptly at sundown on Wednesday with the start of Israel’s 67th Independence Day, ushered in with fireworks and street celebrations nationwide.

Here in the U.S. there’ll also be commemorations and celebrations nationwide, as Americans–both Jewish and non-Jewish–come together to honor the Jewish state’s fallen and celebrate Israel’s birthday.

It’s the perfect time to revisit how Israel won its independence.

The American Jews Who Helped to Win a War, and Save a People

On May 30, 1948—fifteen days after the fledgling Jewish state was invaded by the armies of five Arab nations—Milton Rubenfeld, a former stunt pilot who served in the British Royal Air Force and the U.S. Air Force in World War II, flew on a critical combat mission that stopped the advancing Iraqi army.

When his plane was hit by enemy fire, he bailed out, landing in the field of an Israeli kibbutz. Since no one at the time knew that Americans were flying for Israel in its War of Independence, Rubenfeld was mistaken for an enemy pilot by the rifle-brandishing kibbutz members. Hands raised in the air, Rubenfeld—who spoke not a word of Hebrew—identified himself to the Israelis and saved his life by shouting what little Yiddish he knew—“Gefilte fish”, “Shabbos”, and “Pesach”!

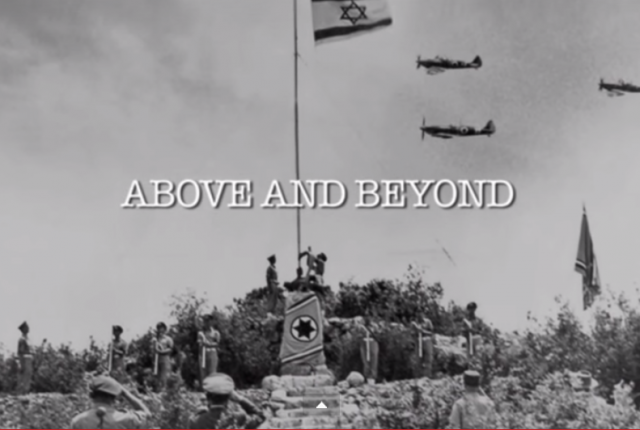

This little-known true story is recounted by Rubenfeld’s widow and his son, the actor Paul Reubens (better known as Pee-wee Herman), in a remarkable new feature-length documentary “Above and Beyond”.

Produced by Nancy Spielberg (sister of Steven Spielberg—yes, that Spielberg) and directed by the accomplished Roberta Grossman, the 87 minute film tells the fascinating tale of the American airmen who, just three years after the liberation of the Nazi death camps, volunteered with Rubenfeld in the 1948 war.

“Above and Beyond” has won rave reviews and multiple awards on the festival circuit. Opening on January 30, it’s been screening to admiring audiences nationwide.

The film is due for an April 28 VOD release including iTunes, Amazon, Google Play, and other platforms.

It features the mostly Jewish American pilots who at great personal risk smuggled planes and war materials out of the U.S., trained on old Me-109 fighters (the mainstay of the German Luftwaffe!) in secret behind the Iron Curtain in Czechoslovakia, and flew dozens of missions in the summer and fall of 1948 for the Israeli Air Force’s (IAF) newly created 101 Squadron.

In mid-May 1948 the Jewish defense forces (the Haganah) had roughly 35,000 troops, no air force, almost no artillery, and very few tanks.

There can be no doubt that the Arab armies had a major edge in weaponry.

The Israelis had nothing.

Except that they had Al Schwimmer.

Schwimmer worked for TWA and had been a flight engineer for the U.S. Transport Command in World War II. When he learned of Israel’s need for aircraft, he single-handedly bought some thirty surplus Messerschmitt fighters and recruited the pilots to fly them.

The U.S. State Department’s hostility toward the new Jewish state and the arms embargo of the entire Middle East made this a chancy business. These all had to be clandestine flights. Schwimmer formed a bogus Panamanian airline and had pilots hopscotch around the globe to get to Israel.

The U.S. government threatened to revoke the citizenship of anyone who participated in the war. But Schwimmer wouldn’t be intimidated by the “pettifoggery of Foggy Bottom”.

To evade detection by the authorities, he resorted to scouring military records for former World War II airmen in the N.Y. area with “Jewish sounding names” and sending them cryptic telegrams. Mysterious instructions for secret rendezvous would’ve included “meeting a guy with a flower in his lapel on 57th street”.

Schwimmer was indicted after the war for violating the U.S. Neutrality Act. He lost his U.S. citizenship and stayed in Israel, making a fortune as the founder of Israel Aerospace Industries. In 2001, he was pardoned by President Clinton.

“Above and Beyond” includes archived war footage and stunning aerial reenactments, accomplished with special effects created by Industrial Light and Magic, which reportedly donated its time and expertise to the project.

But the interviews with the bunch of still cocky nonagenarian airmen are by far the movie’s best parts (Nancy Spielberg noted in an interview that the youngest was 88 at the time of filming).

Reviewing the documentary for the Hollywood Reporter Frank Scheck rightly says that “the film’s heart is the interviews with the pilots themselves who recall their exploits with infectious bravado”.

With the exception of Lou Lenart, who led the IAF’s first combat mission on May 29, 1948, stopping a massive Egyptian army column less than 30 miles away from Tel Aviv (more on that below), and whose family were recent immigrants to the U.S. at the time, the pilots were all second-generation Americans who knew little about Zionism and weren’t particularly proud of their Jewishness.

What motivated these assimilated American Jews to give up their comfortable post-war lives in America and answer Israel’s call for help?

This longer trailer has more details:

Each pilot recounts the anti-Semitism he experienced growing up in 1930s and 1940s America.

And as Rabbi Yechiel Eckstein, President of the International Fellowship of Christians and Jews (IFCJ) notes, the “outrages of the Holocaust” surely also compelled them to “fight for what they knew was a just cause”.

“What changed me was knowing what Hitler did,” says one of the nine former pilots interviewed.

“I was an American, but Jews were going to fight. It’s about time,” says another.

I guess you could say it was payback.

All of these gutsy old guys are above and beyond terrific.

But my favorite is Gideon Lichtman, a former U.S. Army Air Force pilot who shot down an Egyptian Spitfire on June 8, 1948 and went on to fly more than 30 missions during the war.

“I was risking my citizenship and possibly jail time,” he says of fighting for Israel. “I didn’t give a sh*t. I was gonna help the Jews out. I was going to help my people out”.

What Really Happened in 1948? A War in Three Phases

The documentary’s “high-flying chutzpah” focuses on the second phase of the 1948 war, when the Arab states aimed to overrun and cripple the Jewish state and “throw the Jews into the sea”.

But the war in fact began some six months earlier with an Arab attack on a Jewish bus near Lydda Airport on the morning of November 30, 1947—just a few hours after the UN General Assembly passed the resolution to partition Palestine.

During these early months of the war, the Jewish Haganah (it changed its name and became the Israel Defense Forces on June 1) managed to gain battlefield superiority. Still, the Jewish forces endured painful defeats in the effort to keep their lines of communication open—raising significant doubts about the war’s eventual outcome.

On April 6 David Ben-Gurion reported to the Zionist Action Committee that:

Hebrew Jerusalem is partially cut off all the time. For the past 10 days, it has been completely isolated and faces a serious danger of starvation. Almost all other roads are in disarray, Jews cannot set out without risking their lives”.

As we now know, the entire Palestinian force (including the volunteer forces that the Arab League had sent to Palestine in the winter of 1948) was routed in the Haganah’s first major offensives in April and May.

But these early victories were offset by the Arab invasion. Across most of the fighting lines, the Arabs took the initiative at this stage of the war with forces greatly superior to the defending Jewish army.

The war had become, quite literally, a matter of life and death for hundreds of thousands of Jews.

When General Yigal Yadin, the Haganah’s chief of operations was asked by members of Israel’s provisional government about the chances of standing up to the expected Arab attack his reply was a sobering “Fifty, fifty”. Most company commanders at the time also saw this as a grave assessment based on truthful calculations.

Israel was deploying meager forces along strung-out lines utterly vulnerable to the Arab onslaught. The worse defeats of the war took place then—at Gush Etzion, Latrun, Yad Mordechai and many other places.

This sense of vulnerability and weakness was not imagined at this point in time—it was very real.

But in what can only be described as one of the greatest fake-outs in military history, a Jewish American pilot and his buddies flew four “junk airplanes” for a country that had no actual air force, managing to convince the Egyptians, encamped only 30 miles south of Tel Aviv, that there was enough “competition in the sky” to warrant aborting their advance.

There can be no doubt that these volunteers helped turn the tide of the war. It’s a “helluva story”.

In an excellent book on the 1948 war edited by preeminent Israeli historian Benny Morris (who also makes several appearances in the film), Mordechai Bar-On, who served as company commander in the battles against the Egyptians on the southern front, and later against the Iraqis on the central front, describes what might have happened.

Bar-On was ordered to deploy his platoon of some thirty men across the road a few miles north—all they had to face off against the heavy concentration of Egyptian tanks, armored cars, and heavy guns was a few World War II rifles, a few Sten submachine guns, two light machine guns, some antitank mines, one PIAT, and a dozen Molotov cocktails.

As Bar-On recounts:

My mission seemed suicidal…In my mind’s eye, I could clearly see my entire platoon being trampled to death the next morning by the Egyptian column galloping its way to Tel Aviv”.

But the Egyptians decided not to advance north. Because a gang of Jewish Americans were determined to stop them.

In the final phase of the 1948 war Israel again achieved the upper hand. It used the June 11 truce, imposed by the UN Security Council, to its benefit—procuring heavier equipment, including tanks and better airplanes (Schwimmer even managed to buy 3 American Flying Fortress bombers). The IDF was able to replenish its depleted ranks—Holocaust survivors straight from the displaced persons camps helped to build an armored brigade and a few artillery battalions.

But even in these final weeks of the war it was never a cakewalk.

The Egyptian and Iraqi armies engaged the IDF throughout the autumn of 1948 in battles where Jews continued to—rightly—believe that they were the few against the many, in a war between David and Goliath.

Even into early January—just days before the war ended—Iraqi forces mounted a ferocious assault in the Samarian foothills that left the IDF units of the central front outnumbered and outranged in every weapon.

These battles were dicey. The Egyptian and Iraqi enemy fought valiantly, but in the end they had no response to Israel’s superiority in the skies, and it was clear which side had the advantage.

As Bar-On notes:

The ‘miracle’ that helped the 650,000 Jews of Palestine defeat 1.3 million Palestinians and the Arab armies of neighboring states was effected through the Jewish ability to mobilize a superior force and defy the initial demographic imbalance. It was a miracle, indeed, but someone had to perform it.”

The American Jews Who Flew for Israel

Most of the American volunteer pilots featured in “Above and Beyond” survived the 1948 war and went on to lead productive lives in the U.S. and Israel.

Two of the airmen—U.S. Army Air Force pilot Coleman Goldstein and Lou Lenart, a U.S. Marine who served in the Pacific theater during World War II— became pilots for El Al Airlines.

Leon Frankel, a Pacific bomber pilot in World War II who received the Navy Cross for his heroism in the Battle of Okinawa and flew 25 IAF missions, returned to Minnesota.

Harold Livingston, who served in the U.S. Army Air Corps’ transport squadron, became a novelist and a Hollywood screenwriter, authoring Star Trek: the Motion Picture (one of the best films of all time, in my humble opinion).

But two from this courageous band of brothers didn’t make it. Stan Andrews and Bob Vickman—both UCLA art students in 1948 who had been stationed in the Pacific in the U.S. Army Air Force during World War II—were killed when their IAF planes were shot down in separate incidents in July and October 1948.

As told in “Above and Beyond” by the pilots who fought with them, Andrews and Vickman came up with the logo for the 101 Squadron, scribbling the Angel of Death on a cocktail napkin at a Tel Aviv bar in June 1948.

It’s a design that still appears on Israeli F-16s today.

Miriam F. Elman is an associate professor of political science at the Maxwell School of Citizenship & Public Affairs, Syracuse University.

DONATE

DONATE

Donations tax deductible

to the full extent allowed by law.

Comments

Balls of iron. At least three each.

What a wonderful story.

The Israeli pilots called their aircraft Messershitts because of the high maintenance-under-powered engines in the Cezchoslavakian planes. I highly recommend “Above and Beyond.” It’s one heckuva story!

Because the original Daimler-Benz engines were no longer available, the Czech Me-109s had been equipped with Junkers Jumo bomber engines, so yeah, they were beasts to fly. At least the Isaelis managed to get a hold of Spitfires and Mustangs as well.

Excellent writeup. Wonderful read. Thanks!

God Bless and Protect Israel.

Heartwarming – and how things have not changed. Machal-like individuals surely are still among us but, that Ben-Gurion’s words “The Machal forces were the Diaspora’s most important contribution to the state of Israel” might well be inverted, today, to “The State of Israel might be the most important contribution to the Diaspora” is ironic.

Once again, it may be a very close call and, once again, what exactly are we doing for Israel? Whatever it is, though not insignificant, it is grudgingly done and with apologies to the rest of the world. To have fallen so far only seventy short years (this summer) after the end of World War II is disgraceful. God help us all.

And for those of us who prefer the Hollywood version of history there is “Cast a Giant Shadow” with Kirk Douglas.

Happy 67th Birthday, Israel! May you continue to be a shining beacon of freedom and democracy in the darkest corner of our world.

Saw this at a film festival last fall. Don’t miss it.